In push for police reform, small steps no longer enough

Loading...

| Dallas

When it comes to policing and violence, Ronal Serpas has what might seem like an odd suggestion: Wind the clock back 50 years.

As heated as the public debate around policing is today, years of social unrest had the United States in a similar place in the 1960s. In response, President Lyndon Johnson set up a commission to explore the problems and propose solutions.

His Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice, however, looked far beyond policing. It not only resulted in the 911 system and the first-ever crime victimization survey, but it also examined police, prosecution, defense, the courts, and corrections.

Why We Wrote This

Police reform used to be about small steps. But the past year has brought a seismic shift. The goal is now to reconsider the nature of policing itself.

Looking at today, “I hoped this would be a bellwether time, when we sat down and had a long think about what we should do as a country,” says Mr. Serpas, a former police chief in New Orleans and Nashville who now teaches criminology at Loyola University New Orleans.

But “we haven’t done that since Johnson,” he adds. “That’s the kind of change we need to think about. Global, large-scale change.”

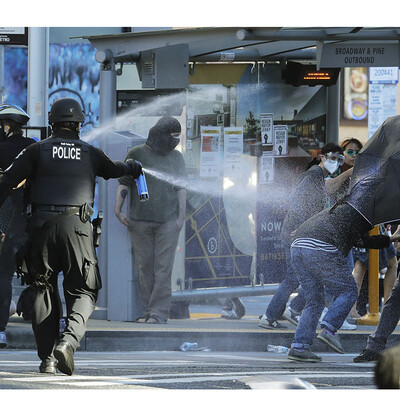

Not long ago, the push for police reform focused largely on incremental change such as pushing for body-worn cameras and improved training in de-escalation and implicit bias. But the year since George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer has changed that. Even with last summer’s push to “defund the police” faltering, reformers have raised their sights.

Amid some signs of progress, activists are less willing to settle, feeling that the way forward is no longer in small steps, but in fundamentally readjusting the balance between police and the communities they serve.

“Police don’t take back communities. Communities take back communities,” says Dominique Alexander of the Next Generation Action Network in Dallas. “That’s not anti-police.”

Signs of progress

Mr. Alexander says his views around how policing should be reformed have evolved over the years – but never more so than in this past year. Like many activists, he says his goal is not to “defund” the police but to “fund communities.”

He references a Donald Trump campaign ad from last year depicting a 911 call going to voicemail “due to defunding of the police department.”

“Nobody clapped back on that,” he says. “That type of fearmongering tactic is what has historically been used in this country.”

He’s encouraged by developments during the past year, including Dallas creating a civilian office overseeing police and an Office of Integrated Public Safety Solutions, even if they have flaws. And he says the post-George Floyd activism has played a crucial role.

“Those are awesome things, things that are monumental, things that we couldn’t do before,” he says.

Indeed, by some measures, policing has improved in recent years.

Police contacts with the public decreased from 2011 to 2015, with police contacts with Black people nearing the number with white people, according to (CCJ). Similarly, the disparity between Black and white arrest rates has narrowed over recent decades, particularly for drug offenses, CCJ found.

“That suggests that something has changed in policing. That’s police behavior,” says Nancy La Vigne, executive director of the CCJ Task Force on Policing.

“There has been progress,” she adds. “It’s just not fast enough for many of us.”

18,000

A major challenge for reform is the localized nature of the profession. There are more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S., and about 13,000 of those agencies have fewer than 25 full-time sworn officers, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. When states or cities adopt new policies or reforms – as they have been at a significant rate in recent years – it still falls on the individual agencies to implement and enforce those changes.

The Minneapolis Police Department, for example, adopted a “duty to intervene” policy in 2016 requiring officers to step in when they think a fellow officer is using unjustified force. Yet last summer, three officers stood by as Derek Chauvin knelt on the neck of a restrained Mr. Floyd for over nine minutes.

“You can’t pass all those reforms and not address some of the underlying issues that prevent those reforms having their intended impact,” says Dr. La Vigne.

“Each agency has its own culture that needs to be transformed,” she adds. “It’s a huge challenge.”

In the meantime, U.S. police have killed an average of 1,000 people a year since 2015, according to The Washington Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning . That number is far greater than in other developed countries. For example, in 2019, U.S. police killed 1,099 people. By comparison, Canadian police killed 21 people that year. In England and Wales, three people died in incidents with police.

Laurie Robinson hoped to be part of a U.S. transformation when she helped lead President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing in early 2015. It was six months of work crammed into two months, she says, and final recommendations centered around things like use-of-force policies, de-escalation training, and crisis intervention.

“It was very focused on what changes could be made within police departments by police departments,” says Professor Robinson, a criminologist at George Mason University.

The report didn’t give much attention to accountability measures that can play a big role in changing the culture and behavior of an agency. For example, qualified immunity shields most police officers from personal liability when they use excessive force.

But now there’s “tremendous attention in that area,” says Professor Robinson. She also points to “interesting experimentation” around the country on the subject of having someone besides police respond to low-level calls involving issues like mental illness and substance abuse.

“We have to sort out what needs to be done and who needs to do it. And then hold people accountable for doing it well,” she adds.

“Punishment to care”

Sara Mokuria, a co-founder of Mothers Against Police Brutality, has been doing some sorting of her own.

Over the years, she says, “my understanding of justice, and my understanding of healing, and my understanding of what solutions are have shifted and changed.”

For a long time, “I thought [only] about how to make [police] less harmful,” she says. But now “there is a possibility to make them obsolete.”

Ms. Mokuria became an activist on a Wednesday night in 1992, after police killed her father in front of her.

Amid a mental health crisis, he had been threatening her mother, Vicki, with a kitchen knife. She called the police, but she was able to get the knife off him and was about to take him on a walk around the neighborhood when the police arrived. He picked up the knife again, and moments later two Dallas police officers had shot him dead.

“He didn’t have to die,” The Dallas Morning News the next day. “It doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Ms. Mokuria’s immediate thought, as a 9-year-old, was to become a lawyer and put the cops in jail. She wanted to use the system that had killed her father to punish the officers.

In 2013, she helped found Mothers Against Police Brutality, a group that advocates for the families of victims of police violence. And after watching a series of police officers in the Dallas area get prosecuted, and convicted, for killing civilians in recent years, she’s only become more convinced that other solutions, broader changes, are needed.

Whether an officer is convicted or not convicted, and how long a sentence they get, “your loved one is still dead, and the system that killed them is still in place,” she says.

“Healing isn’t attached” to that, she adds. “We want to move from punishment to care.”

Re-imagining the role of police

Such large-scale change is what activists in Dallas, and around the country, are now calling for. They want more oversight of, and accountability for, police from the public and the courts. They want the root causes of crime addressed with social services, not handcuffs. They want America’s use of police to change fundamentally.

But reform advocates are calling for these sweeping changes at a fraught time. Violent crime has been spiking in cities around the country, and policing has never been as politicized as it is now. The us-versus-them narrative being used around police and reform activists, says Mr. Alexander, “is leading towards a major despair.”

Policing has improved in some respects thanks to reforms that Ms. Mokuria and others have pushed for, but it hasn’t been enough, she says. Reforms like those outlined by the 21st Century Policing task force may never be enough. But the fact that more people are coming to that realization feels like progress to some.

“A different understanding of what the role of police are, and the ability for those reforms to change the dynamics, is more widespread,” Ms. Mokuria says. “I didn’t believe that some of what’s happening now could be possible.”