In Iran, assassination shock spurs calls to rethink security

Loading...

| London

Nearly a decade ago, after a string of assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists shook Tehran, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps was assigned the task of guarding them.

The very presence of the powerful IRGC was meant to be deterrent enough to prevent enemy intelligence operatives from further killings, conducted as part of a covert war waged in earnest at the time by Israel and the United States to slow down Iran’s nuclear advances.

“Israel targeted the nuclear scientists because it understood that they did not have the security protection of the IRGC,” Gen. Mohammad Hassan Kazemi, the deputy commander of the IRGC security branch, boastfully announced in late 2013.

Why We Wrote This

Security vigilance is a relentless pursuit that is mentally draining. Did Iran’s yearslong state of alert against Israeli and American infiltration lead to complacency and vulnerabilities?

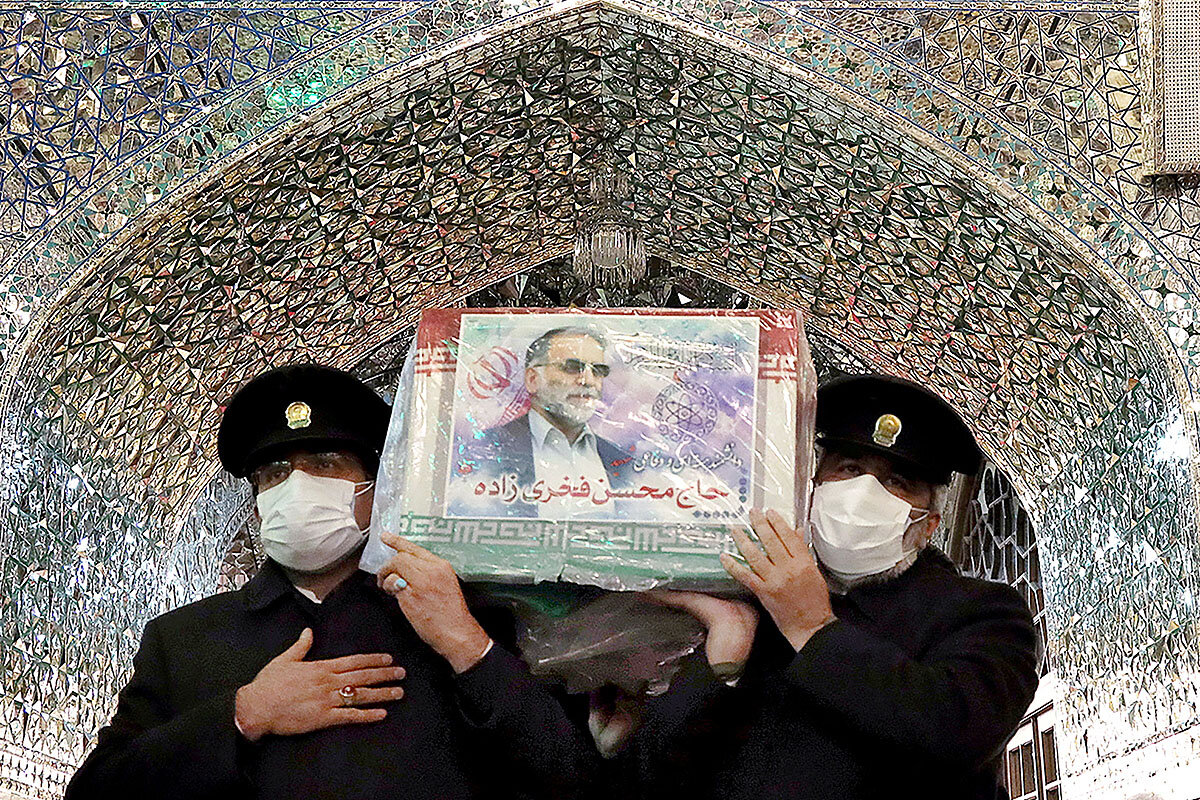

But any claim such a deterrent effect still existed disappeared Nov. 27, when the brazen killing in broad daylight of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh – long reputed to be the “father” of Iran’s nuclear program – exposed deep vulnerabilities in Iran’s security and intelligence apparatus.

The scientist is often described as being in charge of a clandestine weapons effort until it was shelved in 2003. But in 2018 he was mentioned pointedly by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as he presented Iranian nuclear files stolen from a Tehran warehouse that he said proved that aspects of a weapons program headed by Mr. Fakhrizadeh were ongoing. “Remember that name,” he said.

Though close to retirement and using a cover story as an academic – which was used to deny inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) access to him, despite repeated requests – Mr. Fakhrizadeh in fact held the rank of deputy defense minister and was given a dayslong state funeral.

He was a known target, and would have been well protected by the IRGC’s Ansar-ol-Mahdi “secret service” unit. Amid a wave of internal Iranian finger-pointing that has followed the attack, analysts say Iran’s intelligence apparatus often appears to be looking in the wrong places for threats.

“The Fakhrizadeh assassination came as a shock, not because [they] didn’t expect it, but exactly because they did expect and prepare for it, and yet they couldn’t prevent it,” says Maysam Behravesh, an intelligence analyst on contract with Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security from 2008 to 2010, and now a Sweden-based researcher with Clingendael, the Netherlands Institute of International Relations.

“This and past hostile operations could not have been carried out successfully, against all odds, had there not been a complex network of spies and moles deep in Iran’s security structure and intelligence community,” says Mr. Behravesh.

Bodyguards tipped off

The dozen assassins that took part in the ambush of Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s convoy of four armored vehicles melted away after the attack, according to a detailed account posted by Javad Mogouei, a documentary filmmaker who has worked for the IRGC, that was backed up by eyewitnesses and family members quoted by Iranian media.

The hit team deployed a car bomb, a machine gun, assault rifles, and two snipers on a barren rural road near the town of Absard, 40 miles east of Tehran. Officials say Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s bodyguards had been given explicit tipoffs from other Iranian intelligence agencies that they would be hit.

Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei vowed “definite punishment,” but said the first priority was finding and prosecuting the “murderous and brutal mercenaries.”

“Breaches, holes, and infiltrations” led to the assassination, Brig. Gen. Hossein Dehghan, a military adviser to Ayatollah Khamenei and former defense chief, told state TV. General Dehghan, a candidate in Iran’s June 2021 presidential election, called on security officials “to answer as to how such infiltration occurs.”

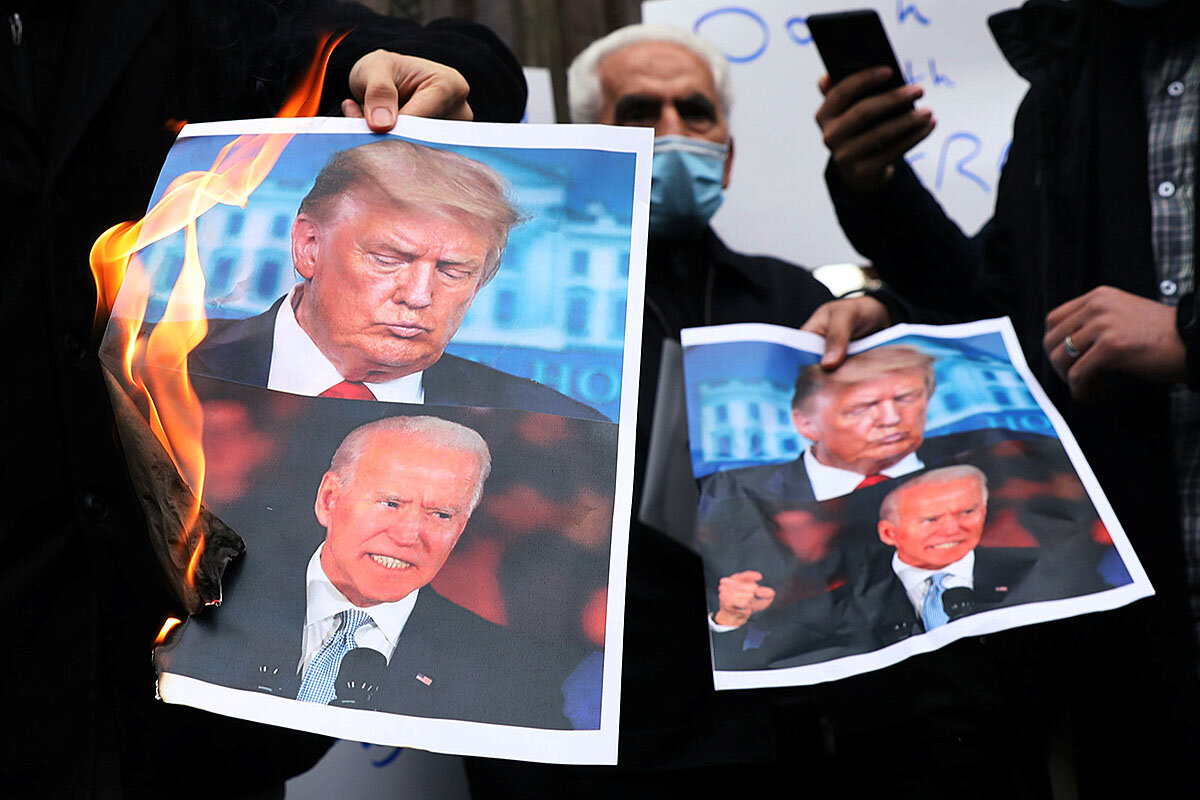

Analysts say the killing of Mr. Fakhrizadeh will complicate efforts by President-elect Joe Biden to resuscitate the landmark, multilateral 2015 Iran nuclear deal. President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA in 2018, in favor of a “maximum pressure” campaign of punishing sanctions.

On Wednesday, Iran’s conservative Guardian Council approved a parliamentary bill requiring the government to boost uranium enrichment and stop IAEA inspections if sanctions aren’t lifted by February. Such a step would remove Iran further from the limits of the deal.

String of breaches

The assassination, meanwhile, is the latest in a chain of security breaches that indicate how agents of Iran’s archfoes, Israel and the U.S., have found ways to penetrate Iran’s intelligence infrastructure and operate relatively freely.

In August, for example, Israeli operatives in Tehran gunned down Al Qaeda’s second-in-command, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, one mastermind of the 1998 attacks on U.S. embassies in Africa, “at the behest of the United States,” The New York Times .

In July, amid a summer of unexplained explosions across Iran, a mysterious fire damaged Iran’s uranium enrichment facility at Natanz. Officials attributed it to “sabotage.”

This past January, a U.S. drone killed the commander of Iran’s IRGC Qods Force, Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, in Baghdad.

The latest killing “is expected to prompt some serious soul-searching within the leadership as the enemy is apparently ‘closer to them than their necks’ veins,’ as some in Tehran like to put it,” says Mr. Behravesh.

Iran blames Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency, which has a decadeslong history of conducting targeted assassinations across the Middle East and beyond. Israel has not denied a role, nor sought to dispel the sense that it operates with impunity in the Islamic Republic.

“The truth of the matter is that there are people inside the regime that are likely leaking this information,” says Afshon Ostovar, an Iran expert at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California.

“They’ve got a leaky ship, and I think that’s the scariest issue for them, because there’s no clean way to deal with that. It’s going to be messy,” says Dr. Ostovar, author of “Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards.”

“If Israel really is behind all of these assassinations over the years, they’ve obviously got it down pretty well,” says Dr. Ostovar. “But when you combine this with the Al Qaeda assassination, with the stealing of the nuclear documents ... it’s kind of like Iran is going to school every day and doesn’t know when the bully is going to take its lunch money.

“I don’t know if that is how the Islamic Republic sees it. But if I’m in the security forces I’m really frustrated, because this stuff is just not being prevented,” he says.

A specific alert

Ali Shamkhani, chief of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, told state TV that Iran’s intelligence agencies had “precisely predicted” the attack and its location, and the scientist’s security had been boosted. But “due to the frequency of reports [about attacks on him] over a 20-year period, precautions were unfortunately not observed, and the enemy succeeded this time,” he said.

Government spokesman Ali Rabiei went further, saying the Ministry of Intelligence had collected specific details about the pending attack and shared them as a “terror operation alert” with the security organ in charge.

“They could have made the crime fail if they had been a bit careful and followed the security protocols,” Mr. Rabiei told a virtual news briefing.

The backlash has been fierce, with groups of protesters – most of them hard-liners – gathering outside the president’s office, Foreign Ministry, and Parliament, demanding revenge and calling on Iran to spurn the nuclear deal.

For Iran, with its “powerful system equipped with thousands of skilled [intelligence] forces, a security breach is not acceptable,” wrote the hard-line newspaper Kayhan, noting that producing someone of “super-strategic importance” like Mr. Fakhrizadeh was a 50-year project.

“There is no chance we can look the other way in the face of mistakes and failures that have been committed with regard to infiltration,” Kayhan wrote.

Looking at the wrong targets

But looking in the wrong direction may be part of the problem, says Dr. Ostovar. IRGC intelligence has invested heavily in rooting out “infiltrators,” but for years pulled in dual-citizen academics and journalists.

“They’re just spending time on the wrong targets,” he says. “What gets in their way, probably more than anything, is that they really misunderstand the adversary. When they arrest [journalists] like Jason Rezaian and Maziar Bahari, they legitimately thought these guys were part of some spy network.”

“They really are paranoid, the IRGC in particular,” adds Dr. Ostovar. “You wonder if the omnipresence of the threat that they perceive actually obscures the threat in their midst. They only see the forest; they don’t see the trees.”

In the most recent example, a Swedish Iranian disaster medicine scholar, Ahmadreza Djalali, reportedly faces execution this week. He was arrested in 2016 after being invited to a conference in Tehran, then sentenced to death in 2017 on charges of spying for Israel. A group of 153 Nobel laureates signed a letter calling for his release.

Meanwhile, on the ground in Iran, actual foreign operatives appear to work with few limits.

“It’s been just like American action movies,” wrote Mr. Mogouei, the pro-regime filmmaker. “The whole file tells us that the intelligence apparatus has suffered serious holes for years, very deep ones. We need to drive back and cleanse the system.”