Do officers belong in schools? Districts cut ties, debate best path to safety.

Loading...

| Austin, Texas

In the wake of George Floyd dying under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer three weeks ago, there is a growing call to reimagine, if not eliminate, policing in the United States – and change is starting in��public schools.

Reversing a decadeslong trend of heightened police presence, a handful of public school districts have gotten rid of their campus police forces in recent weeks, with others taking steps to discuss reductions and changes. The American Federation of Teachers also this week, with the union calling for school safety and policing to be decoupled.

Critics say ending school police programs is an emotions-driven overreaction. When properly trained, they argue, school resource officers (SROs) build positive relationships with students and parents, while protecting schools from outside threats including school shooters.

Why We Wrote This

George Floyd’s death is prompting a rethinking of policing in schools, where students of color are more likely than white counterparts to encounter officers. As partnerships dissolve, authorities ponder how to keep students safe while also treating them fairly.

The back and forth is in many ways a microcosm of the broader societal debate about differences in experiences with law enforcement, often based on race, and whether funding should be routed to counselors and social programs instead.��With the effectiveness of school police programs still relatively unclear, the negatives are now outweighing the positives for some school leaders.

“I don’t know that the marginal costs of [school] policing have changed,” says Emily Owens, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, who studies school police programs.��What’s changed, she says, is that “the marginal costs [are now seen as] so much higher than the perceived marginal benefits that people are finally demanding government leaders do something.”

A cascade of cancellations

Mr. Floyd’s city moved first, with the Minneapolis Public Schools board voting unanimously in early June its SRO contract with the city’s police department. A few days later in Oregon the Portland Public Schools superintendent the discontinuation of the district’s SRO program with the city’s Police Department, which cost the district no money, and his intention to increase spending on counselors and social workers.

Last week the public school systems in ,�����Ի� both voted to end their SRO programs. Their��$300,000 and $750,000 contracts, respectively, with local police departments will be put toward alternative safety programs and mental health resources for students, they said. Next week, the Los Angeles Board of Education phasing out police presence in the nation’s second-largest school district.

While Mr. Floyd’s killing was “a horrible tragedy,” this is one of the last things school systems should be doing, says Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, a nonprofit organization that offers trainings for SROs.��“Schools that do that,” he says, “are losing potentially the best community-based policing they could have.”��

After decades, unclear results��

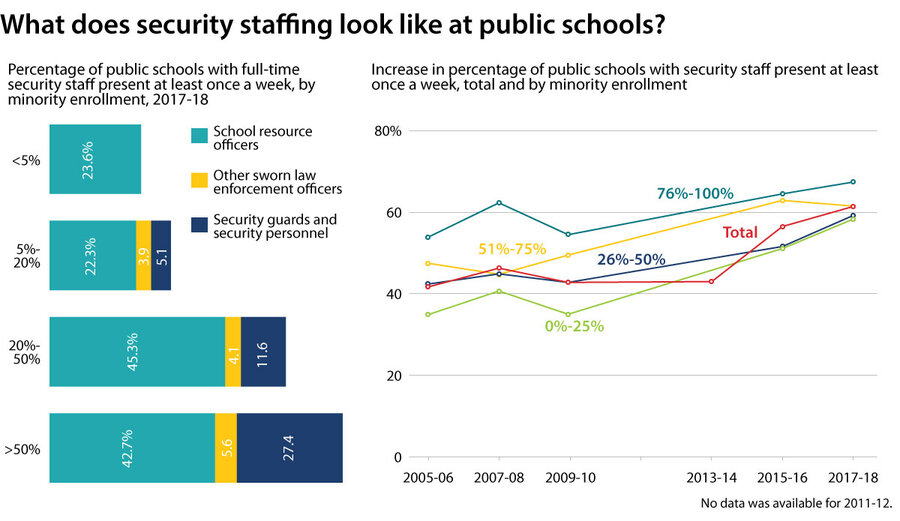

School police officers first began appearing in the 1950s. But beginning in the 1990s – and accelerating after a 1999 mass shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado – police presence has continuously expanded. Roughly half of U.S. students attend a school with an SRO, according to Shawn Bushway, a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corp.

Yet this “dramatic change in social policy,” he says, has continued “without much evidence.”��

“There’s some evidence it decreases serious violence” in schools, he says, “but there’s some evidence it also increases negative outcomes for kids.”

��

A published last month found that SRO or police presence at a school corresponds with an increased probability that student incidents will be reported to law enforcement. Notably, that study failed to find evidence that these consequences disproportionately involve students of color.

Another found that federal grants for school police in Texas increased middle school discipline rates by 6% – driven primarily by low-level offenses and school code of conduct violations, and with Black students experiencing the largest increases in discipline. The study also found that "exposure to a three-year federal grant for school police is associated with a 2.5% decrease in high school graduation rates and a 4% decrease in college enrollment rates."

“Those affects are small, but significant,” says Emily Weisburst, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Los Angeles, who authored the study.��“When students are disciplined, their attachment to school decreases,” she says. “That can translate longer term into a lower likelihood of graduation.”

The benefits of SRO programs are similarly difficult to evaluate.

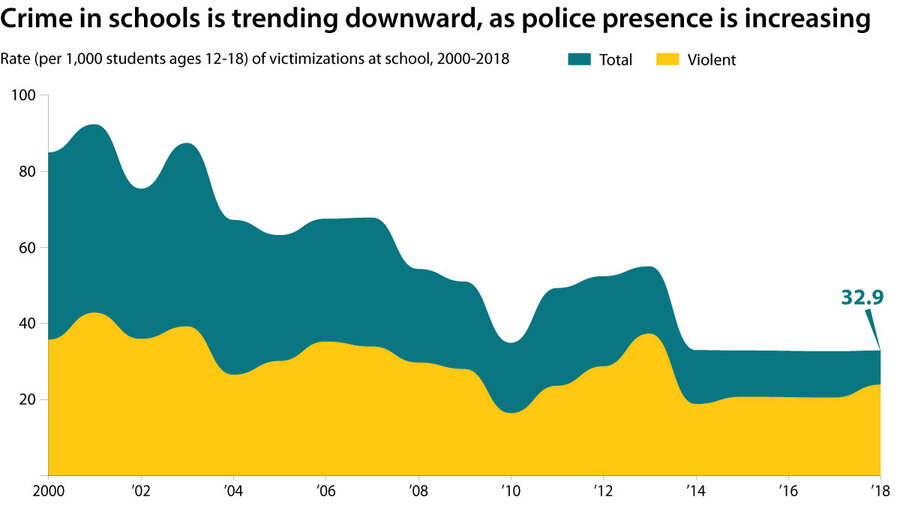

The violent crime rate in schools, and the overall juvenile arrest rate in the U.S., have been declining in recent years – a period that coincides with an increase in schools with campus police officers. Whether there is a correlation between the two is unclear, however. Whether school police build trust and positive relations between law enforcement and students is also, at least empirically, unclear.

��

Meanwhile, some research has found a more fundamental drawback to school police programs.

A Tulane University survey of almost 4,000 New Orleans charter school students during the 2018-19 school year 69% of white students felt safer in the presence of police compared to 40% of Black students. A of thousands of California high school students the year before also found that Black students felt less safe than other students in the presence of police officers, both in and out of school.

“Many well-intended school leaders and school board members erroneously believe that they are making schools safer” with school police programs, says Shaun Harper, executive director of the University of Southern California Race and Equity Center. “That’s not what students say.”

“And if they are in fact so good for the school community, why don’t we see them in predominantly white schools?” he adds.

Momentum in Texas

Police do have a strong presence in predominantly white schools, but they are even more common in predominantly minority schools, statistics show.

In Texas, a coalition of advocacy groups is calling on the public school districts in four major cities in the state to scrap their school police programs.��All four districts have predominantly minority student bodies, and two of the districts, Houston and Dallas, have budgeted more than $18 million and more than $23 million, respectively, for policing and “security and monitoring” services in recent years. All four districts have fallen short in the past two years of the 250-to-1 student-to-counselor ratio recommended by the American School Counselor Association.��

“We’re not just removing police officers, we’re removing police officers and adding the mental health services piece. So [potential] student threats are addressed that way,” says Karmel Willis, an attorney with��Disability Rights Texas, one of the advocacy groups in the coalition.

For alternatives like restorative justice programs to work, research has shown, they need appropriate . But alternatives demonstrate that there is “a different way, a better way, to ensure that there’s justice and accountability and restoration when harm is done in a school that doesn’t require any sort of law enforcement,” says Dr. Harper.

Mr. Canady, from NASRO, says that schools “need more of everything.”��

“Mental health experts aren’t trained on active shooter events. Who’s going to handle that?” he says.��“There are still reasonable conversations to be had about strategies and reform,” he continues. “But that’s difficult to be had when … some people are in an absolute overcorrection mode.”��

The Houston Independent School District had a of 1-to-1,111 in 2018. Still,��decreasing��funding for the policing of schools “would jeopardize the safety of our students and staff,”��the district said in a statement to the Monitor. “The [police] department reflects the demographics of HISD students and families, and the personal relationships that HISD police officers work to cultivate and grow with students are an important component to improving academic outcomes.”��

All eyes on Minneapolis��

For those wanting to pull police out of schools, this current movement is less an overcorrection than a redefinition of school safety. For Andrew Hairston, director of the School-to-Prison Pipeline Project at Texas Appleseed – another advocacy group in the coalition – “It’s encouraging and a little anxiety-inducing.”

“All eyes will be on Minneapolis and Denver and Charlottesville,” he says.

And for school districts that do choose to end school police programs – whether they replace them with more counseling, more mental health resources, restorative justice programs, or other alternatives – it will be a step toward larger change.

“It is trying to build a world that’s never existed, to not rely on the criminal legal system, not rely on police to address social issues,” he says. “It would have to be something that’s invested in wholesale.”