Alongside nationwide protests, corporations are issuing their own calls for racial justice. With the rise of social media and heightened public consciousness on the issue, they face risks if those words aren't matched by deeds.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

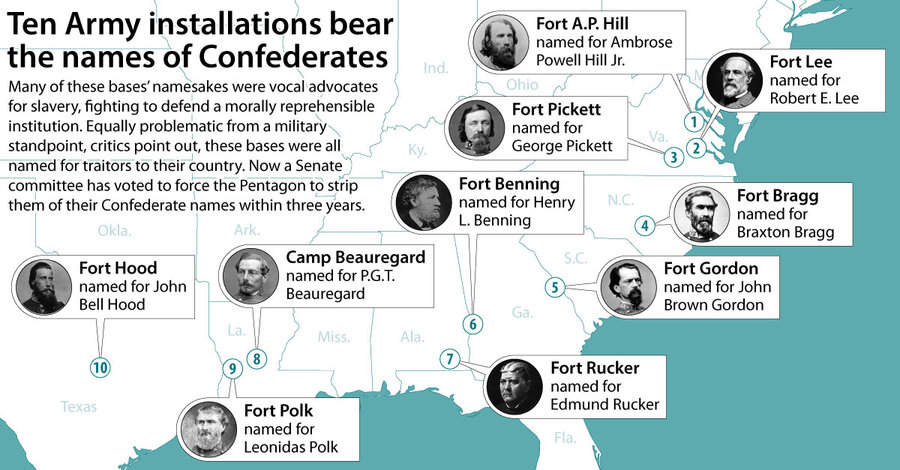

Massachusetts is probably not the first place that comes to mind when you think of the Confederacy.

But when I moved to Walpole in the ’90s, the rebel flag seemed to be just about everywhere – on lawns, vanity plates, and the high school flagpole.

At the time, it was the official school flag.

The school changed it – after much heated debate – my freshman year. It didn’t have anything to do with slavery, many argued. The flag was adopted, along with the team name of the Rebels, all in good fun when coach John Lee turned the football team around in 1968. He became fondly known as General Lee.

But to the few Black students, most of whom were bused into town from neighborhoods of Boston, these symbols felt like a warning – a sign they were not fully welcome.

Although the flag was changed in 1994, the nickname Rebels has endured. Students, graduates, and parents urged the town to drop the moniker . Former Walpole football player Darley Desamot told the crowd the nickname “represents ignorance to a community that has been striving to feel equal.”

When I was in school, some white students seemed genuinely unaware of the symbolism of the flag, the name, or the school song of “Dixie.” A lesson I learned in that moment is resonating once again today as I listen to cries of pain, fear, and frustration coming from my Black American colleagues and neighbors: As historical references become baked into the fabric of our culture, we can be blind to aggressions that may be hidden in the weaving. And so we listen in hopes that we too can start to see.