Challenge to US sovereignty? In polls public accepts constraints on power.

Loading...

| Washington

National security adviser John Bolton’s vigorous defense Monday of national sovereignty in the face of what he views as globalism run amok was enthusiastically received by his immediate audience, the Washington-based Federalist Society.

Ambassador Bolton, the White House’s über nationalist and defender of American hard power, directed warning shots against the International Criminal Court and its purported plans to take up alleged US war crimes in Afghanistan and in third-country “black sites.” Underlying his remarks was what he called President Trump’s reassertion of national sovereignty after years of erosion at the behest of President Obama and other internationalists.

“This administration will fight back to protect American constitutionalism, our sovereignty, and our citizens,” Bolton said. “No committee of foreign nations will tell us how to govern ourselves and defend our freedom.”

Why We Wrote This

To engage in world affairs multilaterally, are Americans willing to give up any sovereignty? For many years, polls have indicated that they are, putting the public consistently at odds with political leaders.

But his conservative audience’s response notwithstanding, US public support for Mr. Trump’s withdrawal from multilateralism and collective action on global issues is less clear.

Indeed, some international affairs experts see a growing gap between the president’s anti-internationalist actions – from withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord, the Iran nuclear deal, and the United Nations Human Rights Council, to funding cuts to UN organizations – and an American public that surveys show favor robust US involvement in addressing global security and economic challenges collectively.

That is not to say Americans favor global government. Yet support for globally addressing issues from security and peace-keeping to the environment and trade seems to have steadily grown.

“If you look at recent polls, you see growing public support for international institutions and multilateral cooperation, even occasionally support for supranational entities or powers,” says Stewart Patrick, director of the Council on Foreign Relations’ program on international institutions and global governance in Washington. “That support does not appear to buy into the absolutist vision of national sovereignty that sees something like the ICC as a grave threat to the US constitution.”

Mr. Patrick – whose 2017 book, “The Sovereignty Wars,” argues that America can both safeguard its national sovereignty and be a robust participant in international institutions and global problem-solving – says most Americans are comfortable with a more elastic conception of national sovereignty that basically says you have to give a little to win a little.

“I think most Americans support the notion that if the US can gain influence by participating in international institutions,” Patrick says, “it’s worth the cost of some measure of freedom of action.”

Patrick worked in the State Department over some of the same years as Bolton, and says he recalls him even then acting to pre-empt any suggestion of US cooperation with the ICC.

Consistent public support

If anything, recent surveys of American attitudes toward international institutions and engagement in global affairs suggest growing support for US involvement, particularly in the UN.

“For a long time the American public has not been on the same page as those in our government and elsewhere with a muscular commitment to national sovereignty,” says Dina Smeltz, senior fellow in public opinion and foreign policy at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. “On the contrary, the public is much more supportive of a range of international institutions and working with other countries to address global issues.”

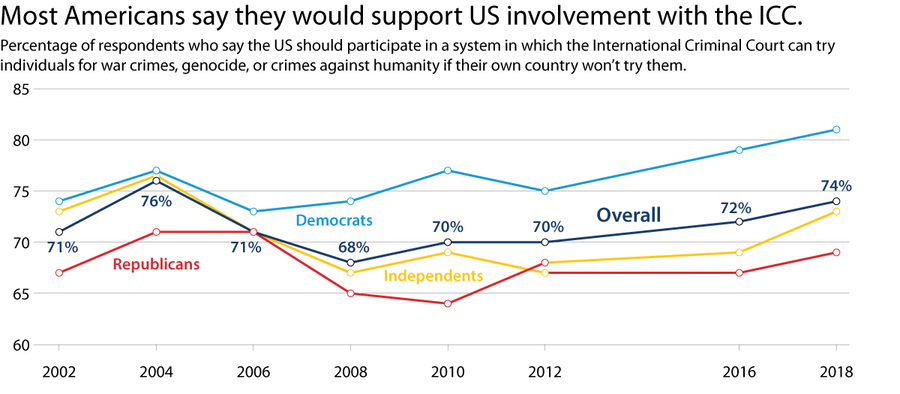

That support extends specifically to the ICC, Ms. Smeltz says. Citing results of the Chicago Council’s annual survey of US attitudes on global affairs, set to be published in October, she says this year’s survey shows a slight upward trend in support for US participation in the ICC, which has hovered around 70 percent for over a decade.

Other surveys confirm this broad support for US global engagement. One study published last year by the Washington-based Pew Research Center showed a “dramatic rise” in positive views of the UN over the last decade.

Whereas fewer than half of Americans (48 percent) had a favorable view of the UN in 2007, that had climbed to nearly two-thirds (64 percent) by mid-2016.

Another survey by the Chicago Council last year found that growing numbers of American young people have a tarnished view of US interventionism, particularly of the military variety. But the survey found that Millennials do not equate their views with isolationism or a US withdrawal from global engagement, but rather with a desire for a more humble and realist US role in the world.

‘Americans govern Americans’

In post-speech remarks to reporters Monday, Bolton asserted that the Trump administration will continue with its absolutist view of national sovereignty – and suggested that the president could take further steps to disentangle the US from supranational restrictions, for example a withdrawal from the World Trade Organization. Trump has threatened to pull out of the WTO.

“The Trump administration view is that Americans govern Americans. How’s that for a radical thought?” quipped the former US ambassador to the UN.

Asked specifically about further steps Trump might take to curtail multilateral institutions such as the WTO and US involvement in them, Bolton said, “concern for national sovereignty is extremely important to the administration. How that plays out in future decisions, I’d rather not forecast,” he added, “but I think it is something that goes directly to democratic theory of who governs.”

In his lengthy comments on the ICC, Bolton said the US position should not be interpreted as opposition to justice for victims of atrocities but rather as adherence to the conviction that perpetrators “should face legitimate, effective, and accountable prosecution for their crimes by sovereign national governments.”

He took US rejection of the ICC further than ever, however, announcing that any effort by the court to investigate American citizens would be met with sanctions, travel restrictions, and even criminal prosecution of ICC judges and prosecutors involved in those investigations.

The US has never been a state party to the ICC, established by the Rome treaty in 1998, although the US did sign the statute establishing the court under President Clinton. Bolton said Monday that President George W. Bush’s 2002 authorization for him as then-undersecretary for arms control and international security to “unsign” the Rome statute was “my happiest day in government.”

In bad company

But other international legal experts and human rights proponents take a dim view of the US action, saying it puts the US in a league with the world’s worst violators of international norms against genocide and other crimes against humanity – many of whom also reject the court’s authority and legitimacy.

“The ICC was created to end impunity for perpetrators of the most heinous crimes, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, when nations are unwilling or unable to prosecute,” said Mark Ellis, executive director of the International Bar Association, in a statement Tuesday. “Despite its complicated relationship with the Court, the US has always stood strong against impunity, and supported the ICC’s jurisdictional mandate involving atrocities committed in Sudan and Libya.”

In his view, he added, “the Trump administration seeks to dismantle completely a legal entity, the sole purpose of which is to bring justice to victims of the most unimaginable atrocities.”

When asked, Bolton said he strongly supports US participation in multinational security organizations like NATO, which bring together sovereign nations in the pursuit of common defense interests. And while he espoused no enthusiasm for the UN, which he said is good mostly for “wasting” US taxpayers’ money, he added that most UN activities pose no threat to American sovereignty.

But Smeltz of the Chicago Council suggests that even such a neutral position on US multilateral engagement is out of touch with an American public that exhibits enthusiasm for global engagement – even at the price of some measure of national sovereignty.

“What we see is that Americans understand that to work with international institutions and within the multilateral system, we sometimes have to accept deals and rules that aren’t always going to be the United States’ first choice,” she says. “They get that some aspects of multilateralism might constrain us, but they support strong US involvement, and by wide margins, anyway.”