Russia’s first homefront casualties: Reporters and the press

Loading...

| Moscow

Russian troops have been violently waging their government’s so-called special military operation for over three weeks now in Ukraine. But on the homefront, state police and state prosecutors are waging a more intangible conflict.

The domestic casualties, so far, are mainly the thousands of Kremlin-critical voices, especially in the media.

Editor’s note: This article was edited in order to conform with Russian legislation criminalizing references to Russia’s current action in Ukraine as anything other than a “special military operation.”

Why We Wrote This

Russian media are imploding, with most independent outlets shut by the government and state-run outfits hit by mass resignations as reporters face up to the reality of their jobs.

Faced with public shock over the devastation caused by the military operation – which cannot be concealed from Russia’s huge internet-savvy population – Russian authorities have shuttered liberal news organizations. Ekho Moskvy radio station and TV Dozhd, , have already fallen victim to the crackdown.

Russian mainstream media have also seen many longtime employees depart, . Meanwhile, the English-language RT network has been virtually gutted by the sudden outflow of its foreign employees.

Many of those stepping out of their jobs are still not openly protesting against the conflict, but say they are Others are being forced to quit due to Western sanctions and bans on Russian media, like and , which is sometimes described as “Russia’s Google.”

The lure of state media jobs

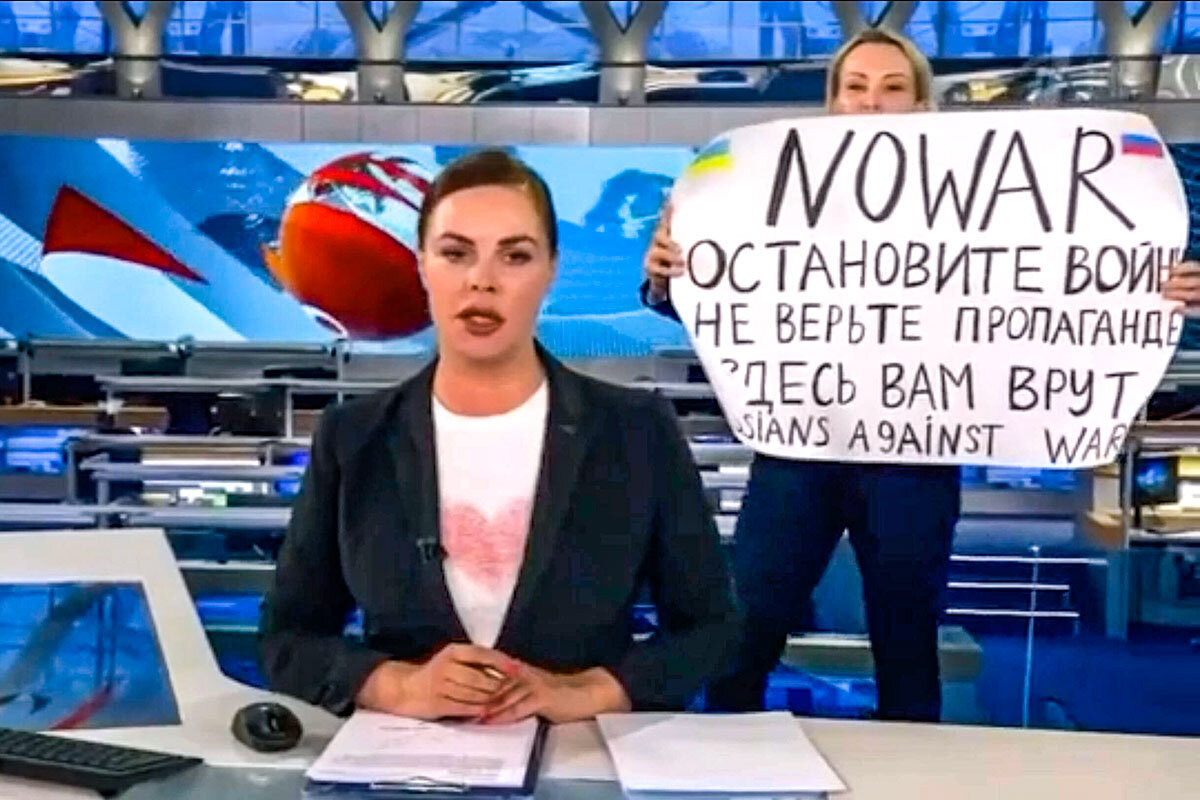

Attention has been riveted on the example of Marina Ovsyannikova, a longtime producer at Russia’s flagship Channel One state TV station who burst onto the evening news set with a dramatic anti-war poster, in a protest that has since been seen around the world. In she explained herself in terms that sound typical of youngish, middle-class professional Russians.

She is the child of a mixed Russian-Ukrainian marriage – as are large numbers of Russians – and had worked uncomplainingly in the bowels of state TV for years, taking her paycheck and averting her gaze. But she said that recent events forced her to confront the ugly truth. She blamed one person, Vladimir Putin, for what she described as a crime that has subjected all Russians to profound shame. She was arrested, but subsequently let go with a fairly minor fine.

Alexey Kovalyov, an editor with the Latvia-based , says he could easily have been in Ms. Ovsyannikova’s shoes.

He worked in a comfortable job with the state-owned RIA Novosti news agency until he was forced out in an internal takeover by hard-liners in 2013. Compelled to find another job, Mr. Kovalyov eventually found his place with Meduza, which has produced some of Russia’s best alternative journalism and been declared a “foreign agent” by authorities.

A few days ago, Mr. Kovalyov and his wife quietly slipped across the border into Latvia, where he has resumed his work with Meduza, whose website is now blocked in Russia.

“If I hadn’t lost my job in 2013, I could still be sitting there” like Ms. Ovsyannikova, he says. “After all, I wasn’t making propaganda. I was mostly translating articles from the foreign press into Russian. Like so many others, I could tell myself that I wasn’t doing anything wrong, just performing my job.”

Still in touch with old friends from Russia’s media world, Mr. Kovalyov says many are in shock at what has happened. “People are telling me that they are devastated, feel blindsided. They’ve continued for eight years,” since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, “doing ‘nothing wrong.’ People now feel shame over their complicity. And yeah, that could have been me.

“This is the nature” of the Putin model, he says. “It’s a set of compromises where good people work in bad institutions, for a bad regime. They accepted the deal, in which the Kremlin took care of politics and they enjoyed the rewards and didn’t get involved. We can now see this order crashing before our very eyes,” he says.

Mr. Kovalyov says that Meduza is still going strong and retain most of their Russian readers who use virtual private networks (VPNs) on their computers, something Meduza has .

“It can end at any moment”

For many years Alexey Venediktov steered Ekho Moskvy, the scrappy Moscow radio station that was owned by the media wing of the state natural gas monopoly Gazprom, but which provided a regular perch for some of the Kremlin’s harshest critics. That’s all over now. The station has been closed down, and Mr. Venediktov says he is unemployed.

“When the military operation was declared, propaganda had to be total,” he says. “It’s odd, if there is no war, why do we have military censorship?”

Ekho Moskvy’s staff has scattered, he says. “Modern technology enables some to continue with their own information channels. But, if tomorrow YouTube or Telegram cease to exist, there will be nothing left. For former journalists, it’s now a struggle for survival. People have families to support, rent to pay.”

The single opposition news outlet still standing is Novaya Gazeta, a newspaper co-founded by Mikhail Gorbachev. Its editor, Dmitry Muratov, won the Nobel Peace Prize last year, together with a Filipina journalist, for “their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

The paper survives by striking a difficult compromise, says Nadezhda Prusenkova, Novaya Gazeta’s press secretary.

“We pulled any materials that did not meet the demands of the new law on fake news,” she says. “We have to work under conditions of military censorship, and limit ourselves. Not only can we not call [it] a war, but we may not report about what’s happening in Ukraine or anything our armed forces are doing. Otherwise, there is criminal punishment of 15 years in prison.

“We thought about closing down, had a stormy staff meeting, but decided we had a responsibility to continue. There is a lot we can do under the existing conditions, a lot of valuable stories to report, and as long as we can go on, we will. We realize it can end at any moment,” she adds.

Some observers see the censorship as auguring a profound social crisis. Things can’t go on like this for very long, says Boris Kagarlitsky, a veteran left-wing Kremlin critic, who holds the distinction of having served jail time for his dissenting views under three different Soviet and Russian regimes.

“Russia’s elite knows that there is a storm coming, the Putin order is falling apart, and this is all going to end very badly,” he forecasts. “Our generation already experienced revolutions and political dramas galore. So, it looks like we’re headed for another one.”