Young Senegalese challenge their country to think ‚Äď and buy ‚Äď local

Loading...

| Dakar, Senegal

Growing up in Senegal, Mohammed Wade learned all about French politicians, like Gen. Charles de Gaulle, in school.

So this spring, when he found out that the Dakar thoroughfare where he runs his family‚Äôs jewelry shop was being renamed Boulevard Mamadou Dia, he admits that his first reaction was, ‚ÄúWho?‚Ä̬†¬†

‚ÄúWe learn very little about our own history,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Wade, pulling a silver bracelet from a glass case. Mr. Dia, the first prime minister after Senegal won its independence, wasn‚Äôt in the curriculum. ‚ÄúInstead, we learn about French history, French politicians. And it‚Äôs always portraying them in a positive light.‚ÄĚ

Why We Wrote This

France and its former African colonies have a relationship so tight it has its own portmanteau: Françafrique. But many in Senegal, from baguette makers to fashion designers to politicians, say it's time for the country to be less reliant on its former ruler.

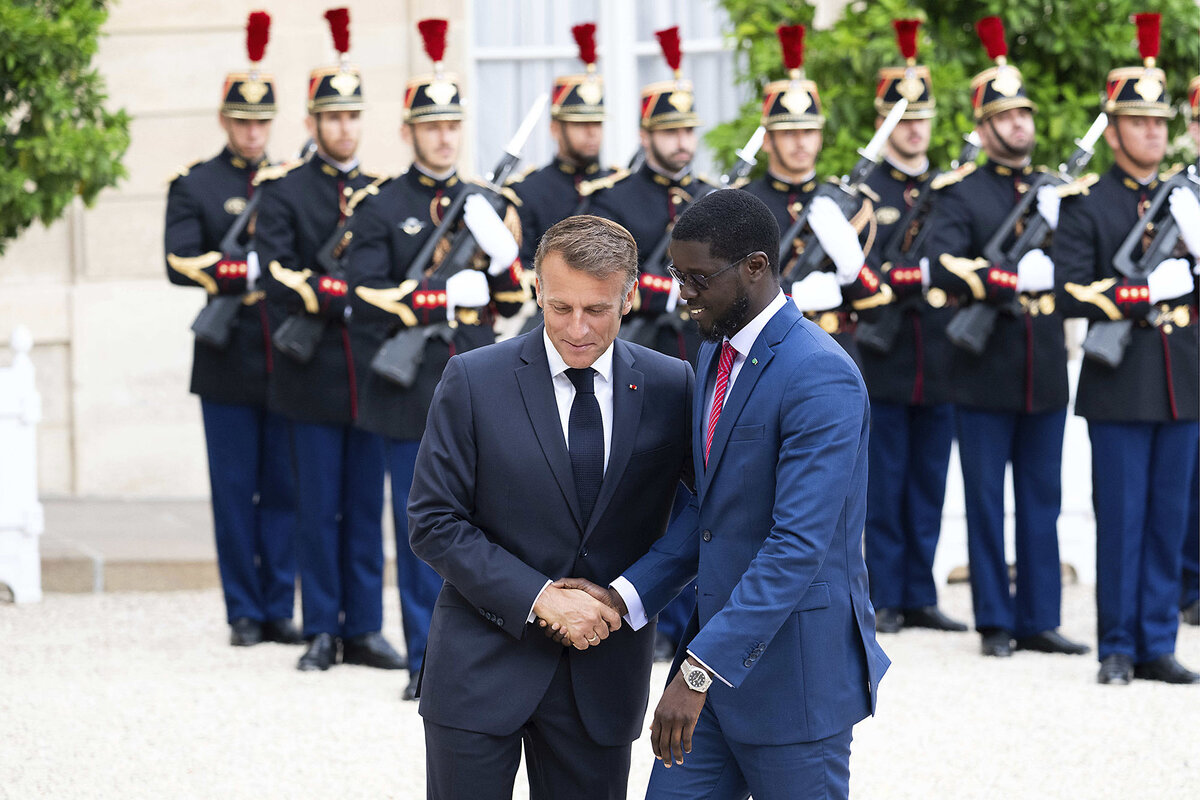

Since his surprise election in March 2024, Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has set out to forge a new relationship between Senegal and its former colonizer, France. His administration plans not only to change street names, but also the history taught in school textbooks. It has kicked out the French military and wants to bolster Senegal‚Äôs industries to become more self-sufficient.Őż¬†

The country‚Äôs artisans and activists are getting on board, too. They say it‚Äôs not a matter of being anti-French but, instead, pro-Senegal.Őż

‚ÄúThe new administration is opening a Pandora‚Äôs box and taking risks,‚ÄĚ says Abdoulaye Ndiaye, a Senegalese economist and assistant professor at the New York University Stern School of Business. ‚ÄúThat takes courage.‚Ä̬†

A modern twist on the classics

After 16 years as a businessman in the United States, Moustapha Sall was used to taking risks. Still, when he moved back to Senegal five years ago, his new idea for his family‚Äôs bakery, Boulangerie Jaune, seemed to many around him impossibly bold: to make bread with Senegalese wheat.Őż

The Senegalese eat around 10 million baguettes a day ‚Äď one for every two people in the country. But nearly all of them are made with flour ground from foreign wheat. In fact, the country imported ¬†of wheat last year, mostly from France and Russia, according to the National Agency for Statistics and Demography.Őż

‚ÄúAt first when I told people we could grow wheat in Senegal, no one believed it,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Sall, standing in a robin‚Äôs-egg-blue kaftan next to a shelf of millet grain baguettes in Boulangerie Jaune. ‚ÄúThey said, ‚ÄėIt‚Äôs impossible.‚Äô‚ÄĚ

Today, Mr. Sall, with financial support from the government, has transformed his family bakery into a pioneer in the industry, creating baguettes and bread loaves that are made with Senegalese grains. He is part of a broader national effort to reduce Senegal‚Äôs reliance on foreign grains, at a time when the Russia-Ukraine conflict has dramatically affected the .Őż

Producing wheat in Senegal‚Äôs tropical climate remains an uphill battle. But Mr. Sall hopes that Senegal will soon be self-sufficient in wheat production, something he says can be achieved with the right equipment and ‚Äúif we believe in ourselves.‚Ä̬†

Part of that self-belief means showing more national pride, say the country’s fashion designers, who are pushing for the recognition of fabrics and clothing made in Senegal. Around 60% of fabrics used here are imported from Asia, and secondhand clothing from Europe and the U.S. dominates the wholesale market.

‚ÄúSenegalese who have the means are starting to understand the value of buying something made here,‚ÄĚ says El Hadj N‚ÄôDiaye, the production floor manager at Aissa Dione Tissus, a Dakar-based textile company that uses traditional weaving methods to create handwoven tapestries and fabrics. ‚ÄúWe‚Äôre handing down these techniques to the new generation, to teach them the importance of traditional work.‚ÄĚ

Even the president, Mr. Faye, has gotten on board, swapping the stiff Western suits favored by his predecessor, Macky Sall, for African kaftans during official meetings.Őż

‚ÄúFor so long, we‚Äôve been encouraged to wear European, Western clothing in professional spaces,‚ÄĚ says Fatima Zahra Ba, owner of So‚ÄôFatoo, a luxury clothing brand in Dakar. Her firm promotes the ‚Äútradi-modern‚ÄĚ style worn by Mr. Faye, blending classic cuts with a contemporary flourish. ‚ÄúBut we‚Äôre African. We should be able to wear African clothes without it being seen by the West as ‚Äėexotic,‚Äô‚ÄĚ she says.

A new relationship

For Senegal, calls for self-determination and national pride are inextricably linked to France. This July, at the behest of Mr. Faye, France pulled its last remaining troops out of Senegal, where French forces had been stationed since the country gained independence in 1960. The new president has also said he is pondering whether Senegal should abandon the CFA franc, a regional currency originally created by the French colonial government.

But many here say building a more independent Senegal is more complex than just turning away from France.

‚ÄúSovereignty is not about being isolated or anti-French,‚ÄĚ says Souleymane Gueye, the chairman of the Front for an Anti-Imperialist, Popular, and Pan-African Revolution, or FRAPP, an activist collective that promotes revolution and national sovereignty. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs about African solidarity, and mastering risks ‚Äď economic or otherwise.‚ÄĚ

Indeed, Senegal remains deeply economically entwined with France, in a relationship visible everywhere from its Auchan supermarkets and La Vache Qui Rit cheese wedges stacked on its shelves, to its Total gas stations and the Peugeots, Citro√ęns, and Renaults queuing to fill up there. The dominance of French brands has sparked protests over the years, as well as calls of ‚ÄúFrance, d√©gage‚ÄĚ ‚Äď "France, get lost."¬†

Still, some citizen activists say the goal should be to change Senegal’s unequal relationship with France rather than to cut ties completely.

‚ÄúWe live in a world of globalization, where countries need one another,‚ÄĚ says Fou Malade, a Dakar-based rapper and one of the founders of citizen activist group Y‚Äôen a Marre ‚Äď ‚ÄúFed Up.‚ÄĚ ‚ÄúTelling France to ‚Äėget lost‚Äô isn‚Äôt going to solve anything.‚ÄĚ

Back on the newly dubbed Boulevard Mamadou Dia, business partners Cheikh and Mohammed, who asked to use their first names only, sit at their humble stall selling chestnuts. Mohammed says most people here have no idea the boulevard has changed its name ‚Äď but they will soon.

‚ÄúWhen you‚Äôre young, you learn what teachers tell you about France and colonization,‚ÄĚ he says, chewing on a licorice root stick. ‚ÄúBut hopefully now young people will learn who Mamadou Dia is, and all that he did for this country.‚ÄĚ