In the summer of 1993, a Mississippi river town was submerged when two massive floods in a single month broke over the levees that were built after several other destructive floods. With 90% of their buildings damaged, the residents of Valmeyer made a bold decision: The entire town got up and moved to higher ground. Now, three decades later, Valmeyer is the poster child for a growing number of communities that are considering “managed retreat” – planned rather than forced relocation – from increasingly menacing seas and rivers as well as extreme storms.

“The first priority ought to be to move the people out of the way,” Valmeyer adviser Bill Becker told The Progressive magazine. “We could build expensive dams, levees, and seawalls to protect vulnerable communities, built to standards that may well fail the next time a storm breaks a record,” or, he added, we could heed the wisdom of “giving the floodplain back to the river.”

Indeed, government buyouts of flood-prone properties, long considered a radical response, are now proving to be more cost-effective than levees and repetitive building.

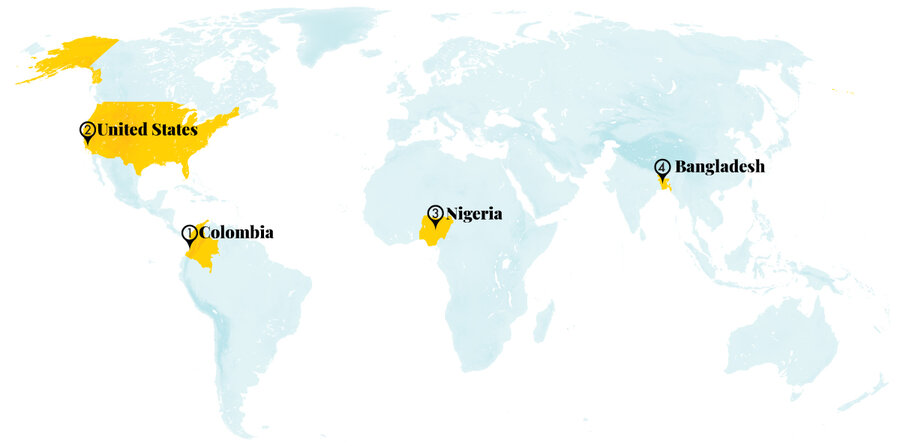

Of all climate disasters, floods present the highest costs and existential risks worldwide, affecting “nearly a third of the world population, more than any other peril,” according to a statement by Martin Bertogg, head of catastrophe perils at Swiss Re, the global reinsurance company.

The Columbia Climate School in New York says that by the end of this century 13 million Americans could be displaced by sea level rise. But with foresight and planning, many communities could avoid forced displacement through adaptation using nature-based infrastructure. For example, in the center of Bangkok – a city built on wetlands and subject to heavy rains – landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom has designed a park whose primary function is to gather, store, filter, and slowly release floodwaters in ways that serve people. Sloping buildings, roof gardens, wetlands, and vast underground reservoirs are joined by pervious walkways through a lush landscape leading to a museum, cafes, and other functional spaces.

In an interview with The New York Times, Ms. Voraakhom explained, “Right now, when we build for floods in Thailand, we see it with fear. We’re building dams higher and higher. That’s how you often deal with uncertainty – with fear. You need to deal with uncertainty with flexibility, with understanding. It’s OK to flood, and it’s OK to be ‘weak.’ That means resilience. With that mind-set, you create designs that talk with nature.”

“Higher ground” has come to mean more than climbing up the literal hill behind us. It means cultivating the new ground of a changed perspective and the creativity that comes with that new perspective: It’s moving out on the water as the Dutch are now pioneering in their floating communities; it’s directing water into “sponge parks” as Manchester, England, is planning; it’s nature-based infrastructures that clean our water, revive biodiversity, and reacquaint us with nature’s beauty.

Despite floods being the costliest and most common disaster in the United States, few states have developed adequate flood plans based on future rather than historical data. And yet, given the recently enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that includes $50 billion for climate resiliency programs along with other federal funding programs, states now have a unique opportunity to develop plans that will translate into real action.

Well-recognized expert on climate change adaptation, Dr. A.R. Siders of the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware, sums up the challenges before us: “It is such an opportunity to redesign the way we live with nature and with floods, and completely change how we deal with risk.” That kind of risk response earns the badge of resilience.

Clayton Collins

Clayton Collins