Worse than the Cold War? US-Russia relations hit new low.

Loading...

| Moscow

Russia’s relations with the West, and the United States in particular, appear to be plumbing depths of acrimony and mutual misunderstanding unseen even during the original Cold War.

After years of deteriorating relations, sanctions, tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions, and an escalating “information war,” some in Moscow are asking if there even is any point in seeking renewed dialogue with the U.S., if only out of concern that more talking might just make things worse.

Events have cascaded over the past month. Russia’s treatment of imprisoned dissident Alexei Navalny, who has been sent to a prison hospital amid reports of failing health, underlines the sharp perceived differences between Russia and the West over matters of human rights. Meanwhile, a Russian military buildup near Ukraine has illustrated that the conflict in the Donbass region might explode at any time, possibly even dragging Russia and NATO into direct confrontation.

Why We Wrote This

With its relations with Washington at a nadir, Russia is eyeing a more pragmatic, if adversarial, relationship with the U.S. in the hopes of getting the respect it desires.

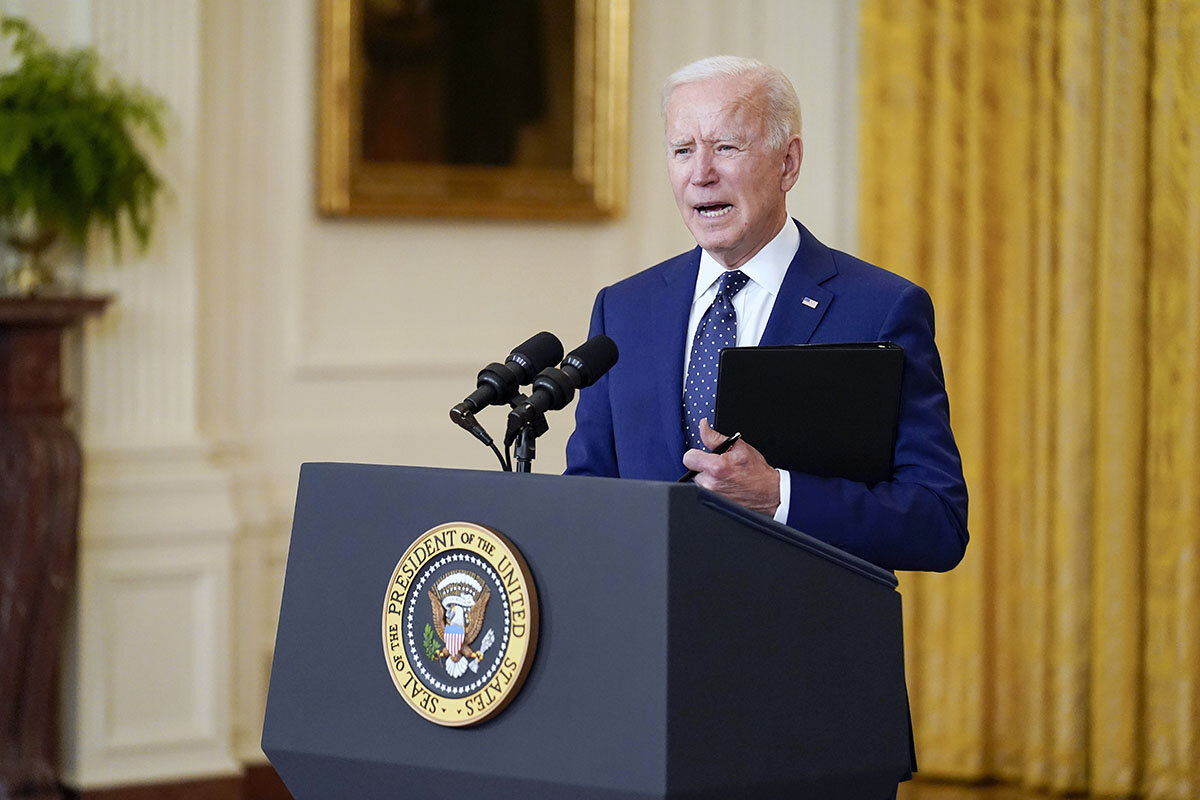

President Joe Biden surprised the Kremlin by proposing a “personal summit” to discuss the growing list of U.S.-Russia disagreements in last week. He later spoke of the need for “disengagement” in the escalating tensions around Ukraine, and postponed a planned visit of two U.S. warships to Russia-adjacent waters in the Black Sea.

But days later he also imposed a package of tough sanctions against Russia, for its alleged SolarWinds hacking and interference in the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, infuriating Moscow and drawing threats of retaliation. Last month, after Mr. Biden agreed with a journalist’s intimation that Mr. Putin is a “killer,” the Kremlin ordered Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. to return home for intensive consultations, an almost unprecedented peacetime move. Over the weekend, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov suggested that the acting U.S. ambassador to Moscow, John Sullivan, should likewise go back to Washington for a spell. On Tuesday, Mr. Sullivan do just that this week.

And there is a growing sense in Moscow that the downward spiral of East-West ties has reached a point of no return, and that Russia should consider abandoning hopes of reconciliation with the West and seek permanent alternatives: perhaps in an intensified compact with China, and targeted relationships with countries of Europe and other regions that are willing to do business with Moscow.

“Things are at rock bottom. This may not be structurally a cold war in the way the old one was, but mentally, in terms of atmosphere, it’s even worse,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “The fact that Biden offered a summit meeting would have sounded a hopeful note anytime in the past. Now, nobody can be sure of that. A hypothetical Putin-Biden meeting might not prove to be a path to better relations, but just the opposite. It could just become a shouting match that would bring a hardening of differences, and make relations look like even more of a dead end.”

Room for discussion

Foreign policy experts agree that there is a long list of practical issues that could benefit from purposeful high-level discussion. With the U.S. preparing to finally exit Afghanistan, some coordination with regional countries, including Russia and its Central Asian allies, might make the transition easier for everyone. One of Mr. Biden’s first acts in office was to extend the New START arms control agreement, which the Trump administration had been threatening to abandon, but the former paradigm of strategic stability remains in tatters and requires urgent attention, experts say.

“If you are looking for opportunities to make the world a safer place through reason and compromise, there are quite a few,” says Andrey Kortunov, director of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “There are also some areas where the best we could do is agree to disagree, such as Ukraine and human rights issues.”

The plight of Mr. Navalny, which has evoked so much outrage in the West, seems unlikely to provide leverage in dealing with the Kremlin because – as Western moral authority fades – Russian public opinion appears indifferent, or even in agreement with its government’s actions. Recent surveys in Moscow, Russia’s only independent pollster, found that fewer than a fifth of Russians approve of Mr. Navalny’s activities, while well over half disapprove. An April poll found that while 29% of Russians consider Mr. Navalny’s imprisonment unfair, 48% think it is fair.

Tensions around the Russian-backed rebel republics in eastern Ukraine have been much severer than usual, with a spike in violent incidents on the front line, a demonstrative Russian military buildup near the borders, and strong U.S. and NATO affirmations of support for Kyiv. The Russian narrative claims that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy triggered the crisis a month ago by that makes retaking the Russian-annexed territory of Crimea official Ukrainian state policy. Mr. Zelenskiy has also appealed to the U.S. and Europe to expedite Ukraine’s membership in NATO, which Russia has long described as a “red line” that would lead to war.

But Russian leaders, who have been at pains to deny any direct involvement in Ukraine’s war for the past seven years, now say openly that they will fight to defend the two rebel republics. Top Kremlin official Dmitry Kozak even , it could be “the beginning of the end” for Ukraine.

“This is a very desperate situation,” says Vadim Karasyov, director of the independent Institute of Global Strategies in Kyiv. “We know the West is not going to help Ukraine militarily if it comes to war. So we need to find some kind of workable compromises, not more pretexts for war.”

Time to turn eastward?

In this increasingly vexed atmosphere, the Russians appear to be saying there is no point in Mr. Putin and Mr. Biden meeting unless an agenda has been prepared well in advance, setting out a few achievable goals and leaving aside areas where there can be no agreement.

“Russia isn’t going to take part in another circus like we had with Trump in Helsinki in 2018,” says Sergei Markedonov, an expert with MGIMO University in Moscow. “What is needed is a deeper dialogue. That could begin if we had a real old-fashioned summit between Biden and Putin, one that has been calculated to yield at least some positive results. We need to find a modus vivendi going forward, and the present course is not leading there.”

Alternatively, Russia may turn away from any hopes of even pragmatic rapprochement with the West, experts warn.

Mr. Lukyanov, who maintains close contact with his Chinese counterparts, says they felt blindsided at a summit with U.S. foreign policy chiefs in Alaska last month, when what they expected to be a practical discussion of how to overcome the acrimonious Trump-era legacy in their relations turned into what they saw as a U.S. lecture about how China needs to obey the “rules-based” international order.

“It was the Chinese, in the past, who were very cautious about participating” in anything that looked like an anti-Western alliance, says Mr. Lukyanov. “We are hearing a new tone from them now. Now our growing relationship with China isn’t just about compensating for a lack of relations with the U.S. It’s about the need to build up a group of countries that will resist the U.S., aimed at containing U.S. activities and policies that are harmful to our two countries.”