Why one Arkansas town has pinned its hopes on a teen mayor

Loading...

| Earle, Ark.

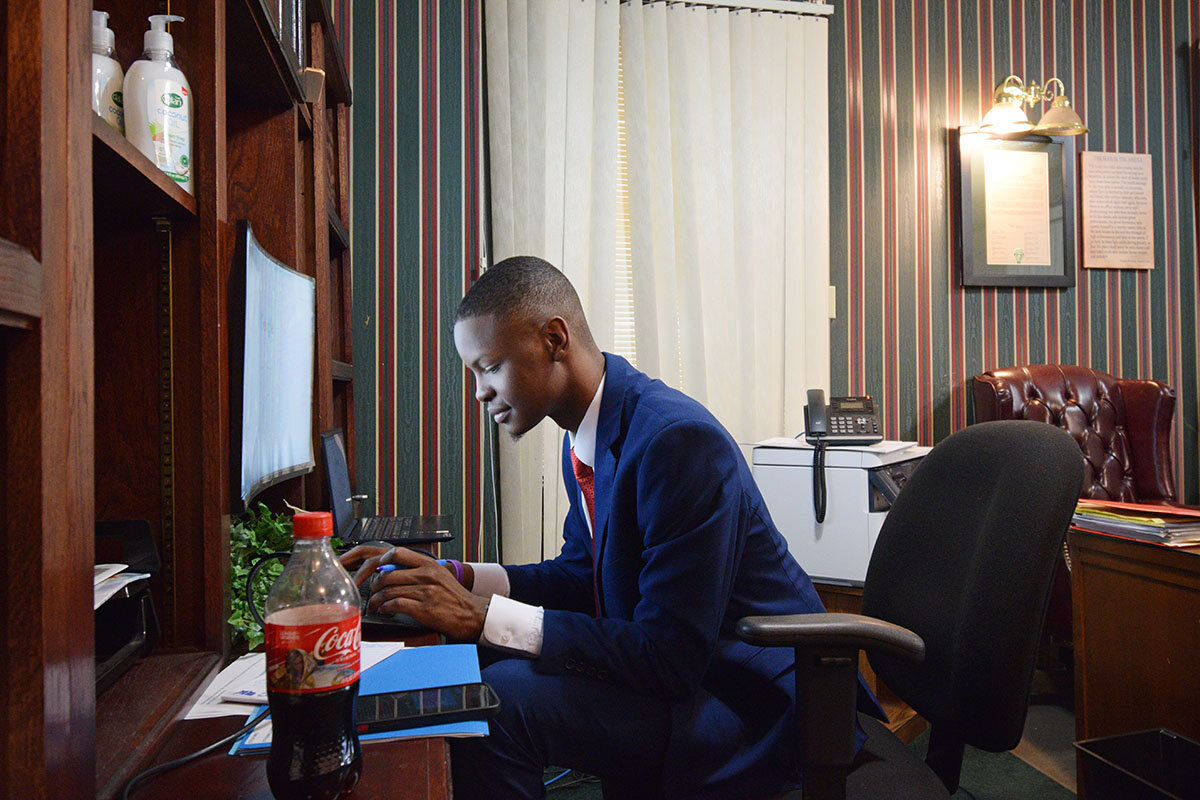

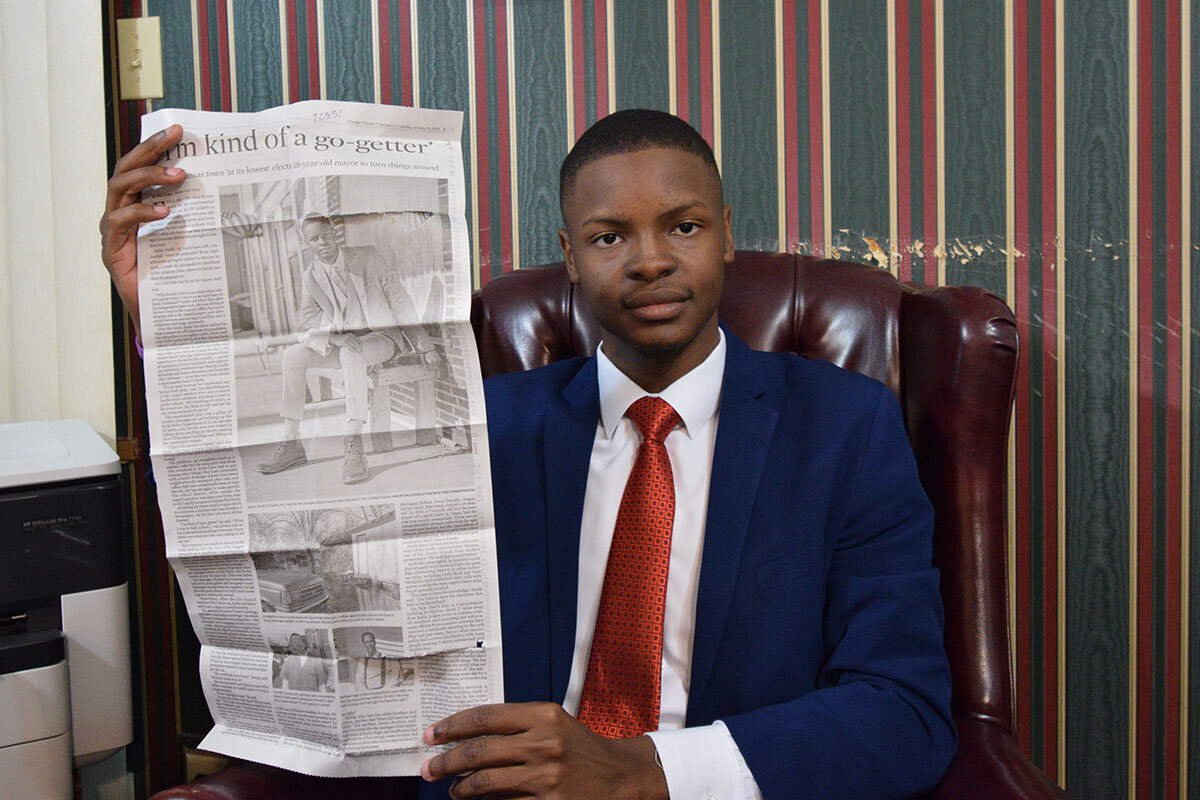

Many teenagers consider their wardrobes a statement of their identity. For 18-year-old Jaylen Smith, that means a suit instead of jeans and a backpack. Today, the new mayor of Earle, Arkansas, has dressed with special care: a navy two-piece suit, crisp white shirt, and brown dress boots. His tie is red.Őż

Tonight, he will call the City Council to order for the first time as mayor. He‚Äôs also heading into Memphis ‚Äď 30 miles away ‚Äď to buy his own car, a Nissan Altima.

‚ÄúIf you want to get somewhere, you have to act and dress like it,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúAnd that‚Äôs what I did.‚ÄĚ

Why We Wrote This

Generation Z is stepping up in national politics and state legislature ‚Äď and in this small Arkansas town. Instead of heading away to college, 18-year-old Jaylen Smith ran for mayor, and won.

If he‚Äôs nervous about his big speech, it doesn‚Äôt showŐżas he does his job from an office with decor from the mid-20th century, from the burgundy-and-green striped wallpaper to the fake fruit vines wrapped around the brass sconces. The computer on his desk may be the only thing that, like Mr. Smith, hails from the 21st.Őż

He works with his door open to the street, an invitation to his town.Őż

Whether he‚Äôs in his office, on the road, or stopping at a parking lot to pick up chicken salad ‚Äď and pause for a selfie with the guy selling itŐż ‚Äď Mr. Smith is always on the phone. Dialing a number, he talks to a woman whose house just burned down. ‚ÄúIs there anything we can do for you,‚ÄĚ he asks. He listens to her response, nodding, and promises he‚Äôll call the Red Cross.

He‚Äôs not the first teen mayor in the U.S. ‚Äď Hillsdale, Michigan; Mount Carbon, Pennsylvania; and Roland, Iowa, are among cities that elected leaders right out of high school. But Mr. Smith is the youngest Black mayor in the country, according to the U.S. Conference of Mayors. He won in a runoff election, pledging to staff police 24 hours a day, tear down derelict buildings, and bring back the supermarket that closed down a few years back.

Driving past Crawfordsville, a town about 15 minutes from Earle, he explains thatŐżhis parents ‚Äď as well as grandparents and cousins ‚Äď lived there before moving to Earle, where he grew up, in 2000. Mr. Smith was born five years later.

Mr. Smith graduated from Earle High School in 2022. Instead of packing for college and leaving, he spent the rest of the year campaigning door to door and shadowing mayors around the state.

Perhaps more notable than Mr. Smith‚Äôs age is his choice not to leave Earle. As he tells Christopher Conway, his former high school counselor, ‚ÄúI always wanted to change my community before moving on to my next phase of life,‚ÄĚ he says.

‚ÄúThat‚Äôs right,‚ÄĚ agrees Mr. Conway. ‚ÄúYour goal is always to build up Earle.‚ÄĚ

Earle, Arkansas, population 1,800, may seem frozen in time by a lack of money and a declining population. The sense of community buy-in and optimism is clear in the halls of the elementary and high schools, and the well-attended City Council meeting ‚Äď with an agenda including reports from the police chief and the water and sanitation department, and a debate about zoning.Őż

Tucked on the side of Highway 64, Earle boasts three dollar stores and two schools, and a small grocery store that‚Äôs been around since 1945. The number of abandoned buildings suggest that Earle has seen better days ‚Äď that Mayor Smith is pledging to revive.Őż

Earle rose out of the post-Civil War timber boom that gave life to so many other small towns dotted along Southern railroads. Today, the town is majority Black. But its painful history includes lynchings and a race riot over school conditions, not to mention its namesake, landowner Josiah Francis Earle, who was active in the Ku Klux Klan.

Eugene Richards, a photographer, writer, and filmmaker, found himself in Earle in the late 1960s as a member of Volunteers in Service to America. At the time, Earle was separated into white and Black, he says, ‚Äúdivided by the classic railroad tracks.‚ÄĚ

Mr. Richards and several VISTA volunteers helped start a paper, Many Voices, which reported on Black political action and the Ku Klux Klan. He was friends with the Rev. Ezra Greer and his wife, Jackie Greer, civil rights activists who led a march protesting segregated schools in 1970. When the marchers were confronted by an angry white crowd, five Black marchers were wounded ‚Äď including two women who were shot.

After that day, Mr. Richards says, ‚ÄúTime went on and things slowly changed.‚ÄĚ

Mr. Richards, who compiled photos and interviews for a 2020 book about the town, says that while the violence of segregation may be in the past, Earle faces new challenges.

‚ÄúThere‚Äôs a weariness ‚Äď the town is going down very fast,‚ÄĚ he says.

As student government president for his last three years at Earle High School, Mr. Smith implemented tutoring programs and an advocacy committee for students with learning disabilities. He was also a student advocate for special education students, and dealt with his own learning disability while in school. Those activities taught him how to get resources from the state, he says. After a visit to Washington, D.C., for a mayoral conference, he’s optimistic about receiving more federal grants as well.

Mr. Smith is part of a growing number of civically engaged members of Generation Z, says Layla Zaidane, president and CEO of the Millennial Action Project.

In the past year, the number of millennials running for office increased by about 57%, says Ms. Zaidane. The number in Generation Z nearly tripled.Őż

‚ÄúYoung people are choosing to run towards our political system and actually [put] their own hat in the ring,‚ÄĚ she says, chalking that impetus up to the ‚Äútwin forces of frustration that things aren‚Äôt better and a sense of agency that they can make it better.‚ÄĚ

Between learning the ropes of public office and taking a college course online as he pursues his degree ‚Äď one class at a time for now ‚Äď Mr. Smith doesn‚Äôt have much free time.

His phone rings again. This is the part of the job he doesn‚Äôt like: being pressured for favors. In this case, he stands his ground over the open clerk position. Every applicant has to turn in an application, he says firmly. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm not going to hunt it down.‚ÄĚ

Off the phone, he runs down his goals as mayor. He wants to improve public safety, including fully staffing the police department, currently at two full-time and four part-time officers; set up public transportation; and tear down those abandoned houses.

He‚Äôs already spoken with a local business that has agreed to help demolish houses, and he‚Äôs confident he‚Äôll find resources to achieve the rest of his goals. ‚ÄúThey‚Äôre there,‚ÄĚ he says.

Back in Earle, he turns to answering correspondence, finding grants to apply for, and, of course, picking up the steady stream of phone calls on both of his cellphones. He starts working on another ‚Äúfirst‚ÄĚ: filling out a funeral resolution. After searching online to no avail, he picks up his phone and dials. ‚ÄúHey Pop,‚ÄĚ he says, taking a drink of Coke. ‚ÄúWhat did you tell me I need for a funeral resolution?‚ÄĚ

That done, Mr. Smith turns to the next task. He asks a friend who just walked in, Lacordo Hemphill, for a favor. Can he run out and get him some Ritz crackers and a bag of spicy Doritos to eat with his chicken salad?

Mr. Smith may have the job and suit, but he still has the lankiness and appetite of a teenage boy, subsisting on chips and soda as he sorts through city paperwork and responds with patience to citizens’ complaints and concerns.

He pivots back to his computer monitor, as gospel music plays in the background.

While Mr. Smith, a Democrat, aspires to higher office, he says he isn‚Äôt focused on party politics. He attends local Democratic and Republican party meetings to ‚Äúsee how they both do,‚ÄĚ he says.

Mr. Smith opens an envelope and a check falls out of the card inside. He dusts chip dust from his fingers and makes another call: ‚ÄúWhat do I need to do with checks that come in the mail?‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúI can‚Äôt accept money as an elected official,‚ÄĚ he explains after. ‚ÄúBut I can donate it to the city.‚ÄĚ

Donald Russell, a retired truck driver, was skeptical when Mr. Smith announced his campaign. But after getting to know him, he has ‚Äúhigh hopes.‚ÄĚ

And Mr. Smith ‚Äúhas a lot of community support,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúThis is his city.‚ÄĚ

His friend Mr. Hemphill says he‚Äôs excited to see a young person in local politics ‚Äď maybe even more so than Mr. Smith himself. Now he‚Äôs more inclined to vote and go to community meetings, he says.

Outside, Mr. Smith can‚Äôt walk down the street without bumping into someone who ‚Äď even if they‚Äôre raising a concern ‚Äď can‚Äôt help hugging him, or telling him how proud they are of him, ‚ÄúMr. Mayor,‚ÄĚ the ‚Äúgood kid.‚ÄĚ

Thirty minutes before the council meeting, Mr. Smith stands up, puts on his suit jacket, locks the door, and crosses the street to the council chamber. People trickle in after him ‚Äď one asks to take a photo together. Every seat is full, and residents are standing at the back. Mr. Smith opens the meeting, occasionally leaning over to check next steps and procedure with his more experienced companions. Then he stands to deliver his speech, announcing his goals to fully staff all police shifts and institute a neighborhood watch program.

He ends with a quote from the Bible to nods, murmurs of approval, and applause from the room: ‚ÄúLet us not weary in doing well, for a new season we shall reap.‚ÄĚŐż

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify that Mr. Richards helped cofound the newspaper Many Voices.