Supreme Court turns to history: How does past speak to the present?

Loading...

Laughter is not a rare occurrence during oral arguments at the U.S. Supreme Court, but it is rare that Justice Samuel Alito is the jokester.

Yet late in 2010, the high court heard a case about a California law restricting the distribution of violent video games. If the government can censor violent content, asked Justice Antonin Scalia, then what next? Smoking? Drinking?

The deputy attorney general of California began to answer, then Justice Alito cut in.

Why We Wrote This

As the U.S. moves forward, its highest court is looking to the past. But putting a premium on history and tradition leaves open several questions. As one historian puts it: ŌĆ£What do we mean by history and tradition? Whose history? Whose tradition?ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I think what Justice Scalia wants to know is what James Madison thought about video games,ŌĆØ he quipped.

A decade later, Justice Alito ŌĆō decidedly not joking about history or how to interpret the original meaning of the Constitution ŌĆō wrote the opinion striking down the right to abortion. Unenumerated rights ŌĆō which are not explicitly mentioned in AmericaŌĆÖs founding document, but instead implicitly protected by the 14th Amendment ŌĆō are constitutional only if they are ŌĆ£deeply rooted in [our] history and tradition,ŌĆØ he wrote in Dobbs v. Jackson WomenŌĆÖs Health.

ŌĆ£Historical inquiries of this nature are essential whenever we are asked to recognize a new component of the ŌĆśliberty,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he added.

History has always played an important role in American law, and the Supreme Court ŌĆō populated by individuals with lifetime appointments and little public accountability ŌĆō is inherently less likely to be swayed by current thought than the rest of government.┬ĀBut deciding the legal direction of the country by looking backward can be an awkward enterprise, particularly when it concerns applying constitutional rights to modern times.

Focus on the past has in different eras, such as the 1850s and 1930s, seen the court fall so out of step with contemporary values and beliefs that it brings its institutional strength to a breaking point. After a momentous term in which the justices made historical analysis central to the reshaping of key rights, some believe the Supreme Court may now be entering a similar era.

As the U.S. moves forward, its highest court seems preoccupied with looking backward, with a particular view of history underpinning key components of opinions expanding gun rights, erasing the right to abortion, and shifting how the boundary between church and state is guarded. And this kind of historical analysis ŌĆō which critics call ŌĆ£law office historyŌĆØ ŌĆō is primed to play a critical role in the U.S. legal landscape in the coming years.

The results could be Justice ScaliaŌĆÖs dream of interpreting laws and rights based on the foundersŌĆÖ vision at the time of the countryŌĆÖs origin.┬ĀOr the ŌĆ£dead handŌĆØ of the past, as President Franklin Roosevelt put it, might steer America toward values and beliefs now considered obsolete or condemned by a majority of society.

ŌĆ£The past is really a different place,ŌĆØ says Saul Cornell, a professor of American History at Fordham University,┬ĀŌĆ£and most of us would not be very happy or very comfortable if we had to live [there].ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Historians naturally ask questions like, ŌĆśWho said it? Why did they say it?ŌĆØ┬Āadds Dr.┬ĀCornell. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs not how lawyers think.┬ĀIf you had to think about that every time you ask a legal question you would never get anything done,ŌĆØ he┬Ācontinues. ŌĆ£But thatŌĆÖs also why this movement of the court is very bad ŌĆō and at a time when the court cannot afford to lose any more public confidence.ŌĆØ

Roots in common law

U.S. law has roots in English , which holds, broadly, that law is derived from past judicial decisions. History has thus been a factor in judicial decisionmaking since AmericaŌĆÖs founding. But the rise of originalism has made historical analysis increasingly prominent.

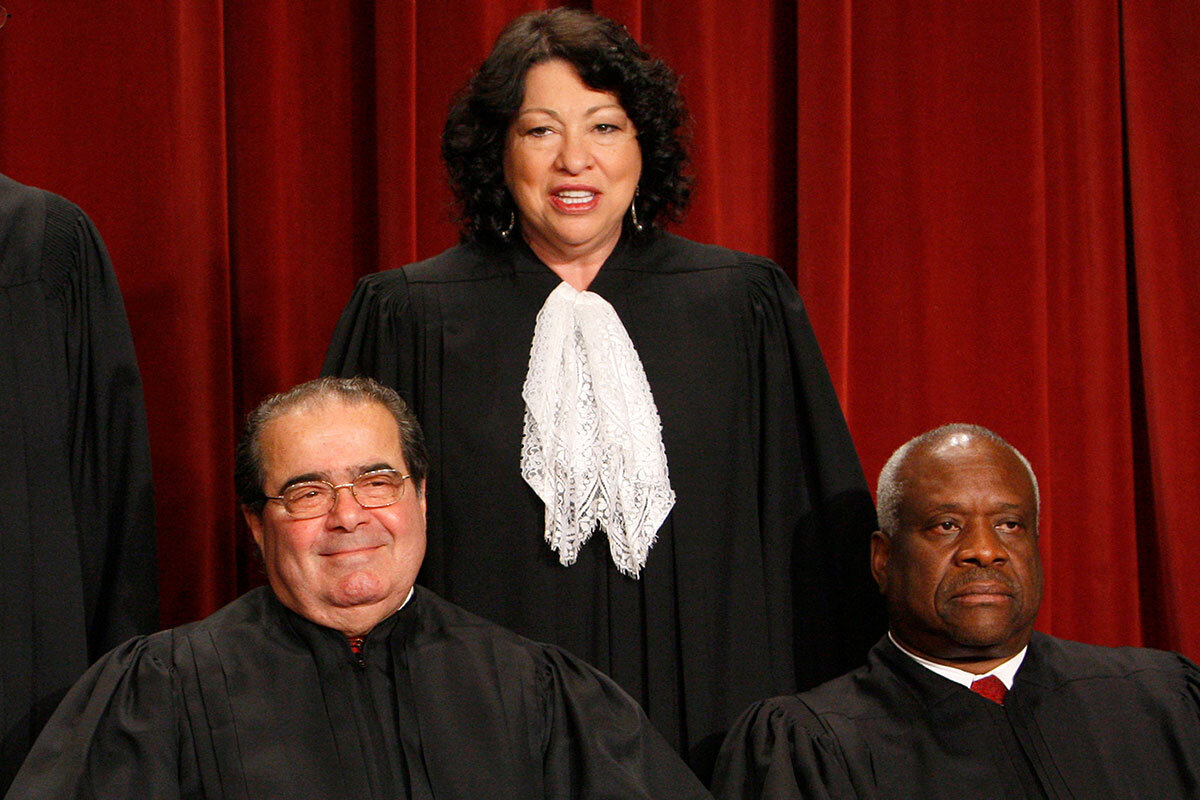

Scalia pioneered this philosophy ŌĆō that judges should interpret the Constitution in line with what it meant at the time of writing ŌĆō starting in the 1980s. It has since flourished in the federal judiciary, and now commands a majority of the high court after three appointments in four years by former President Donald Trump.

On June 23, Justice Clarence Thomas, the courtŌĆÖs most senior originalist, wrote a decision that both expanded gun rights and the role of history in refereeing gun control policies.

His majority , in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, holds that the Second Amendment confers a right for law-abiding citizens to carry guns in public. Further, he said that when courts evaluate gun policies, they must consider only if the policy ŌĆ£regulation is consistent with this NationŌĆÖs historical tradition of firearm regulation.ŌĆØ

In so doing, he cut in half a ŌĆ£two-stepŌĆØ process used throughout the federal courts that combined historical analysis with scrutiny of government claims that its public safety concerns justify the burden on the rights of gun owners. Historical analysis ŌĆ£can be difficult,ŌĆØ wrote Justice Thomas. But ŌĆ£in our view [itŌĆÖs] more legitimate, and more administrable, than asking judges to ŌĆśmake difficult empirical judgmentsŌĆÖ about ŌĆśthe costs and benefits of firearms restrictions.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

The next day came Dobbs. The central act of Justice AlitoŌĆÖs┬Ā in Dobbs v. Jackson WomenŌĆÖs Health was to eliminate a womanŌĆÖs right to abortion by overturning Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, two precedents holding that the 14th AmendmentŌĆÖs right to due process guaranteed a right to abortion. The due process provision has been read to protect other rights not written in the Constitution ŌĆō including the rights to contraception, same-sex intimacy, and same-sex marriage.

The following Monday, in , a case concerning prayer in public schools ŌĆō the high court announced a new test courts should apply when evaluating claims that behavior violates the ConstitutionŌĆÖs prohibition on the ŌĆ£establishmentŌĆØ of religion. ŌĆ£This Court has instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ŌĆśreference to historical practices and understandings,ŌĆÖŌĆØ wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch.

All three of those cases were decided 6-3, along the Supreme CourtŌĆÖs ideological divide.┬Ā

The ŌĆ£Glucksberg testŌĆØ vs. evolving liberty

The notion that an unenumerated right must be ŌĆ£deeply rootedŌĆØ in history comes from a 1997 case, Washington v. Glucksberg, where the court ruled unanimously that the due process clause doesnŌĆÖt protect a right to assisted suicide.

Since then, the ŌĆ£Glucksberg testŌĆØ appeared only in dissents. Scalia cited the ruling in 2003 in his to Lawrence v. Texas, which established a right to consensual same-sex intimacy. And in 2015, when the court extended the right of marriage to same-sex couples in Obergefell v. Hodges, both Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Alito cited the ruling in their dissents.┬Ā

Justice Anthony Kennedy, the author of Obergefell, countered that if rights were ŌĆ£defined by who exercised them in the past, then received practices could serve as their own continued justification and new groups could not invoke rights once denied.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Rights come not from ancient sources alone,ŌĆØ he added. ŌĆ£They rise, too, from a better informed understanding of how constitutional imperatives define a liberty that remains urgent in our own era.ŌĆØ

The decisive vote for many of his 30 years on the court, Justice Kennedy ensured that the court viewed the ŌĆ£libertyŌĆØ protected by the due process clause as ŌĆ£evolving, and not historically static or frozen,ŌĆØ says Reva Siegel, a professor at Yale Law School.

Justice Kennedy retired in 2018, and the more conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh replaced him. What you see in Dobbs, adds Professor Siegel, is ŌĆ£a court, shaped by President Trump, repudiating this historically evolving understanding of the liberty guarantee.ŌĆØ

In asserting that the right to abortion is not ŌĆ£deeply-rooted,ŌĆØ Justice Alito devotes dozens of pages to the history of abortion jurisprudence, starting in 13th century England. The bulk of the historical analysis focuses on the mid-19th century, when states started to criminalize abortion. (Twenty-eight states did so when the 14th Amendment was ratified, and 30 states did so, except to save the life of the mother, when Roe was decided.)┬Ā

Critics both contest, and contextualize, his┬Āframing of history. The opinion discounts 18th and early 19th-century American laws permitting abortion before quickening (roughly 18 weeks of pregnancy), and ignores demands of 19th century abolitionists and suffragists for bodily autonomy. The focus on the 19th century is ŌĆ£convenient,ŌĆØ wrote Professor Siegel in a Washington Post , because that was also a period when the law did not guarantee a womanŌĆÖs right to property, earnings, or the vote.┬Ā

ŌĆ£History is an after-the-fact rationale for decisions reached on other grounds, in most cases ŌĆō certainly in most big cases,ŌĆØ says Eric Segall, a professor at Georgia State University College of Law.┬ĀŌĆ£Our Constitution is full of lots of vague, important aspirations. We should flesh out these vague aspirations of equality, fairness, due process, free speech, by todayŌĆÖs values, not the values of racists and sexists.ŌĆØ

Looking further back, Justice Alito turns to the 17th century jurist Lord Matthew Hale, who he cites seven times in Dobbs. Hale may well be a prolific figure in early common law history, but multiple scholars have noted the depths of his misogyny. ┬ĀHe did not believe in marital rape, considered womenŌĆÖs bodily autonomy a┬Ā, and┬Āsentenced women to hang as witches.

But these historic details may not be important to the legal argument, some scholars say.

ŌĆ£There are debates about some parts of the history, but [Justice AlitoŌĆÖs] basic argument is, as of the date Roe was decided, there was no right to abortion that had deep roots in our history,ŌĆØ says Lawrence Solum, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. ŌĆ£Of course heŌĆÖs right about that, because at the time Roe was decided abortion was unlawful.ŌĆØ

That raises the question that Justice Kennedy debated with his colleagues.

ŌĆ£What do we mean by history and tradition? Whose history? Whose tradition?ŌĆØ asks Jack Rakove, a professor of history and political science at Stanford University.

ŌĆ£If you think about the systemic biases embedded [at those times], why would you stick to that,ŌĆØ he adds, ŌĆ£rather than ask where has the country come?ŌĆØ

What happens when history disagrees?

Additional problems can arise when the historical record presents conflicting arguments.

Justice ThomasŌĆÖ historical analysis in Bruen ranges from the 1300s to 2008. Both parties made arguments, but New YorkŌĆÖs arguments highlighting many historical examples of restrictions on gun possession in public ŌĆ£does not demonstrate a tradition of broadly prohibiting the public carry of commonly used firearms for self-defense,ŌĆØ he concluded.

The 1328 Statute of Northampton, for example ŌĆō cited as an early example of restrictions on public carry ŌĆō ŌĆ£has little bearing on the Second Amendment,ŌĆØ he wrote. And while public-carry restrictions ŌĆ£proliferate[d]ŌĆØ after the Amendment was adopted, none compare to New YorkŌĆÖs law, he wrote, and those that did ŌĆ£are outliers.ŌĆØ

Moving forward, states and localities must identify ŌĆ£a well-established and representative historical analogue, not a historical twinŌĆØ for their policies to be constitutional, he clarified. That kind of analogical reasoning is ŌĆ£a commonplace task for any lawyer or judge,ŌĆØ he added.

But there was little other guidance for governments and lower courts on what critical mass of historical policies are enough to pass constitutional muster, according to the dissenting justices.

ŌĆ£The Court does not say how many cases or laws would suffice ŌĆśto show a tradition of public-carry regulation,ŌĆÖŌĆØ wrote Justice Stephen Breyer, who retired at the end of this term.

ŌĆ£At best,ŌĆØ he added, ŌĆ£the numerous justifications that the Court finds for rejecting historical evidence give judges ample tools to pick their friends out of historyŌĆÖs crowd.ŌĆØ

Logistical challenges will be difficult for lower courts, he noted, because they have higher caseloads and fewer research resources. Also, judges are well-trained in how to weigh a lawŌĆÖs objectives against how it achieves those objectives, he wrote, but judges ŌĆ£are far less accustomed to resolving difficult historical questions.ŌĆØ

Justice Thomas acknowledges that judges themselves canŌĆÖt be expected to perform extensive historical research. Instead, he wrote in a footnote, parties in the cases should. Because the legal system is adversarial by nature, courts are ŌĆ£entitled to decide a case based on the historical record compiled by the parties.ŌĆØ

The parties who file briefs in cases ŌĆ£donŌĆÖt have an incentive to provide a history that undermines their preferred position,ŌĆØ says Jack Balkin, a professor at Yale Law School. ŌĆ£So essentially what youŌĆÖre going to get is different accounts of history, and the judges are going to pick the ones they like best.ŌĆØ

This is a departure from the typical originalist approach, scholars say. In the District of Columbia v. Heller, for example ŌĆō the Supreme CourtŌĆÖs 2008 ruling establishing an individual right to keep a handgun in the home ŌĆō the historical analysis focused on what the Second Amendment meant at the time it was written.

In Bruen, ŌĆ£the Founding turns into a long Founding, if you will,ŌĆØ┬Āsays Jonathan Gienapp, a history professor at Stanford University.

ŌĆ£Instead of the [ConstitutionŌĆÖs] authors, weŌĆÖre going to look at the people who put it in motion,ŌĆØ he adds. ŌĆ£It places an extraordinary emphasis on a new kind of constitutional and legal history.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The past speaks to the presentŌĆØ

The Supreme Court imposing old values on a country that broadly chafes against that vision has happened in the past.

In the 1850s, as the North grew in economic and political strength with the Republican Party, a court comprised mostly of southern Democrat appointees routinely ruled in favor of preserving slavery, culminating in the Dred Scott decision in 1857. Later, in the 1930s, a conservative court that had been regularly striking down progressive reforms like establishing a minimum wage, banning child labor, and breaking up monopolies clashed with Roosevelt over his New Deal policies.

Robert Jackson, RooseveltŌĆÖs attorney general and a former justice, described the judiciary as ŌĆ£the check of a preceding generation on the current one and nearly always the check of a rejected regime on the one in being.ŌĆØ

While the past term was certainly a dramatic one, it doesnŌĆÖt necessarily mean the court will continue to make history more important in more areas of law.

ŌĆ£Because these [big] cases all were decided in June 2022 you might think, ŌĆśHey, thereŌĆÖs this big new thing, the Supreme Court is moving to a tradition and history approach,ŌĆÖŌĆØ says Professor Solum. ŌĆ£But the truth is that all of these cases have their roots in Supreme Court cases that go [way] back.ŌĆØ

Furthermore, if the court wanted to extend this method of historical analysis to other provisions of the Constitution, the court would have to choose to do so.

ŌĆ£The reasoning of the court in Dobbs is limited to substantive due process, and the reasoning of the court in Bruen is limited to the Second Amendment,ŌĆØ says Professor Solum.

Other legal scholars arenŌĆÖt so sure, however, particularly when it comes to what the Dobbs ruling could mean for more recent substantive due process rights.

ŌĆ£This court is interested in extending history and tradition into other areas of law,ŌĆØ says Professor Siegel.

Justice AlitoŌĆÖs opinion emphasized that because the right to abortion destroys ŌĆ£fetal life,ŌĆØ it is ŌĆ£fundamentally differentŌĆØ from other substantive due process rights. The ruling could have stopped there, notes Professor Siegel, but the fact it invoked history and tradition as well means that it ŌĆ£calls their legitimacy into question.ŌĆØ

The extent to which history and tradition will be a focus for the Supreme Court moving forward remains to be seen, but what the past term shows is how different the practice of law and the practice of history can be.

ŌĆ£America is very much built around an understanding of its past. So fighting over that, claiming that for authority is always going to be important,ŌĆØ says Dr. Gienapp. But history and the law operate very differently, he adds.

Historians focus on ŌĆ£what has changed,ŌĆØ he says. Lawyers and judges,┬Āmeanwhile, are ŌĆ£often trying to draw more or less straight lines between the past and present. ŌĆ” TheyŌĆÖre often confident, you might say overconfident, in how the past speaks to the present.ŌĆØ