Party of one: Why record numbers of Americans are going it alone

Loading...

| New York

When Hilary Reiter left New York City 20 years ago and moved to Park City, Utah, she didnβÄôt think she would still be single two decades after moving out West.

Even as the number of single adults across the country continues to reach unprecedented levels, Ms. Reiter says she never made a βÄ€proactive decisionβÄù to forgo marriage and live alone. In some ways, sheβÄôs remained unattached into her 40s due to happenstance.

βÄ€But I also think thereβÄôs more to it than that,βÄù says Ms. Reiter, who has never lived with a romantic partner. βÄ€I was never one of those girls who wanted the 300-person wedding and white wedding dress. I am staunchly independent, and maybe one of my weaknesses is my inability to compromise. I like having my own space; I like being able to come and go as I please and not have to accommodate somebody else.βÄù

Why We Wrote This

Laws, finances, employment, even dinner parties are still stacked in favor of couples, but nearly half the adult U.S. population is now single. And more of them say they are tired of being told to pair up to fulfill their pursuit of happiness.

βÄ€I guess I also like not having any drama,βÄù she says. βÄ€I feel like so many of my relationships were just dramatic and full of heartbreak. Some of them were pretty toxic.βÄù

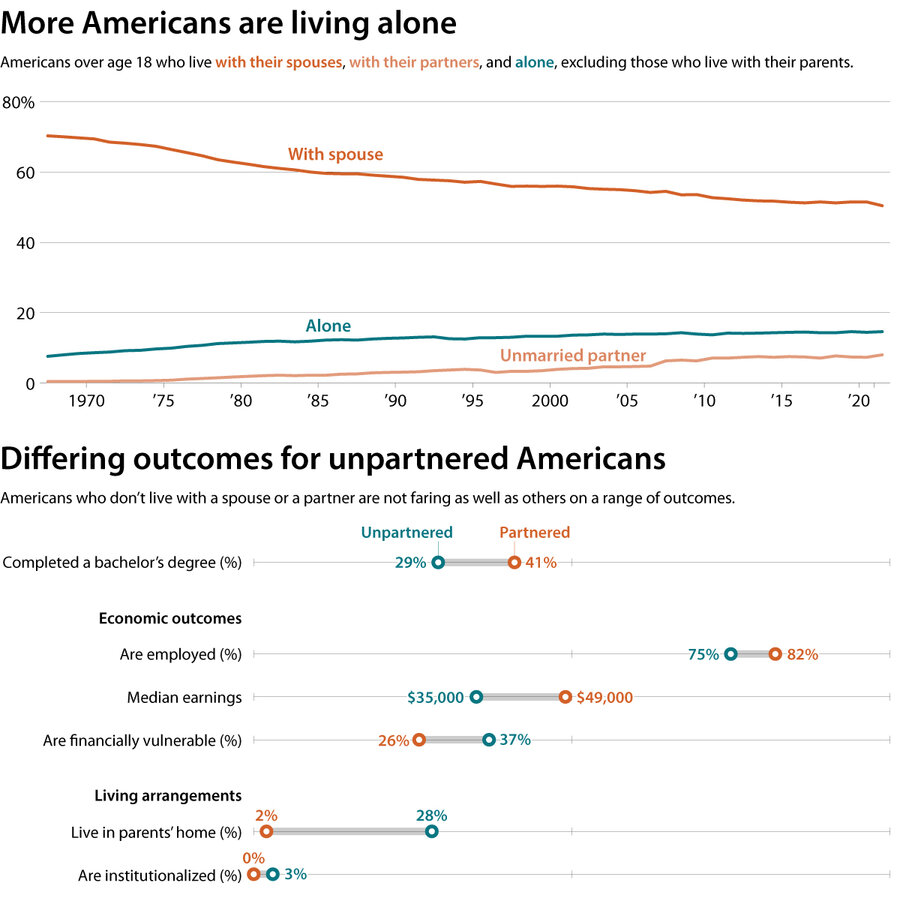

The number of single adults in the U.S. has been rising steadily since the 1950s, researchers say, when about 1 out of 4 adults were unmarried βÄ™ and many were single men who migrated west to work in places like Alaska. Back then, as for most of human history, there remained a deep-seated social expectation that after coming of age, most full-functioning adults would find a vocation, get married, and start a family.¬†¬†

Today, however, nearly half the adult population is single βÄ™ about 128 million Americans. This demographically diverse and socially mixed group includes people at different stages of their lives, as well as single parents, LGBTQ individuals, romantic partners who cohabitate, and those simply waiting longer to find the right person.¬†

Yet more and more people are finding that they may just prefer living solo βÄ™ even if they also feel the weight of a society whose social rituals and legal traditions have been built around a world expecting couples and the families they start.¬†

In 2020, nearly 4 out of 10 adults between ages 25 and 54 were neither married nor living with a partner βÄ™ a 30% increase since 1990, according to a recent Pew Research Center . More significantly, the number of single-person households in the U.S. has doubled from 18.2 million in 1980 to 36.1 million today, or about 28% of the nationβÄôs total, . An additionalhomes are headed by a single parent, the number in 1965.

βÄ€There are few truly revolutionary transformations in the way that we live as human beings, and this is one of them,βÄù says Eric Klinenberg, a noted social thinker at New York University and the author of βÄ€Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone.βÄù¬†

βÄ€ItβÄôs βĉextraordinaryβÄô because in the history of our species until the middle of the 20th century, there was never a society that sustained large numbers of people living alone for long periods of time,βÄù he says.

When she was in her 20s Ms. Reiter was living in ManhattanβÄôs Lower East Side, working in the music industry and just beginning her career in public relations. After 9/11, however, she had an opportunity to work three months for the Sundance Film Festival.

βÄ€I figured, OK, IβÄôll go to Utah for three months, IβÄôll experience the glitter of Sundance, IβÄôll ski my heart out, and then IβÄôll go back,βÄù Ms. Reiter says. βÄ€But then I never went back. The quality of life here was just too good.βÄù¬†

Although there were far more single men than women in Park City, most were involved in the cityβÄôs ski and tourism industry, she says, and few attracted her in a deep way.

She found that living alone simply suits her βÄ™ even if she hasnβÄôt ruled out the possibility of meeting someone, someday. Still, one of the biggest drawbacks, she says, is the not-so-subtle social stigma surrounding being single at her age, especially since sheβÄôs a woman.

βÄ€Sometimes you donβÄôt get invited to certain gatherings because you donβÄôt have a significant other, and I think people feel βÄ™ I donβÄôt know, they ask questions like, βĉAre you dating anyone?βÄô And if youβÄôre not, βĉWhy arenβÄôt you dating anybody?βÄôβÄù says Ms. Reiter, who in 2010 launched her own marketing and public relations firm in Park City.¬†

βÄ€Now I kind of feel compelled to correct some of the myths out there that, you know, single people are miserable and that weβÄôre unfulfilled in our lives,βÄù she says. βÄ€Some of us are very satisfied being single and would kind of like to set the record straight on that.βÄù

Dr. Klinenberg, too, expected to find groups of isolated, lonely, and depressed people when he first began to study the steady rise of single adults over two decades ago. βÄ€The general conversation about people living alone at the time was that it was an alarming sign of social atomization, or that there must be something wrong with people who lived alone,βÄù he says.

βÄ€So I thought I was going to be writing a book about an emerging social problem,βÄù Dr. Klinenberg continues. βÄ€Instead, what I found was that the majority of the people were actually in pretty good shape and pretty content, and that was surprising to me.βÄù

The reasons for this transformation are in many ways rooted in the revolutionary changes of the modern world. The growing affluence of postwar Western societies made living single a viable possibility for more people, even as modern social support systems began to bolster rising household incomes. At the same time, waves of revolutions in communications technologies allowed people to connect in dramatically different ways than before.

One revolutionary transformation driven by the rise of singles, in fact, has been the revitalization of urban life. As younger Americans embraced city living, they in many ways wanted to live alone, together, Dr. Klinenberg says, and spend a lot of time and money in public spaces. Conversely, with so many public social connections, including those online, living alone affords a kind of βÄ€restorative solitude.βÄù¬†

βÄ€ThereβÄôs many reasons for the rise of solos, but the number one reason is probably the rise of women, both economically and educationally,βÄù says Peter McGraw, a behavioral economist at the University of Colorado Boulder. βÄ€Once women are given an alternative path to survive and thrive economically, many of them are going to opt out of the patriarchy. Suddenly getting married and having kids is an option, not the default.βÄù

Brigette Eaton felt for a long time that she didnβÄôt have many options outside her communityβÄôs expectation that she should marry and start a family.¬†

Raised in the traditions of conservative Black Protestantism in Baltimore, Ms. Eaton says she married in 2011 mostly out of religious obligation. She never wanted to have children, βÄ€and I never even looked at marriage as a financially beneficial thing. I just looked at it, as you know, essentially what you do in order to not be in sin.

βÄ€I mean, I really love my ex-husband. We were good friends,βÄù says Ms. Eaton, who divorced in 2014. βÄ€ItβÄôs just that we wanted totally different things in life. It just didnβÄôt feel right, you know, as they say, feeling right about something in the spirit.βÄù

She wanted to live in the city, and she is committed to her career as a crisis counselor, now in the process of getting her Ph.D. After launching her own private practice two years ago, sheβÄôs become a lot more financially independent. Since the pandemic, too, Ms. Eaton says she doesnβÄôt feel a deep need for physical intimacy.

SheβÄôs only now starting to find a way to conceive and embrace what now feels like her natural state. As a person of deep faith, Ms. Eaton finds comfort in a passage in I Corinthians, where the Apostle Paul tells those unmarried or widowed that it is better to remain unmarried, like he is.

But she also came across the work of Dr. McGraw, who is building a community through his , βÄ€Solo: The Single PersonβÄôs Guide to a Remarkable Life.βÄù

After listening to an episode about attachment styles, Ms. Eaton had a sudden realization after she scored as an βÄ€avoidantβÄù in relationships: βÄ€I just want to be single,βÄù Ms. Eaton says. βÄ€And then whatβÄôs funny is, I feel, now I donβÄôt feel alone.βÄù

Dr. McGraw began to study the rising number of single people for deeply personal reasons, he says. A lifelong bachelor in his 50s, he says he had struggled his whole life with being single, experiencing heartbreak and broken engagements along the way.

βÄ€I thought, βĉWhat is wrong with me?βÄôβÄù he says. βÄ€You feel guilty for not wanting this thing that IβÄôm supposed to want, and now IβÄôm hurting this person who is being perfectly reasonable about what she wants.βÄù

βÄ€I like dating. I like having relationships,βÄù he says. βÄ€But I was very slow to recognize that thereβÄôs a way to be single like that with integrity.βÄù

In his podcast, he often discusses how people can βÄ€get off the relationship escalatorβÄù and instead focus on developing deep friendships and meaningful connections, putting aside the assumption that every romantic encounter should, or could, escalate to a potentially lifelong partnership.

In one recent episode, he and his guests analyze βÄ€The Golden Girls,βÄù discussing how single people are experimenting with housing and re-envisioning living spaces in ways beyond traditional roommates. One guest purchased a five-bedroom house and was remodeling it to include a bathroom in every room.

Social psychologist Bella DePaulo helped pioneer the study of single people with her 2007 book, βÄ€Singled Out. How Singles Are Stereotyped, Stigmatized, and Ignored, and Still Live Happily Ever After.βÄù

There remain a number of significant structural obstacles, says Dr. DePaulo.

Much of her work has detailed what she calls βÄ€singlism,βÄù including various employment practices, tax perks, and and social traditions that benefit married couples.

She had already established herself as an expert in the psychology of lying and detecting lies in the mid-1990s when she started talking to some of her single colleagues about the slights they often faced, such as being asked to cover courses in time slots married faculty didnβÄôt want, or when coupled friends βÄ€demotedβÄù invitations to lunch instead of dinner.

βÄ€The informal slights were already bad enough,βÄù Dr. DePaulo says. βÄ€As a single person, I was being treated as though I was not fully adult, as if my time and even my life just wasnβÄôt as important or as valuable as married peopleβÄôs. In my conversations, I found that other people were feeling the same way.βÄù

In many ways, advocates for single people follow the same road maps as a generation of LGBTQ advocates: Why canβÄôt good friends share the advantages of couples when it comes to health care plans, filing taxes jointly, or designating each other as beneficiaries for benefits such as Social Security?¬†

She often cites former Supreme Court Justice Anthony KennedyβÄôs in Obergefell v. Hodges, legalizing same-sex marriage: βÄ€Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there.βÄù

βÄ€What Justice Kennedy said was so stigmatizing of single people and single life,βÄù she says. And while she fully supports marriage equality, βÄ€I want single people, regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation, to be included in the progress that is made.βÄù¬†

Those who are single, in fact, to the civic life of their communities, Dr. DePaulo and others have found.

When Robert Trout was going through a heartbreaking if amicable divorce over a year ago, he says he was feeling both disoriented and lost, envisioning a socially isolated future as a man his age now divorced and single.

βÄ€I was devastated, to be perfectly honest,βÄù he says. βÄ€I wanted a life with my wife and child. I wanted that dream.βÄù

βÄ€I had all this stuff come up: Shame about failing, experiencing grief, all of it in the forefront emotionally,βÄù says Mr. Trout, the founder of the Experiential Healing Institute in Paonia, Colorado, which helps parents navigate the needs of children with addiction or behavioral issues.

Then he found Dr. McGrawβÄôs podcast. He was skeptical it might be just another self-help offering. But just having a model for a different kind of life, he says, completely transformed how he understood himself.¬†

βÄ€Just through the process of listening, I felt not alone βÄ™ which is the great irony of the name: βĉSolo,βÄôβÄù Mr. Trout says.

Mr. Trout drove five hours to Denver to attend Dr. McGrawβÄôs βÄ€Solo Salon.βÄù HeβÄôs taken small tips to heart, like having clothes tailored or trying new experiences. And now heβÄôs also meeting his neighbors more, planning projects at home, and engaging in civic activities he hadnβÄôt even considered before.¬†

Ms. Eaton, too, has consciously cultivated deep friendships. βÄ€I can truly say that the friends I have now God has definitely placed in my life. ... They can give me, you know, as the saying goes, βĉreproof in love.βÄôβÄù

SheβÄôs also organizing local face-to-face meetups via online apps, putting together virtual book clubs, and organizing events such as outdoor backpacking for beginners.¬†

But not every solo is what Dr. DePaulo calls βÄ€single at heart.βÄù Dr. McGraw lays out four categories he's generally found: βÄ€SomedaysβÄù think itβÄôs important to find a lifelong partner; βÄ€Just MaysβÄù still think they might find someone, but they wouldnβÄôt feel regret if they didnβÄôt. βÄ€No WaysβÄù are those not looking at all, and βÄ€New WaysβÄù are interested in romantic relationships, but not a traditional one.

Mr. Trout falls into that final category. βÄ€At my deepest desire, I want to fall in love,βÄù says Mr. Trout. βÄ€But what that means is different than it used to mean. I used to think of that as, oh, get married, have kids, get the house, the job, the money. Potentially, I would find someone that, maybe we live in separate households, but weβÄôre together. We are supporting each other, weβÄôre traveling together. We are in love.βÄù¬†

There are significant drawbacks for those wishing to remain single. It often requires a higher level of affluence and social status, since one of the primary benefits of living as a couple are traditional economies of scale.

βÄ€And there is a whole generation of single people now who are Gen Xers or older millennials, and whatβÄôs going to happen to us when weβÄôre old and we donβÄôt have children to take care of us?βÄù says Ms. Reiter. βÄ€We donβÄôt have a spouse to take care of us, or that can give us a sense of purpose as we take care of them. Some of us joke, weβÄôre probably going to have to have these single-women dormitories when weβÄôre in our 80s and 90s, or borrow our nieces and nephews often to take care of us.βÄù

Dr. McGraw, too, notes that the rise in singles across the country includes lower-income men βÄ™ many of whom are not single by choice, who are starting to be left behind both socially and economically βÄ™ a trend also noted in the Pew study.

βÄ€When you have young men who are adrift, without purpose and without connection, consuming too much pornography and playing too many video games, that is bad,βÄù he says.

βÄ€I was involuntarily celibate in my 20s because I just had no skills,βÄù he says. βÄ€So some of these men will improve and compete and figure it out. But then the worry is, the guys who donβÄôt will be the ones who become misogynistic, angry, bitter, and blame women for their situation in life.βÄù

After decades of advocating for those who are βÄ€single at heart,βÄù Dr. DePaulo is starting to see the cultural needle move as single people become more visible and vocal about their needs.¬†

βÄ€They are the people who live their best lives βÄ™ their most meaningful, fulfilling, and authentic lives βÄ™ by living single,βÄù she says. βÄ€Many of them spent a long time trying to force themselves onto the path of romantic coupling, because they never heard of such a thing as living your best life by living single. ThatβÄôs not fair to them. It is also not fair to their romantic partners, who deserve to be with people whose best lives are coupled lives.βÄù