In Kenya, humanitarian workers ponder life after USAID

Loading...

| Nairobi, Kenya

Two weeks ago, we told the story of a former USAID employee making sense of his future in Donald Trump's America. Today, we are looking at the experience of former American aid workers in Kenya grappling with the same kinds of questions.

A self-described jaded New Yorker, Felicia never imagined working for the U.S. government. A nurse with a master’s degree in international affairs, she spent nearly a decade with nonprofits across Africa focused on HIV, mostly at grassroots nonprofits.

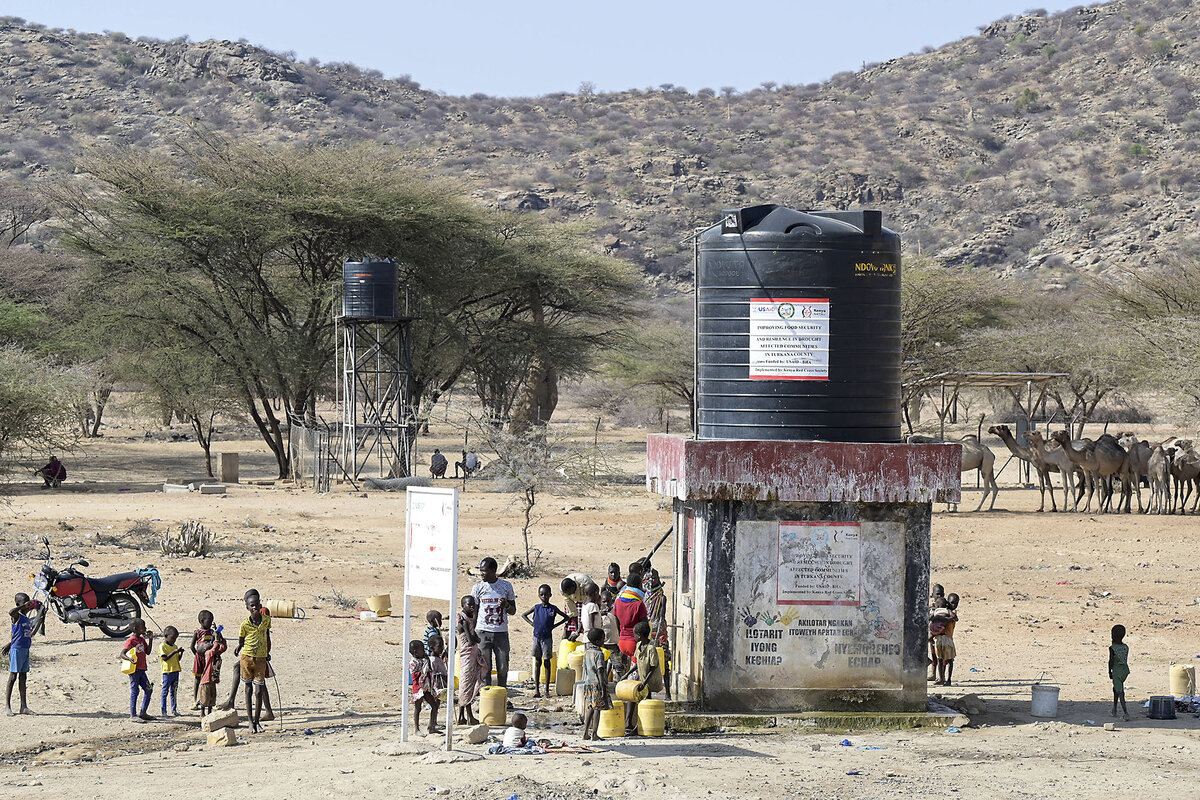

But it became clear to her that one agency was outpacing all the rest, especially when it came to public health. Its logo could be found in the most remote places, plastered on the walls of clinics and boxes of medical supplies. And it was funded by the country she had left behind.

Why We Wrote This

Until recently, USAID was one of the largest aid agencies on the planet. Now, it is a whisper of its former self, and in Kenya, former employees are grappling not only with their personal future, but also their country's.

In 2021, she took a large pay cut to become a foreign service officer, responsible for distributing American generosity abroad.

“Coming to work for USAID was the first thing that ever made me feel really proud to be an American,” says Felicia, one of two USAID workers featured in this story who asked that only their first names be used because their severance packages are still being finalized.

In January, the Trump administration abruptly froze nearly all American foreign aid. Humanitarian programs around the world lurched to a halt. Felicia was fired. According to one estimate, , including 19,000 Americans, have lost their jobs either with the U.S. Agency for International Development, as USAID is formally known, or its contractors.

And for many of the Americans in particular, the transition is more than professional. It means rethinking their entire relationship to their homeland.

“I’m ashamed of how my government has behaved,” says Felicia. “This is not a job. This is my life’s work.”

Coming home to a foreign country

International moves are nothing new for Josh, who has spent the past two decades working with the Peace Corps and a variety of nonprofits. He has moved countries eight times since 2001, mostly in Latin America. Last July, he started his first tour with USAID, bringing his wife and two daughters to Kenya.

After he received his termination letter in March, Josh and his wife made the decision to move again. This time they are headed to a country that feels particularly foreign to all of them: the United States.

“It’s almost like I’m going on a Peace Corps service to my home country,” he says.

Josh doesn't know how that country will receive him. The president has said his work is useless and wasteful, and those around the president have called workers like him and his colleagues “” and “.”

Preparing to return to the Ohio town where he grew up, he tries to put himself in the shoes of his neighbors-to-be. He understands why Americans struggling with debt or working multiple jobs would cast doubt on the government sending billions of dollars in aid overseas each year.

However, studies have consistently shown that Americans significantly overestimate foreign aid spending, believing on average it of the federal budget, when it actually comprises less than 1%. And Josh says he sees in foreign aid a fundamentally American spirit.

“If I have a huge plate of food, and you're sitting over there with a toothpick and a glass of water, I'm going to ask, ‘Can I share my food with you?’” he says.

An uncertain future

While USAID's fate has left aid workers reeling, some argue that this could also be a learning moment for the sector, which has long been criticized for spending too much money on Western staff and imported supplies and too little on people in need.

Some pruning is not necessarily a bad thing, says Tracy Kijewski-Correa, director of the Pulte Institute for Global Development at the University of Notre Dame. “If we as development professionals do a good job, we eventually put ourselves out of business.”

Her own institute abruptly lost millions in funding, and she says they were forced to terminate 12 projects in 30 countries in a span of just two days, making it difficult to wind down their work responsibly.

“It should have been a ramp down,” she says.

Felicia says one of the hardest things she has had to do is close out projects with the grassroots charities that USAID funded. She has found it heart-wrenching to tell her Kenyan counterparts that her government no longer supports their work.

“Why would anyone ever trust us to do anything?” she asks. “Why would anyone want to work for us?”

In Nairobi, the USAID shutdown has had a ripple effect. Home prices are already in the city’s upscale suburbs, normally in high demand among development professionals.

For Felicia, the sudden departures of friends and colleagues are still hard to grasp. When she chose to work for the government, she knew she would have to implement policies she sometimes disagreed with.

“But nobody saw this coming, to be so disrespected and derided by our own government,” she says.

Now, she wonders what she will do next. The job market has been flooded with laid-off USAID workers like her. She says the last job she applied for sent a rejection note explaining that it had received over a thousand applications.

As Felicia continues her search, she has begun volunteering twice a week at a small health clinic in Nairobi. She says it helps her maintain a sense of purpose as she ponders the future.

But one thing is clear. Felicia is not going back to the United States. She will stay here, she says, and continue the work her government once did.