Fashion – not disability – defines this young entrepreneur’s future

Loading...

| Darien, Ga.

Will Howell doesn’t wear a tie every day, but he loves nothing so much as getting dressed to the nines for church or a wedding or, really, for any occasion at all.

He is the epitome of a Southern gentleman, shaking hands with all comers, hugging them, cheek-pecking, and generally charming the pants off them, sharply dressed in threads by Nautica and Brooks Brothers and sporting a jaunty bowtie.

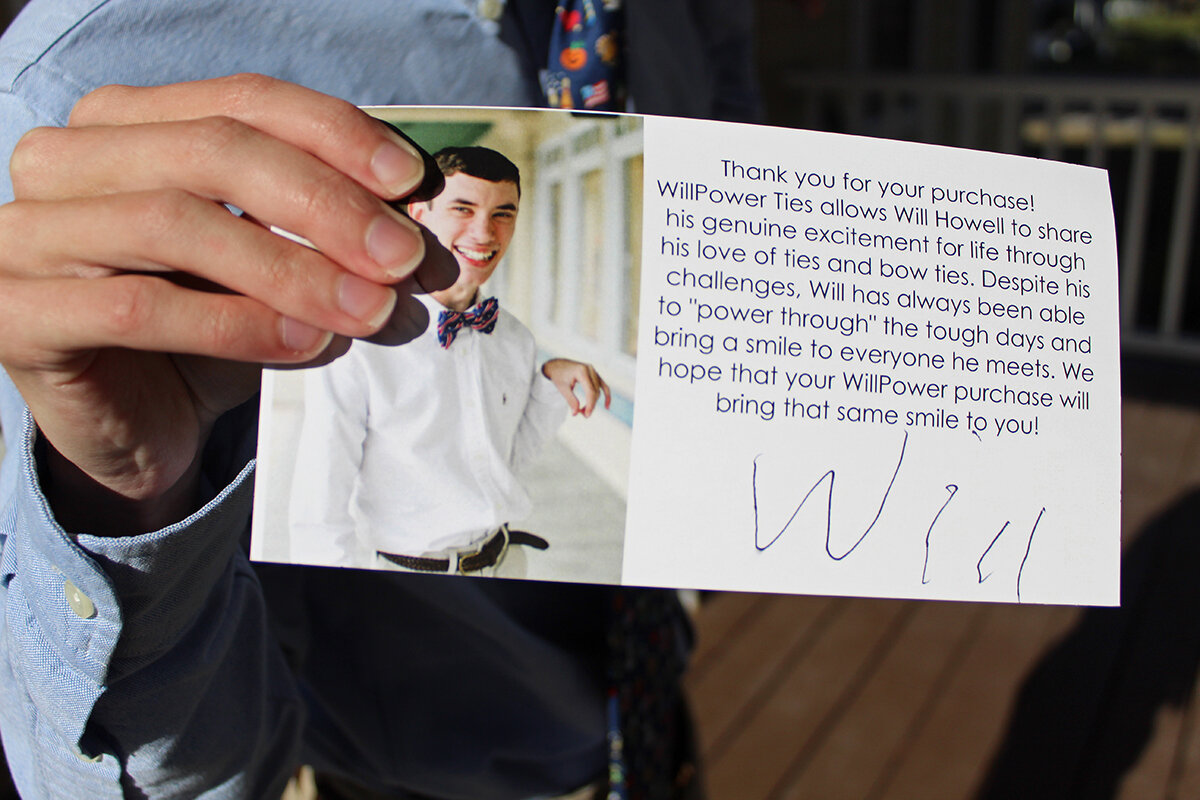

Mr. Howell, who is 20, has cerebral palsy. But his megawatt smile hints at unique talents and abilities that he has put to profitable use. In the face of daunting odds, but fueled by his keen fashion sense, the young Georgian and his father launched WillPower Ties this fall, selling Mr. Howell’s favorite neckwear.

Why We Wrote This

Can stigma have a silver lining? Exclusion can compel us to design our own doors when other doors close. Consider Americans with disabilities like Will Howell, who find not just income, but independence, in self-employment.

“It’s been really cool,” he says, pointing to recent orders from states as distant as California and Texas for ties in styles such as “Rock the Vote” (decorated with elephants, donkeys, and “Vote” buttons) and “Chick Magnet” (that one features fluffy chicks, magnets, and bolts of lightning).

Just before Christmas, Mr. Howell is wearing the multiple hats of an internet shopkeeper at his family’s modest home in this historic fishing village off Doboy Sound: founder, model, PR guy, packing clerk, and, finally, delivery man, hauling packages over to the post office on a custom trike.

Mr. Howell is part of a nascent but notable rise in the ranks of young entrepreneurs with disabilities, says Cary Griffin, a leading expert on self-employment for people with disabilities. As they lend their names, faces, ideas, and designs to businesses selling everything from popcorn to socks, these entrepreneurs are launching companies that serve to unleash their human potential, disdaining pity in favor of profit.

A new purpose

“Since he was an infant, Will has been significantly limited in his physical abilities, but he has more than made up for that in his level of enthusiasm and happiness and desire to be part of this world,” says Dr. Ben Spitalnick, Mr. Howell’s pediatrician.

Those qualities likely would not have been enough to secure him a job. Barely a third of the 24 million Americans diagnosed with severe mental and physical disabilities part time.¬Ý¬Ý

“People like him stay in school until they’re 20 or 21, and then they age out and they don’t know what to do. And for all the development and job skills resources that are out there, [agencies] can’t create jobs,” Dr. Spitalnick says.

But Mr. Howell’s attributes are well-suited to doing his own thing in his own business.

“This family created a job, a company,” Dr. Spitalnick says. “It’s given them a new direction and it’s given Will a new purpose.”

The inspiration for WillPower Ties is John’s Crazy Socks – founded by John Cronin, who has Down syndrome, and his father, Mark – which offers “socks, socks and more socks” on the web. Its success launched the pair on a speaking tour, which recently took them to Savannah, Georgia, near Mr. Howell’s home.

Hearing about the talk, “we immediately started thinking, ‘what could Will do?’” says Melanie Howell, his mother. “We landed on his love of ties.” Her husband, Carey, sold his convenience store to go into business with his son.

Decades of advocacy have done little to dent disabled unemployment rates in the United States. People with disabilities face barriers ranging from transport difficulties to government-imposed income ceilings if they receive Medicaid or supplemental Social Security benefits. Poverty and low self-esteem are common, according to the Institute on Disability.

“There’s a reason why people with disabilities have such a hard time finding a job,” says Megan Henly, project director for the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire, in Durham. “Someone like [Mr. Howell] might have a good day or a bad day. It’s hard to find transportation.

“Self-employment seems like a way around that,” she says. “And the internet has created this ability to interact with the public that didn’t exist even 10 years ago.”

In 2011, a higher share of workers with disabilities¬Ý than those without disabilities ‚Äì 11.8% versus 6.6% ‚Äì piggybacking on decades of pioneering work promoting self-employment among the former group.¬Ý

Many of them also benefit from a Department of Labor program called Employment First, which stresses that ‚Äúyou have to adapt the environment to fit the person, not the other way around,‚Äù says Mr. Griffin, the co-author of ‚ÄúMaking Self-Employment Work for People with Disabilities.‚Äù¬Ý

“There are unlimited ways to make a living in the world, but we tend to think of just a few things for people with intellectual disabilities: Clean the dishes at the humane society, work at the food co-op, work at McDonald’s – and then we’re out of ideas,” says Mr. Griffin.

It takes imagination to go beyond that, he says. “Sometimes we have to reframe” the challenge, Mr. Griffin says. If someone is fixated on railroad trains, for example, “let’s not try to get you to like trains less, which is what tends to happen.” Instead, think how that trait might be put to use. “Let’s move toward transportation,” he suggests.

“Behavior is the No. 1 thing to keep you out of the workforce,” he says. So why not ask, “Where does this behavior make sense?”

“Terrifying, Mom?”

The trend is gathering momentum at a time when people with disabilities are receiving more sympathetic treatment in popular culture.

The power of the media to shape attitudes is critical to encouraging a fresh approach to employment, says Susan Dooha, executive director of the Center for Independence of the Disabled in New York.

“People with disabilities are perfectly employable, and the reason they are not employed is stigma,” says Ms. Dooha, who herself has a disability. It’s “important to see us as contributors, and not needing to be inspirational and having to live up to an impossible stereotype, but also not being seen as a pitiable object of charity,” she adds.

Ms. Howell, a fifth grade teacher, says she long dreaded the moment her son faced adulthood.

“It’s been terrifying,” she says.

Although he tends to defer to his parents during conversations, Mr. Howell interrupts: “Terrifying, Mom?”

“Yes, it’s terrifying because I couldn’t be sure what would happen to you,” she says.

Ms. Howell chafed at the comfort that her late father-in-law, Archie Howell, tried to offer her. “You know, Will is going to find his way,” he would say.

“That used to make me mad,” Ms. Howell recalls. “But to see it now coming true has been divine.”

It was Ms. Howell who pushed to open the store by Nov. 1, which at times seemed impossible. Nov. 1 was ‚ÄúPapa Howell‚Äôs birthday,‚Äù explains her husband. ‚ÄúPapa Howell,‚Äù Will chimes.¬Ý

WillPower Ties is donating 5% of profits to AMBUCS, which provides free custom bikes to Americans with physical limitations. The ties are flying out the door, and the company has just launched its own custom brand with a tie that the young entrepreneur designed to draw attention to cerebral palsy.

“They are hitting it like rock stars,” says Dr. Spitalnick. “Will is enjoying it, it has brought his family together, and they’ve succeeded in not just a successful business launch but a successful launch of the next phase of Will’s life.”