His USAID career over, one worker wonders if he can still serve his country

Loading...

| Minneapolis

After rifling through a kitchen cabinet to find a hole punch, William Bradley sat down at his dining room table Friday morning in Minneapolis with a cup of coffee and the diplomatic passport that heãs had for roughly two decades. As instructed, he punched two holes on the bottom. He took a picture of those holes with his cellphone. Then, he emailed the government proof that his career was over.

It was at this table five months ago that Mr. Bradley learned from a cable TV news report that he and at the United States Agency for International Development were losing their jobs. For the past five months heãs felt scared. He was three years away from retirement and the pension his family has been counting on. For five months heãs felt guilty. When the news broke, Mr. Bradley had just finished onboarding 21 new USAID employees who had quit other jobs to serve America. For five months heãs been angry. One day, he walked out his front door and got in his VW camper van, closed the door, and screamed.

And, against his better judgment, for five months heãs been in denial ã waiting until the day the photo proof was actually due to pull out his hole punch. A small part of him had hoped that his government would realize, at some point, that it needed him.

Why We Wrote This

Five months after the Trump administration announced it was gutting USAID, most workers got their final paychecks this week. Many have been struggling to find a sense of purpose as well as financial stability. The Monitor followed one veteran worker as he tried to figure out his next steps.

But July 1 is the official , putting some USAID functions under the purview of the State Department while terminating the rest. It is also the last day on the payroll for USAID employees like Mr. Bradley.

Now, after a liminal period of judicial restraining orders, reversals, and much waiting, thousands of USAID workers are having to begin a new chapter. For many ã along with other federal workers fired at the hands of President Donald Trumpãs Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE ã that means figuring out a new career in a flooded job market. Some are considering running for political office. Others are suing the government they used to serve.

Overall, at least 58,000 federal workers have been fired since President Trump took office in January, promising to ãã and hold a workforce to account. Another 76,000 have accepted buyouts.

Few agencies, however, have received the kind of vitriol leveled at USAID. Mr. Trump has called USAID employees ãã who have stolen ã.ã Elon Musk, the worldãs richest man, who headed DOGEãs efforts for months, celebrated ãã while helping to cut more than 99% of the agencyãs staff.

One challenge for many of these former employees is reconciling how they see themselves ã as loyal Americans who have dedicated their lives to their nation ã with the derogatory statements from their president and his administration.

Mr. Bradley has always considered himself a patriot, someone who serves his country.

Now he looks to his family, sitting around the dining room table, with a pressing question: ãShould I run for Congress?ã

ãNo,ã says Hawa, his daughter, who just graduated from middle school.

ãI think itãs wiser to take a job,ã says his son, James, who will begin a Ph.D. program in chemistry at the University of Minnesota this fall but is worried about the apartment lease he just signed, given the Trump administrationãs cuts to science funding.

ãWhy do you want to batter yourself again?ã asks his wife, Azarath. ãYour government should protect you, not hurt you.ã

A life of foreign service assignments

Over the 17 years he spent as an officer in the United States Agency for International Development, Mr. Bradleyãs life was a series of assignments: Build latrines in Benin. Help farmers amid warãs wreckage in Afghanistan. Oversee agriculture projects in Cambodia, Guinea, and Senegal.

He sometimes worried that he was putting his family through too much for the sake of his job. He remembers watching his children get their temperature checked before school every morning when they were in Guinea during the Ebola crisis. He recalls how his wife was so upset to leave Minneapolis for Senegal a decade ago that when the movers arrived, nothing was packed. James was unhappy in Guinea after leaving all of his friends in Cambodia and chose to finish junior high at a boarding school in Minneapolis. Hawa canãt decide what country is home, after living in Minneapolis for three years and Senegal for five years before that.

Mr. Bradley always knew that private sector jobs in the mining industry, where he had started his career in Utah, paid double what he made with USAID. But whenever he considered quitting government service, he thought about how he made a difference in peopleãs lives as a representative of the United States. And he knew that even though he was making a lower salary now, he would have a federal pension later.

When he turned on his work computer Friday so it could be remotely wiped by one of the few remaining USAID employees, he found himself reviewing some old documents, like one he had saved about the Foreign Service Pension System.

It confirmed the numbers he had already triple-checked on an Excel spreadsheet heãd made. In three years, on July 3, 2028, Mr. Bradley would have had 20 years of qualifying service and been eligible for $4,274.82 a month before taxes and insurance.

ãWe had a plan,ã Mr. Bradley says to Azarath, as well as himself. She hacks a raw chicken in the kitchen and packs cornmeal into balls for amiwo, a dish from her native Benin.

It was in Benin, when Mr. Bradley was serving in the Peace Corps, that he met Azarath. He would spend hours traveling to see her on the weekends. A few years later, Mr. Bradleyãs first paycheck from USAID went to a Beninese hospital to pay for the birth of their first child, James. When Mr. Bradley was assigned to a new project in Afghanistan and his young family couldnãt come, he bought a house for them sight unseen in Minneapolis, where Azarathãs new mother-in-law taught her how to ride the bus to her English classes, with James slung on her back.

She sighs. Adjusting to America alone with her baby, with her husband living abroad, was hard. But these past few months have been harder. When James graduated from college this spring, she wondered if it was OK to buy balloons since his dad had just lost his job. She wonders now if she should quit culinary school and find work herself, even though her goals (medium term, begin selling signature West African dishes locally; long term, own a restaurant in Minneapolis) remain tacked on the kitchen wall.

They had thought when Mr. Bradley retired he could help his wife open a restaurant, and she could finally launch her own career after so many years of supporting his. But now, Hawa was asking her mom if they would have to move again. Mrs. Bradley didnãt know how to answer.

What comes next when USAID closes

The rumors and news reports became real for Mr. Bradley on Feb. 4, when an email with the subject line ãThe Path Forwardã arrived in his inbox, saying ãall USAID direct hire personnel will be placed on administrative leave globally,ã except for a few mission-critical employees. Later that week, Mr. Bradley watched on television as a man in a cherry picker pried the letters spelling ãU.S. Agency for International Developmentã off the Ronald Reagan building in Washington. He remembers being surprised at how easily they came off.

President John F. Kennedy created the agency during the Cold War in 1961 to compete with Soviet influence abroad. In the decades since, USAID grew into one of the largest aid organizations in the world, . Still, at the time of its gutting, it accounted for , and a smaller share of gross domestic product than what other leading industrialized nations spend on foreign aid.

In those first weeks of February, as the agency was dismantled, protesters in Washington showed up to support what many saw as the pillar of American soft power. But the public outcry soon dwindled, even as the courts issued restraining orders and in some cases reversals. In late March, Mr. Bradley received a reduction in force (RIF) email telling him his pay would stop on July 1.

Mr. Bradley, along with more than 50 USAID colleagues, has filed a lawsuit alleging they were illegally terminated for political reasons. He has also joined more than 200 former USAID workers planning to file claims of age discrimination, because the RIF will affect their retirement benefits.

Yet even as he fights the government and feels deeply that it has broken its promises to him, Mr. Bradley also keeps thinking about other ways to serve. In particular, he wonders if running for office could allow him to keep his promise to protect the Constitution against any enemies ã foreign or domestic.

ãMy heartãs really telling me to run,ã Mr. Bradley tells his family. ãSomebody has to hold them to account.ã

So, on a Saturday morning in late June, as an excessive heat warning blanketed Minneapolis, he found himself driving north on Interstate 94, hugging the Mississippi River in his yellow 1996 Ford F250.

He had spent the past few weeks tackling projects around the house, like replacing the brakes in his truck. He also did some things he never expected ã like reaching out to a local contact for the Democratic Party. When he spoke to Tamara Polzin about his interest in possibly running for office, she invited Mr. Bradley to come to a forum in Blaine for potential congressional candidates.

He turns up the truckãs radio dial, as a public policy expert on NPR explains the importance of keeping federal workers . Mr. Bradley turns the radio back down. After 17 years he had experience, but hadnãt he also been loyal?

New administrations always bring new priorities and new marching orders, and he believed his job was to follow them like a soldier. A few years after President George W. Bush announced the military invasion of Afghanistan, Mr. Bradley was dispatched to the Badakhshan Province to manage a $57 million contract helping locals find alternative crops to opium. At the end of President Barack Obamaãs second term, he was sent to West Africa to help farmers in Guinea and Sierra Leone recover from the Ebola outbreak.

Although he was disappointed when the first Trump administration cut that projectãs funding, he accepted it as part of the job. He had hoped that Mr. Trump in his second term would see ways to use the organization for his own objectives, like jump-starting job opportunities abroad so fewer foreigners would try to immigrate to America illegally.

But even if Mr. Trump couldnãt see value in USAID, Mr. Bradley believes other politicians ã like Rep. Tom Emmer, the GOP majority whip whose deep red district covers the northern and western outskirts of Minneapolisô ã should have.

ãAre you running or watching?ã

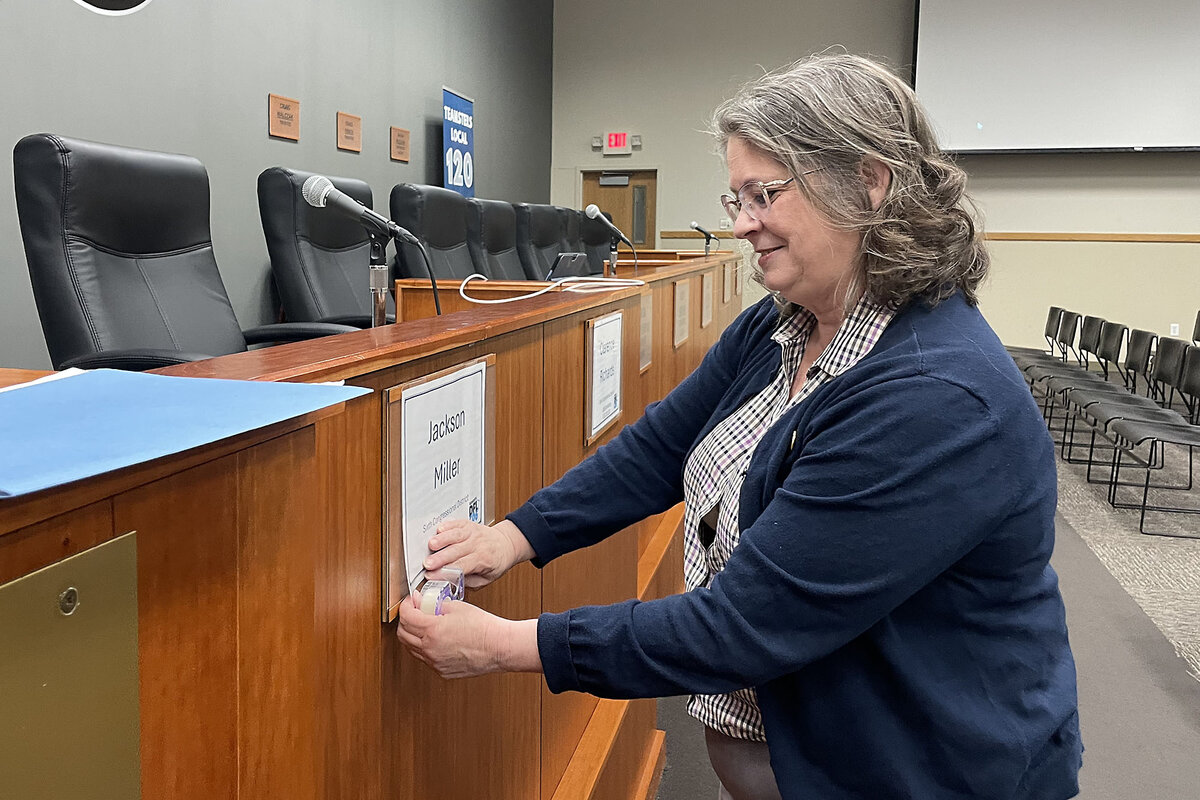

Walking into the Teamsters Union Hall, he finds Ms. Polzin taping participantsã name tags on the stage. As a local Democratic chair, Ms. Polzin has struggled in past cycles to find a single Democrat willing to run in the 6th district, one of the most Republican in the state. But now, more than a year and a half out from the 2026 midterms, she already has 13 interested candidates, including Mr. Bradley and five others taking the stage today to practice speaking in front of a friendly audience.

ãThe excitement in the district is more than Iãve ever seen,ã says Ms. Polzin. People have been protesting every week, she says, angry about deportations and cuts to Veterans Affairs, despite Mr. Emmerãs claims that the local VA has only dismissed seven probationary employees. A new energy was injected into those protests, she adds, after the recent shootings of two Democratic state lawmakers.

Mr. Bradley takes a seat in the second row, as other observers fill in behind him.

ãAre you running or watching?ã a man behind him asks.

ãJust watching,ã Mr. Bradley answers.

The event begins with a moment of silence for state Rep. Melissa Hortman, who was killed along with her husband on June 14 in their home just eight miles away. ãWeãre going to forge ahead and weãre going to show that they canãt deter us and that the best way to honor the memory of Melissa and Mark is to have the seeds of democracy sprouting up all throughout the 6th Congressional District,ã says state Rep. Matt Norris, the eventãs moderator.

Mr. Norris asks the five potential Democratic candidates questions about infrastructure, unions, science research, and Social Security. Throughout, Mr. Bradley takes notes on 3-by-5 index cards. He stays silent for the 90-minute event until the end, when one candidate, a flight attendant, talks about feeling an ãethical compulsionã to run for office.

ãThatãs right,ã he says quietly. ãThatãs right.ã

By Monday morning, though, that compulsion to run feels more like an impractical whim. For his familyãs sake, he decides he probably needs to focus on finding a private-sector job.

He spends his last days as a USAID employee offering follow-up advice to the other candidates who participated in Ms. Polzinãs forum and speaking with a political action committee focused on supporting foreign assistance. He gets some satisfaction picturing a ãdiasporaã of USAID employees fanning out across the world ã bringing their expertise into the realm of politics and private companies. But at the same time, he canãt help but think about what his country has lost.

ãWeãre an asset for the people of the United States,ã he says wistfully. ãWhen we go out, itãs from the American people.ã

His wife still remembers when USAID came to her village. Seeing those American flags gave her ã she stops to ask Mr. Bradley the word for what happened to her arms. ãGoosebumps,ã he says, and she nods.

ãThey represent America doing good,ã she echoes. ãThat they are here to help.ã