Pulling punchlines: Comedy can be offensive. But should it be reined in?

Loading...

| Boston and New York

Stand-up comic Dan Crohn is telling a joke about the first time he flew Spirit Airlines. It’s Comedy Tuesday at Night Shift Brewing in Everett, Massachusetts. Standing on a spotlit stage, Mr. Crohn forms a wishbone with his arms – elbows lifted high and hands pressed together – as he holds the microphone.

“Imagine the Maury Povich show at 31,000 feet,” riffs the comedian. “The flight attendant comes up to me, and she’s like, ‘Got any food?’”

Mr. Crohn’s subject matter is fairly innocuous. Well, apart from an oceanic joke about cuttlefish having sex, which is probably a first in the annals of comedy. Nonetheless, in an interview prior to the show, he says comedians are suddenly hyperaware of getting in trouble for saying the wrong thing. On the same day, nearly 3,000 miles away, a small group of Netflix employees staged a high-profile walkout at the streaming service’s Los Angeles headquarters. They were protesting Dave Chappelle’s latest comedy special, “The Closer,” for its subject matter about transgender people. It’s a third-rail topic.

Why We Wrote This

Comedy often causes offense. But it can also be a uniter, helping us see a fresh perspective. As cancel culture sweeps the United States, often targeting comedians, the question looms: Is it protecting people from harmful laugh lines or stifling a valuable form of expression?

“I had a joke in before where I said, ‘Do you think transgender fetuses should get angry at gender-reveal parties?’” says Mr. Crohn, who has appeared on NBC’s “Last Comic Standing.”

“And I go, ‘Guys, that’s not offensive. That’s pro-transgender, pro-fetus, and pro-parties.’ But I haven’t done it in a while.”

Is it safe to laugh anymore? There’s long been a tradition in comedy of joking about taboo topics. But in recent years, comedians have either embraced or run away from making light of gender, race, and the #MeToo movement. They’re very conscious of the occupational hazards. Famous people and ordinary citizens alike have been fired from jobs, stripped of opportunities, and banished to a social-pariah wilderness for transgressing new language conventions or for expressing heterodox views. There’s some argument about just how widespread cancel culture is and whether it’s predominantly a left-wing phenomenon. But there have been sufficient examples that many people now self-censor what they say or write no matter what the political tilt of the topic.

For many comedians, freedom of expression is a fundamental value. That’s why John Cleese, Bill Maher, David Spade, Bill Burr, Ricky Gervais, and Mr. Chappelle complain that so-called wokeness has a chilling effect on comedy and societal customs. In response, critics counter that their jokes are sometimes unnecessarily cruel, are in poor taste, or even have a dangerous influence on how people think and act. They worry that these laugh merchants are undermining efforts toward social progress and the protection of marginalized groups.

A lot of comedy causes offense. (Spare a thought for all the cuttlefish out there.) Comedy may be the closest thing society has to a Rorschach test – what people can, or should, tolerate. We often don’t know where the ever-shifting boundaries are until comedians venture out to test the edge. These days, there’s a greater risk of toppling over it. If a new Puritanism is sweeping the nation, the comedy club or Netflix special may be the place where the new cultural arbiters in their knee breeches and petticoats are being the most vociferous.

Yet humor can also be a uniter. It can help us see something from a fresh perspective, making us laugh in acknowledgment of the illumined truth. Jokes often reveal that even those wholly unlike ourselves share common experiences, reminding us that maybe we’re not that different after all. Amid the push and pull of cancel culture versus free speech, is it possible for high-toned humor to facilitate mutual respect based on recognizing our shared humanity?

“Comedians are sort of battling with what they can say, what they can get away with,” says Omotayo Banjo, an associate professor of communication at the University of Cincinnati, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Mr. Chappelle and how audiences react to racial humor. “I think it is a healthy moment. I think we really need to figure out – and I don’t know that we really will – but I think it’s still good to have the conversation of what is acceptable, what is not acceptable, and why not.”

Peter McGraw isn't a comedian, but his job entails making people laugh and then observing them when they do. As the director of the Humor Research Lab, he along with his colleagues is trying to answer a 2,500-year-old question: What makes things funny?

More specifically, Dr. McGraw and his colleagues are trying to understand when and why people laugh about situations that involve tragic circumstances, inappropriate situations, and immoral behavior.

“This is something that Plato and Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, Thomas Hobbes, Sigmund Freud each puzzled over,” says Dr. McGraw, professor of marketing and psychology at the University of Colorado Boulder. “We just had a tool that was unavailable to them, and that is the experiment.”

The Humor Research Lab sounds like something out of a Monty Python sketch. It conjures up images of scientists in white coats who make notes on clipboards when unsuspecting human guinea pigs sit down on whoopee cushions. The research team does appear to have a sardonic sense of humor – the lab’s acronym is HuRL. And the researchers’ work is pretty sophisticated. In a series of studies, HuRL found that its subjects often laughed at potentially benign moral violations. Yet malign moral violations tended to elicit negative reactions. Joke writers have to navigate between those poles.

“You’ve got these two levers you can pull, right? Make it more benign; make it more of a violation,” says Dr. McGraw. “That’s hard to do. You have to have some natural talent. You’ve got to be smart. But you also have to be an empiricist.”

Indeed, some jokes rely on discomfort in the setup as the stand-ups venture into embarrassing or disquieting territory, explains Kliph Nesteroff, author of “The Comedians,” an encyclopedic history of comedy. Comics get a laugh when they release the tension with a punchline, especially if it takes the listener by surprise.

In the pursuit of the biggest laugh, edgy humorists test the boundaries of subjects and conversations that are taboo. Some of them consist of topics you’re supposed to avoid over a Thanksgiving dinner: sex, politics, religion, mothers-in-law.

“Theories of humor suggest that we enjoy humor when we’re not the target,” says Dr. Banjo of the University of Cincinnati. “It’s always easier to laugh at other people, but when our group is the target, we become a little more defensive.”

In “The Closer,” Mr. Chappelle takes on transgender people (as well as many other groups). At times, the comic appears to side with the LGBTQ community by railing against the bathroom bill in North Carolina, which required transgender people to use facilities that corresponded to the sex on their birth certificates. He also tells a heartfelt story about his friendship with a transgender woman named Daphne Dorman, who died by suicide. His comedy special on Netflix is a critique of the hierarchy of victimhood. Mr. Chappelle’s contention is that some people appear to get more upset about transgender issues than they do about racism.

“He draws a kind of proverbial line in the sand against Black people and Black communities and queer communities. That line in the sand has massive erasure for Black queer folks,” says Brandon Manning, an assistant professor of Black literature and culture at Texas ���Ǵ��� University in Fort Worth. “Even his ability to bring in Daphne Dorman towards the end, in many ways that’s the equivalent of saying, ‘I have a Black friend, so I can’t be racist.’”

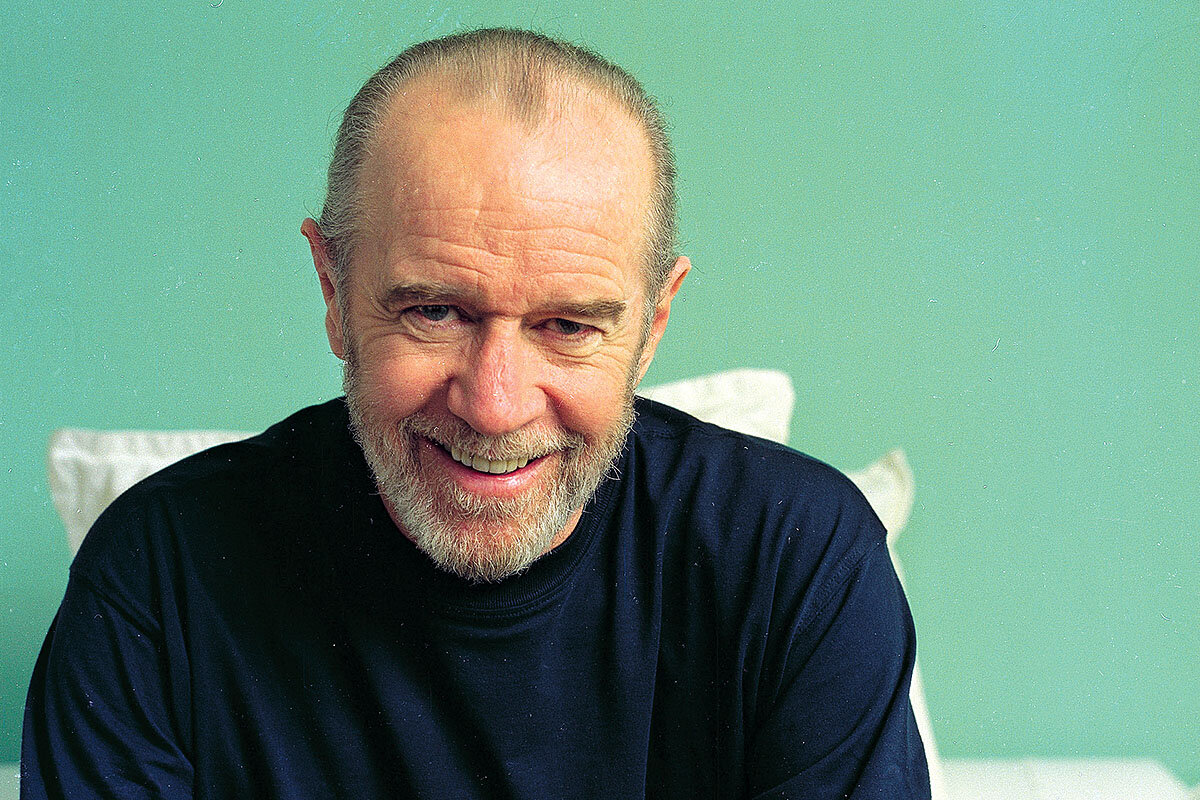

In trying to illustrate his claim that nothing should be off-limits when it comes to humor, Mr. Chappelle also makes merciless fun of the physique and pronouns of transgender people. Indeed, he seems to be following the maxim of George Carlin: “It’s the duty of the comedian to find out where the line is drawn and cross it deliberately.”

But the line of what’s socially acceptable keeps shifting.

Protests of comedy shows date back at least to the early 1900s. Wayne Federman, author of “The History of Stand-Up,” recalls Roman Catholic organizations in the Midwest in 1905 being upset over vaudeville performers who trafficked in stereotypes about the Irish and drinking.

These days, those types of jokes are frowned upon, especially if the humorist isn’t a member of that group. It’s an example of how humor has always had to adapt to changing standards in society even if, at times, it’s slower than some might wish.

At the time of those Catholic protests, stand-up was a relatively new art form in the United States, which pioneered the genre. The first comic, Charles F. Browne, hit the lecture circuit in 1861 and adopted the pseudonymous persona of a country yokel named Artemus Ward. (Think a 19th-century Larry the Cable Guy, or perhaps we should say Larry the Telegraph Guy.) Mark Twain and others soon followed. Ethnic and immigrant stereotypes were a comedy staple in vaudeville shows.

Blackface also got its start in minstrel shows in the late 1800s. It persisted as a tool of comedy until the early years of the millennium. In 2020, Jimmy Fallon apologized for inappropriate use of shoe polish on his face two decades ago on “Saturday Night Live.” Tina Fey withdrew four episodes of “30 Rock” from circulation because various characters had worn blackface.

In the early 1960s, Lenny Bruce was arrested several times, ostensibly for obscene language. But Mr. Federman, who is filming a documentary for HBO about Mr. Carlin, speculates the real reason was that “he was a Jewish guy attacking religion.”

By the last few decades of the 20th century, the seven words that Mr. Carlin observed you couldn’t say on television had become common in clubs and on subscription cable channels. When Andrew Dice Clay made history in 1990 by selling out two nights at New York’s Madison Square Garden, he famously recited vulgar nursery rhymes that would have made Mother Goose lay an egg. Yet Mr. Clay’s sexist and homophobic material had become so controversial that Hollywood studios wouldn’t go near him. Protesters gathered outside his shows. By 1995, even Mr. Clay opined that he’d taken his sexist alter ego persona too far and changed his act. A year later, Eddie Murphy similarly apologized for his gags about gay people and HIV in his 1987 hit stand-up comedy film, “Eddie Murphy Raw.”

Those atonements arrived during another cultural shift – one that began to play out not just on comedy stages but also on TV.

“Over the course of the ’90s this kind of popular understanding of what political correctness is, is developing,” says Philip Scepanski, author of “Tragedy Plus Time: National Trauma and Television Comedy.” “Then ‘South Park’ and ‘Family Guy’ premiered by the late ’90s and really make up an art form of being anti-PC.”

In the 1990s, that tension between those in favor of political correctness and those who chafe at speech codes played out as skirmishes. In the early millennium, it developed into a full-blown culture war. Some comedians are still very much on the front lines, lobbing jokes from the trenches.

Allison Gill used to feature jokes about rape in her stand-up routines. Dr. Gill is a survivor of sexual assault from her time in the Navy. (She appeared in “The Invisible War,” an Oscar-nominated 2012 documentary about rape in the U.S. military.)

“A lot of my humor was around rape and rape culture,” says Dr. Gill, whose comedy special “Benefits of a Misspent Youth” was released in 2017. “And that helped me. It was sort of an exposure therapy, right? Talk about what had happened to me, but in a humorous way.”

But she no longer includes some quips about the issue in her comedy. She discovered that the irony was getting lost on audience members. It’s often a generational thing. Many observers say that millennials and Gen Zers don’t respond well to irony and satire anymore. “They’re very literal and straightforward,” says Dr. Gill, adding that they want you to say exactly what you mean because otherwise it can be interpreted as a microaggression.

Younger audiences not only eschew archness in comedy but also see humor as a kind of therapeutic exercise that’s more personal, more rooted in pain. Comedy specials such as Hannah Gadsby’s “Nanette,” Bo Burnham’s “Inside,” and James Acaster’s “Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999” explore mental health issues in a delivery that’s highly confessional and often completely serious.

“I’d argue that a younger millennial or younger Gen Z generation has made comedy and the stand-up stage a site of wellness and vulnerability,” says Dr. Manning from Texas ���Ǵ��� University. “They’re able to create humor in a way that doesn’t laugh at their pain.”

Some millennials and Gen Zers are leery of comedy that makes light of victimhood and identity – in their eyes, Mr. Chappelle’s “The Closer” probably constitutes a macroaggression. They worry that style of comedy diminishes the struggles of marginalized groups. Some believe words that cause emotional discomfort are dangerous.

That’s why so many colleges that hire comedians these days contractually stipulate what they can’t say onstage. In response, comedians such as Jerry Seinfeld and Chris Rock have said they will no longer play campuses. Having to preface each joke with a warning label does tend to put a crimp in a stand-up routine. But confining comedy to subjects that don’t make people feel unsafe isn’t just limited to college auditoriums – it’s permeated society.

An offensive joke, captured on a tweet or a cellphone camera or TV special, can lead to a headline-making furor. Sometimes protesters claim that such humor endangers marginalized groups by dehumanizing them and inviting physical attacks. The case for safety, and concern about ridicule, were invoked by some – including members of GLAAD (formerly the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) – who urged Netflix to yank “The Closer” from its platform.

In response, Netflix co-Chief Executive Officer Ted Sarandos wrote, “Violence on screens has grown hugely over the last thirty years, especially with first party shooter games, and yet violent crime has fallen significantly in many countries. Adults can watch violence, assault and abuse – or enjoy shocking stand-up comedy – without it causing them to harm others.”

Despite the blowback, Netflix hasn’t removed “The Closer.” On Rotten Tomatoes, a website that aggregates reviews, media critics gave the special a paltry 44% rating. Yet the audience score is 95%.

Mr. Chappelle’s popularity means that he can still command large crowds at shows. But he claims that film festivals have withdrawn invitations for him to screen his upcoming documentary and distributors are now steering clear of it. In the wake of the controversy, it’s unlikely that he’ll ever be invited to host the Oscars.

Judy Gold is fond of quoting her fellow comedian, Eddie Sarfaty: “Going to a comedy club and expecting not to get offended is like going on a roller coaster, expecting not to get scared.”

That quote appears on the first page of her 2020 book, “Yes, I Can Say That: When They Come for the Comedians, We Are All in Trouble.” But these days, umbrage at a joke – even one uttered many years ago – can have serious consequences. For Kevin Hart, it meant losing the chance to host the 2019 Academy Awards ceremony after a tweet from 2011 surfaced in which he joked about worrying that his young son was gay. For Shane Gillis, it meant getting fired from “SNL” four days after he was hired because of homophobic and racially controversial lines he had used on a podcast.

Cancel culture is predominantly a far-left phenomenon, but it also exists on the right. Samantha Bee and Kathy Griffin have had to apologize for jokes at the expense of former President Donald Trump and members of his family.

“I’m observing comedians being scared to say things they normally would say,” says Ms. Gold, who adds that some of the edgiest comedians are running jokes past her out of fear of a backlash. “It’s stifling the writing.”

The tension between cancel culture and comedy comes down to this: Should a comic be fired or ostracized for ... uttering words?

Ms. Gold observes that when you hear a song on the radio you don’t like, you can change stations. So why do those who take offense at comedy feel the need to marshal campaigns against the comic?

“It’s called a sense of humor,” she says. “It’s just like you have a sense of taste. You like salty food; you don’t like salty food. You like sarcasm; you don’t like sarcasm.”

Telling people they’re not allowed to laugh at something, she says, doesn’t mean we won’t find those things funny, because laughter is an involuntary response.

In “The Closer,” Mr. Chappelle tells the audience, “Sometimes the funniest thing to say is mean. Remember, I’m not saying it to be mean: I’m saying it because it’s funny.”

Mr. Nesteroff, the comedy historian, says some people think the role of the comedian is to convey truth. He counters that a comic has just one job: to make people laugh.

“Less than 1% of the world’s population is funny,” he says. “That’s a real superpower. Any person can speak truth to power – not everyone can be funny.”

But if some find a joke hurtful, is it worth the trade-off of getting the laugh? Many comedians abide by the ethos that one should punch up, not down.

“There’s almost a hierarchy,” says Dr. Gill, the former Navy recruit turned political podcaster. “Rule No. 1, make fun of yourself. Rule No. 2, make fun of the oppressors. And rule No. 3, never make fun of those that you would want to protect from either of those first two things.”

Dr. Gill believes that rant comedy – the sort of angry opinionated humor exemplified by the likes of Bill Hicks and Lewis Black – is dying out because fewer people find it funny anymore. Similarly, insult comics such as Gilbert Gottfried seem passé.

“If we’re swinging the pendulum to be more conscientious than we need to be, where’s the harm in that?” asks Dr. Gill.

Instead of deploying jokes as a weapon of cruelty, the rape survivor believes comedy can be used to heal. Hope springs from humor, she says. To quote the old adage, “If we don’t laugh, we cry.”

Ultimately, if a comedian’s goal is to make as many people laugh as possible, it makes sense to be inclusive. At heart, humor springs from a desire to be social. When people laugh collectively, they bond, and that experience creates community even if it’s just for a moment in a comedy club.

Ms. Gold can attest to that. In the 1990s, she came out as a gay parent. Onstage, she found that when she started quipping about her children, audiences related to her as a parent. That common ground helped to foster acceptance.

Back at the comedy club in Everett, Mr. Crohn is musing on what a great time it is to be a comedian, despite all the politically correct restrictions. The industry is experiencing a boom, and the comedy classes he teaches have a waiting list for the first time. Credit the proliferation of platforms available to purveyors of laughter: YouTube, TikTok, Twitter, and podcasts. Mr. Crohn’s comedy album “It’s Enough Already,” which often riffs on his Jewishness, is on Spotify. (Sample joke: “I saw a bumper sticker that said, ‘Jesus for president.’ I said, ‘Who’s going to elect a Jew?’”) The parameters of what comedians can say may be narrower now, but he says it challenges them to write better jokes.

“Audiences now are so great because they do appreciate really well-crafted material that’s, like, personal and about you,” says Mr. Crohn. “That’s why everybody goes to comedy. They want to hear something about themselves said by somebody else.”