Facing down jail and wealthy foes, Arab rights defenders soldier on

Loading...

| CAIRO, Egypt, and AMMAN, Jordan

On a December Thursday in a nondescript Cairo apartment building, a table is spread with plastic containers of Egyptian morning mainstays – fava beans, taamiya, scrambled eggs, and falafel. And a box of Dunkin' donuts.

Reporters at the online newspaper Mada Masr are gathering for a tradition observed in newsrooms across the world: the end-of-week staff breakfast.

As they break bread, laughter and gossip fill the air. There are no obvious signs of the police raid a few weeks earlier that led to the brief detention of the paper’s top editors – except, that is, the bolted front door.

Why We Wrote This

If support for democratic norms and institutions is eroding in the West, where does that leave rights activists and journalists in the Arab world? Seventh in our global series “Navigating Uncertainty.”

At Egypt’s last independent media outlet, which reports in a country that jails more journalists than almost any other, displaying normalcy is not just a coping mechanism, it’s a moral code.

“We live and work like any other news organization. We won’t let repression change us,” says Sharif Abdel Kouddous, an editor.

That sort of stubborn determination is common to reporters and human rights defenders throughout the Middle East who are fighting – and sometimes defeating – a wave of repression.

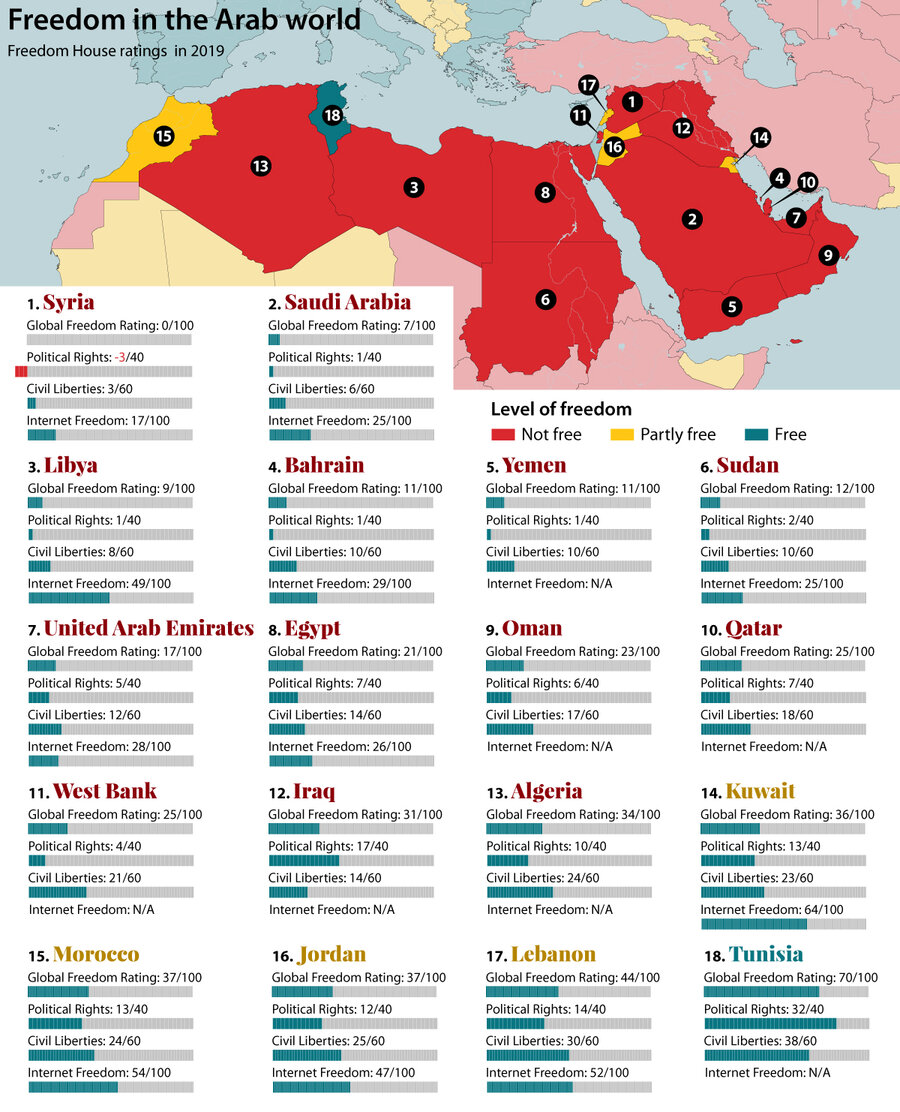

As Europe, Latin America, and even the United States witness a steady erosion of democratic norms and institutions, Arab activists and journalists are embroiled in an all-out war in defense of those values, facing arrest, sham trials, even torture.

If today the world order is shaking, the Arab world, in tectonic terms, has been feeling the foreshocks for nearly a decade.

In much of the region, which less than 10 years ago experienced an awakening of political and personal freedoms, culture, and the media, activism has become a matter of life or death. For in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring protests to end autocratic rule and foster democracy has come an anti-democratic counterrevolution that rages to this day.

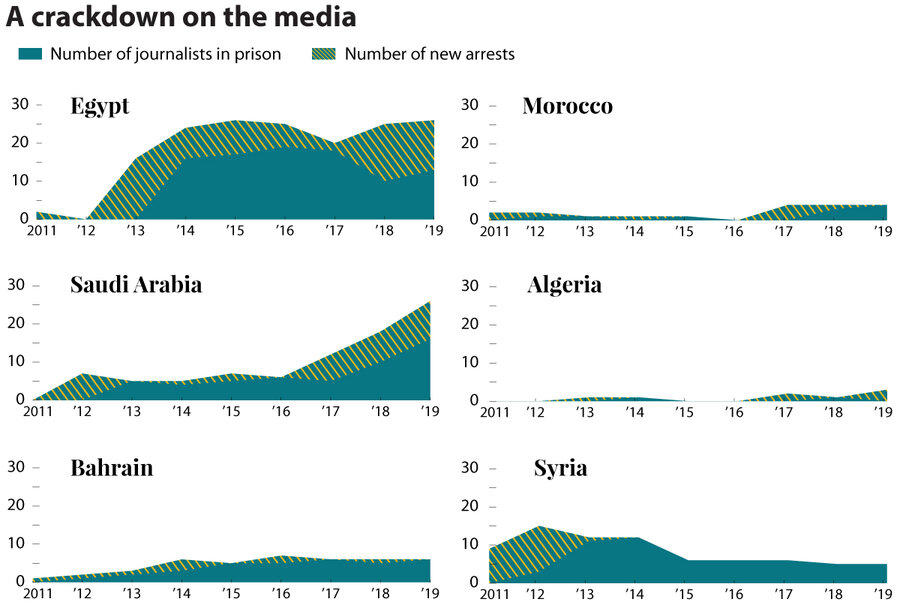

In the belief that democracy in one Arab state is a threat to all, regimes flush with petrodollars have cracked down mercilessly on political activity and media. One of the fiercest campaigns continues under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Egypt, funded by Gulf allies, who has jailed 60,000 political prisoners and dozens of journalists, according to Human Rights Watch.

Goliath with a rocket launcher

Western governments rarely talk about human rights in the Arab world these days. Consumed by political divisions at home, and lately by the coronavirus pandemic, they are more likely to praise autocratic regimes than challenge them.

The silence has an impact.

In late November, Egyptian police raided a Cairo coffee shop and arrested three independent journalists: Solafa Magdy, Hossam al-Sayyad, and Mohamed Saleh. Their detentions received no domestic or international media coverage. Today they remain in prison in cramped conditions and denied medical care, like hundreds of rights defenders and journalists across the region.

Meanwhile, America and Europe continue to enable Arab regimes’ crackdowns with money, weapons, and technology. Canadian and French firms have sold software to the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt that those governments have used to block the websites of human rights organizations and media outlets, internet watchdogs say. Former U.S. National Security Agency employees have been widely reported as saying they worked with the UAE to monitor and spy on journalists and rights defenders.

The technology has aided regimes’ use of anti-terror laws that criminalize as “terrorism” Facebook posts that are merely critical of the government.

In the words of one veteran Arab activist, “it is as if in the battle between David and Goliath, Goliath was given a rocket-launcher.”

“These regimes have the support of the West, they have money, they have armies, and they have the latest technology. What do we have?” asks Khalid Ibrahim, co-founder and director of the Beirut-based Gulf Center for Human Rights. “We only have the word. And it is our duty to get the message out any way we can.”

Activists as “terrorists”

One person fighting to get the word out is Gamal Eid, among the last human rights defenders operating in Egypt.

His Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI), which once worked to reform police practices, is now consumed with defending the growing number of Egyptians jailed for “terrorism.”

From 2013-17, ANHRI dealt with around 300 cases a year, but in 2018 and 2019 its caseload surpassed 500 a year.

Today few organizations or lawyers are willing to defend the increasingly varied range of Egyptians brought before the courts as “terrorists.” Many who dare to defend activists, such as human rights lawyer Mohamed el-Baqer, end up being arrested themselves.

Mr. Eid and his staff fear that if they shutter their doors, Egyptians being held in pretrial detention will go undefended, undocumented, and unseen.

“If it wasn’t for us, these people would be lost to the system forever,” says an ANHRI lawyer who requested anonymity. “We are their last, and only, hope.”

ANHRI defends suspected members of the former Muslim Brotherhood, which backed the government that General Sisi overthrew in a 2013 coup. It also defends a growing number of young liberal Egyptians who once supported Mr. Sisi but are now persecuted for failing to toe the regime’s line.

“We cannot turn our backs on each other because of ideological differences,” says Mr. Eid. “That is how the regime wins,” he sighs.

ANHRI has paid a heavy price. Its lawyers have been arrested, and Mr. Eid says he has been attacked by suspected regime agents twice in recent months, leaving him with cracked ribs.

He now carries pepper spray, constantly glancing over his shoulder in public. But, he says, looking out from his balcony onto the bustling Cairo street below, “The people are with me, they thank me every day for our work. That is my motivation and my protection.”

Gulf citizens step up

Activism endures, too, even in the oil-rich Gulf, where citizens must maneuver under the iron grip of monarchs who repress political life and speech with more impunity and brutality than governments anywhere else in the region.

On paper, the Gulf Arab governments seem unstoppable, thanks to their enormous wealth and decades of shared military and economic interests with Western countries that do not dare risk the sheikhs’ stability with any criticism, let alone action.

With rights organizations shuttered and traditional activists in jail, democracy and social justice have one last champion: individual Gulf citizens.

Concerned citizens are now on the front lines for human right in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and elsewhere, using social media to stand up for their communities and challenge official narratives.

They are being assisted by activists and exiles abroad providing organization, advocacy, and communications and cybersecurity knowhow.

“Mobilization on social media has been key to raise awareness and lobby on certain issues,” says Mr. Ibrahim of the Gulf Center for Human Rights in Beirut.

The end result: even with rights defenders in jail and the press muzzled, the truth is getting out, sustaining international scrutiny of the image-conscious monarchies.

In Saudi Arabia, the death in prison last month of leading rights defender Abdullah al-Hamid, reportedly for lack of medical care, triggered international condemnation.

Last year, public pressure forced the reversal of a death sentence imposed on peaceful activist Israa al-Ghomgham. And Western media repeatedly reference jailed Saudi women activists like Loujain Halhoul, tarnishing the image of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Such is the work of Sayed Alwadaei.

After taking part in pro-democracy protests in Bahrain during the Arab Spring, Mr. Alwadaei was assaulted by government agents, tortured, and imprisoned for six months; he still bears scars on his forehead. In 2012, he fled to the U.K.

From London, Mr. Alwadaei founded the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), a network of citizens and activists in his home country and abroad working to pressure Bahrain’s rulers to release activists, improve prisoner conditions, and challenge Western governments’ unwavering support for Manama.

BIRD carries the voice of prisoners and survivors to the international media and to the United Nations, sharing recordings of prisoner phone calls and firsthand testimonies of torture, abuse, and prison conditions. It has swayed public opinion at home and in the U.K., a key Bahrain supporter.

Mr. Alwadaei has changed the conversation, linking the monarchy to rights abuses, and inspiring people to question Western backing for the king. During a 2018 U.K. parliamentary debate calling attention to “continuing human rights abuses in Bahrain,” MPs criticized London’s “failed” policies and singled out Mr. Alwadaei for his “bravery and tenacity.”

“The moment they see their names mentioned in a report on torture or their image portrayed as torturers, they will think twice before they commit an abuse again,” Mr. Alwadaei says from London.

Covid-19 raises the stakes

The coronavirus pandemic has only highlighted the urgent need for independent voices in the Arab world.

As Arab regimes struggle to confront the virus and invoke emergency powers to suppress information contradicting their claims of “victory,” journalists and activists are seeking to provide dependable information.

In Cairo, Mada Masr is a lone dissenting voice challenging the pro-regime media chorus that at first downplayed the virus and now only praises the government’s response.

Its journalists have reported on the limited availability of tests, explored life under quarantine lockdown in rural villages, described how doctors and nurses are braving the front lines without protective gear, and chronicled an outbreak at the National Cancer Institute.

Meanwhile, Gulf activists have reported on the dangers Asian laborers face in crowded housing, and are mounting campaigns pressuring Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain to release political prisoners amid concerns the virus will spread in crammed jails.

Bearing witness

Despite lamenting Western indifference to their fate, Arab democrats and rights defenders say their struggle remains winnable. In fact, they like their odds. For if they can keep the flame of democracy and freedoms alive in the darkest of times, they say, the future bodes well.

“You must never feel broken or powerless, because that is the entire aim of repression and intimidation; to make you overlook your own power to hold people to account,” says Mr. Alwadaei. “Sometimes vulnerability means opportunity, and you can turn it to your favor.”

At Mada Masr, the young journalists say they have a simple strategy to survive a regime that bullies the press, blurs the lines between fact and fiction, denounces the media as “enemies,” and polarizes the nation using a with-us-or-against-us narrative: Stay above the fray.

The publication embodies classic journalistic principles: to analyze events and publish “a record of life in Egypt at a time of great social and political change” without taking sides, says managing editor Mohammed Hamama.

“We are not activists; we are witnesses,” he insists. “What we deem deserves to be witnessed, documented, and commented on for the Egyptian people and future generations – we report it.”

At the Mada Masr office, you would be hard-pressed to hear insults or complaints directed toward President Sisi or his government. The newspaper’s reports carefully weigh what the government does and says, always willing to give credit where it’s due.

The same edition might carry praise for the regime’s “ingenious” universal health care plan and a report on a corruption scandal involving Mr. Sisi’s inner circle.

Mada Masr reporters say the need for solid journalism is more important than their own personal feelings, no matter how great their outrage.

Mr. Hamama and the Mada Masr staff were drawn to journalism during the heady days of the Arab Spring. But while the turbulent post-revolutionary period and 2013 military coup led others to give up or emigrate, the Mada Masr staff became convinced that Egypt needed independent journalism more than ever.

To survive amid widespread arrests of journalists and the nationalization of most private media, they adapt.

When the government blocked their site, they provided readers with work-arounds. When authorities pressured advertisers to withdraw funding, they offered “memberships” to readers, inviting them to support the news while forging a community of concerned Egyptians.

Catch and release

Mada Masr journalists held to the belief that they were too small to be worth jailing. But in late November, police stormed the paper and drove off with chief editor Lina Atallah, Mr. Hamama, and reporter Rana Mamdouh.

The three were convinced they would not see the light of day for a year, if ever. Since 2014, authorities have routinely subjected detainees to months or years of pretrial detentions. And due to crowding and poor conditions, a prison term can be a death sentence in Egypt.

Mada’s readers alerted Western reporters in Cairo. They called their embassies, and diplomats queried the Interior Ministry. After 90 minutes, a “miracle,” in Mr. Hamama’s word: The police car returned and dropped the reporters at the office. They were released without charge.

Two days later, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo condemned the raid in a rare public rebuke of the Sisi regime.

The cost-benefit for the government shifted; arresting Mada’s reporters and subjecting them to years in prison is more trouble than it’s worth for now.

But what if the government’s thinking changes again?

“That is what we are all wondering,” Mr. Hamama says, sitting on the iron balcony of Mada’s office. “We don’t know if or when the regime will change its calculations and we will be arrested for good.”

He shrugs. “So we might as well continue.”