Hunting for evidence, Secret Service unlocks phone data with force or finesse

Loading...

On July 20, 2014, a missing Conway, N.H., teenager walked back into her home, ending a heinous nine-month-long kidnapping��ordeal.

About a week later, police arrested��Nathaniel Kibby at his home and charged him with the abduction. During��a warranted search, investigators confiscated several��mobile devices��that may have contained valuable information in the case.

But there was one smartphone they couldn't crack, a password-protected��ZTE.��That's when��New Hampshire State Police��turned to the Secret Service, which has become��a��go-to��federal agency��to help��police departments with warrants��to��extract data from��password-protected smartphones and other devices for criminal investigations.

The information on the ZTE contained "a huge piece of evidence," says Sgt. Michael Cote, a New Hampshire State Police detective.��In May,��Mr. Kibby��pleaded��guilty to kidnapping and rape, among other charges. A judge sentenced him��to consecutive��prison terms��totaling 45 to 90 years.

As smartphones are interwoven into daily life – collecting text messages, emails, phone numbers, photos, location data, and chat logs – they can be incredibly important to criminal investigators. And since many of the phones that police confiscate are locked by passwords or contain encrypted data, law enforcement��agencies are��looking for new and creative ways of��getting��that��evidence out.

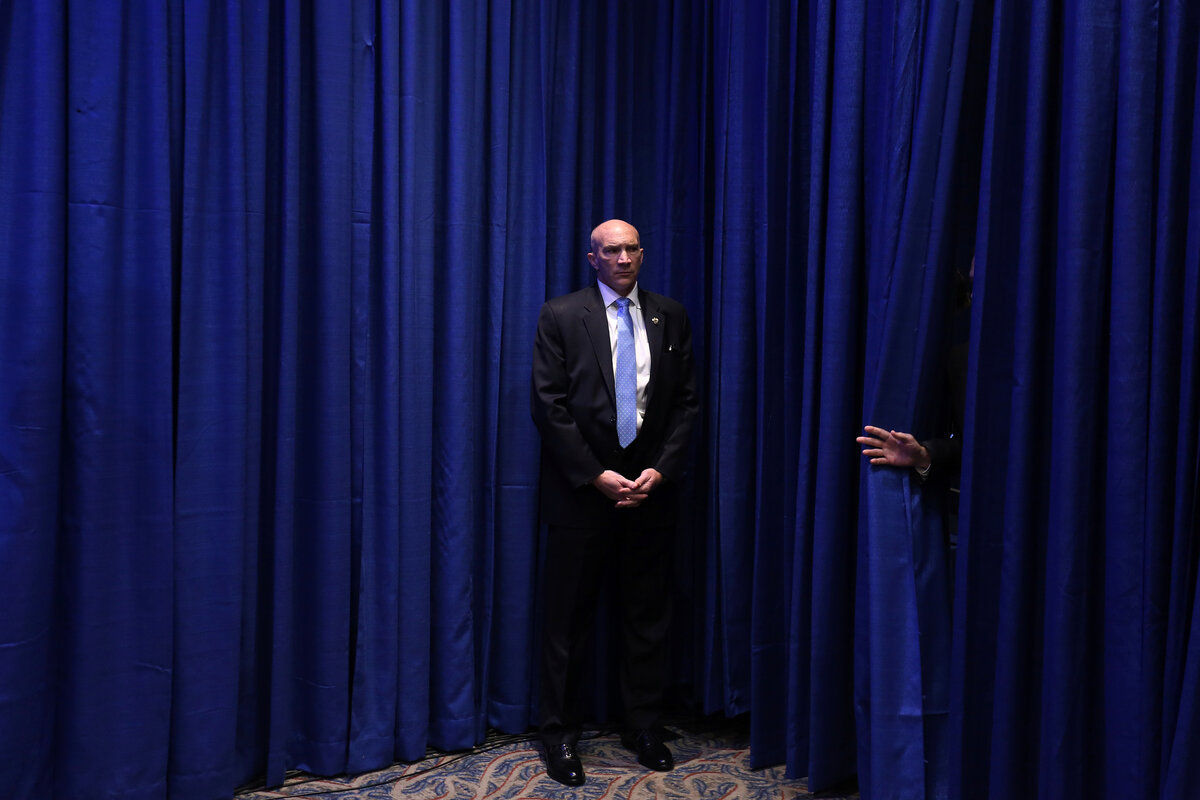

While some large metropolitan police departments may have resources to hack phones themselves,��the��Secret Service, part of the Homeland Security Department, has become a valuable resource for��law enforcement units��that may not have��strong enough decryption tools.

To do that work, the Secret Service has been running its Cell Phone Forensics Facility, a��10,000 sq. foot lab, in Tulsa,��Okla., since 2008. Two��Secret Service agents work��there full time, aided by��students and faculty at the University of Tulsa Cyber Corps Program. The facility trains federal agents in digital device forensics, invents its own hardware and software for parsing evidence from electronics, and uses that��technology to examine��40 phones a year from police departments around the country.

When the lab received the ZTE phone in the Kibby case, it attempted to open it by connecting forensic software that is designed��to exploit specific vulnerabilities in��a��particular device.��But��it was��still unable to get around the��phone’s password.

After roughly a week, the Tulsa facility was able to��take the device apart and pull the flash memory chip out to read the memory,��said James Darnell, assistant to the special agent in charge at the lab. In this case, the��Secret Service agents applied physical force to gain access to Kibby's ZTE.

The experts at the lab often have to get creative to crack phones. In another case, involving a��password-locked Huawei��H883G��phone, agents bought��multiple copies of the same model and practiced carefully polishing off material from the back of the device with an automated sander.��

Often, agents can apply heat to phones to open them up. But��Huawei built this particular model in a way that applying too much heat could damage its memory. So, agents��sanded off material from the back of the Huawei H883G device to excise sexually explicit images for a case involving a different New Hampshire man.

A less damaging approach to getting into password-protected phones can often��involve��connecting the device to special software designed to exfiltrate data.��

In one case, agents used a tool known as the Cellebrite UFED Touch Physical Boot Loader��to obtain information from a Samsung Galaxy S5. The device��is part of an ongoing��first-degree murder case in Virginia. The product��developed by��Cellebrite, an Israeli firm that makes phone-cracking software, is��designed��to��copy the phone’s��entire memory,��Mr. Darnell��said.

Typically, a device��takes anywhere from a day to a month to break into, depending on whether Secret Service computer engineers need to disassemble the device and software to figure out how it was programmed.

Digital tools "simply do not go around the passwords on many phones," Darnell said.

,��FBI Director James Comey described the problem of law enforcement's inability to access evidence on some phones that are encrypted as "going dark," meaning agents are unable��to extract��data even with a warrant.

Perhaps the most high-profile example of this issue involved the iPhone used by��one��shooter in the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack. The FBI��obtained a court order to compel Apple's help to open��the encrypted phone. The company refused, saying its assistance could��effectively��weaken��security for all of its customers. The FBI eventually opened the device with the help of an unidentified third party.

"Technical assistance in and of itself isn't of concern from a privacy perspective," says Gabe Rottman, deputy director of the Freedom, Security and Technology Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology.

"But to the extent that the Secret Service or the FBI or any other federal agency becomes kind of a gun-for-hire when you're talking about hacking into people's cellphones or computers or other electronic devices, it could become an issue, just as it starts to normalize that practice,"��Mr. Rottman adds.

But many��cybersecurity experts say the��Secret Service's work on phone hacking is exactly what law enforcement needs to be doing to confront the "going dark" problem.

Watering down encryption on phones is "not a good path," says��Dave Aitel, a former National Security Agency��research scientist who currently runs the cybersecurity firm��Immunity.��"The path of hacking is much nicer – from a policy perspective."

The Secret Service is adamant that it examines phones only when a judge has issued a warrant��to��authorities.��It also does not refer to its work as "hacking" phones.

Fortunately for investigators, the data on both the ZTE and��Huawei��phones that Secret Service agents worked on wasn't encrypted.��"If a device is using encryption at rest ... that could be problematic, especially if the implementation of the encryption is good,” he said.��Encryption at rest protects data while it's stored inside the device.

The agency wouldn't say how many phones from which it can't access data.

When it��comes to breaking into phones, it's tougher to access��devices��that��aren't as popular as iPhones or Samsungs, according to investigators. Most forensics technology developers don't waste their time trying to find design flaws in off-brand phones, they said.

"A cheaper phone that might be less popular, it seems like it'd be easier for the vendors to get into it," says Darnell of the Secret Service phone lab. "But it's actually quite the opposite."