Other nations had a pandemic reckoning. Why hasn’t the US?

Loading...

On May 12, 2020, an American astronaut beamed a vital message down to Earth. His home country, and half the world’s population, was in lockdown – an unprecedented response to a pandemic.

Commander Chris Cassidy had a vantage point that was literally above it all. A 250-mile-high view, in fact.

During a live TV from the International Space Station, he described Earth as “a big, beautiful spaceship that has 7 billion astronauts on it.” Floating like a marionette in the low gravity, Mr. Cassidy described working in harmony with his crew of two Russian cosmonauts. Their safety and effectiveness depended on it.

Why We Wrote This

The pandemic exacerbated growing distrust between elites and citizens. That has made it hard to take stock of why the United States fared worse than many other countries. Those calling for a pandemic reckoning say it could help rebuild trust.

“That’s what we should be doing on Earth,” said Mr. Cassidy, as he urged viewers to do their part to keep everyone healthy. “Together as a crew on planet Earth, we can make anything happen.”

Initially, his fellow Americans adopted that spirit. supported the lockdowns early on, according to a March 2020 Pew study. Millions of Americans stayed home from work; donned masks when they stepped outside, even for solo walks in the woods; kept their children home from school; attended church by Zoom; and stopped getting on airplanes.

But that support frayed as the pandemic became increasingly politicized in the United States – the most politicized, in fact, of 14 countries surveyed by the Pew Research Foundation in the summer of 2020. By the second anniversary of the pandemic, the percentage of Democrats following masking and social distance practices was greater than Republicans.

Part of the reason for the divide was that as citizens learned that declarations from public health officials and politicians had been incomplete or incorrect, some became skeptical or distrustful of scientists, journalists, and public officials.

“A lot of reckoning needs to be done,” says Michael Levitt, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist at Stanford University who has spent the past few years conducting data analysis of COVID-19 fatality rates.

Sweden formed a commission in 2020 to evaluate its approach to the pandemic, and submitted its two years later. A similar body in the United Kingdom turned in its in 2023. But the U.S. has yet to establish such a commission, let alone make a report. A congressional bill to set up a bipartisan inquiry, modeled on the 9/11 Commission, stalled out in both the House and Senate in 2022.

So any reckoning of how the U.S. government handled the pandemic has been piecemeal at best. Those interviewed for this article believe a reckoning of what went wrong – and why – is needed. They say it’s necessary not only for understanding how best to manage a pandemic, but also to rebuild the trust that was eroded.

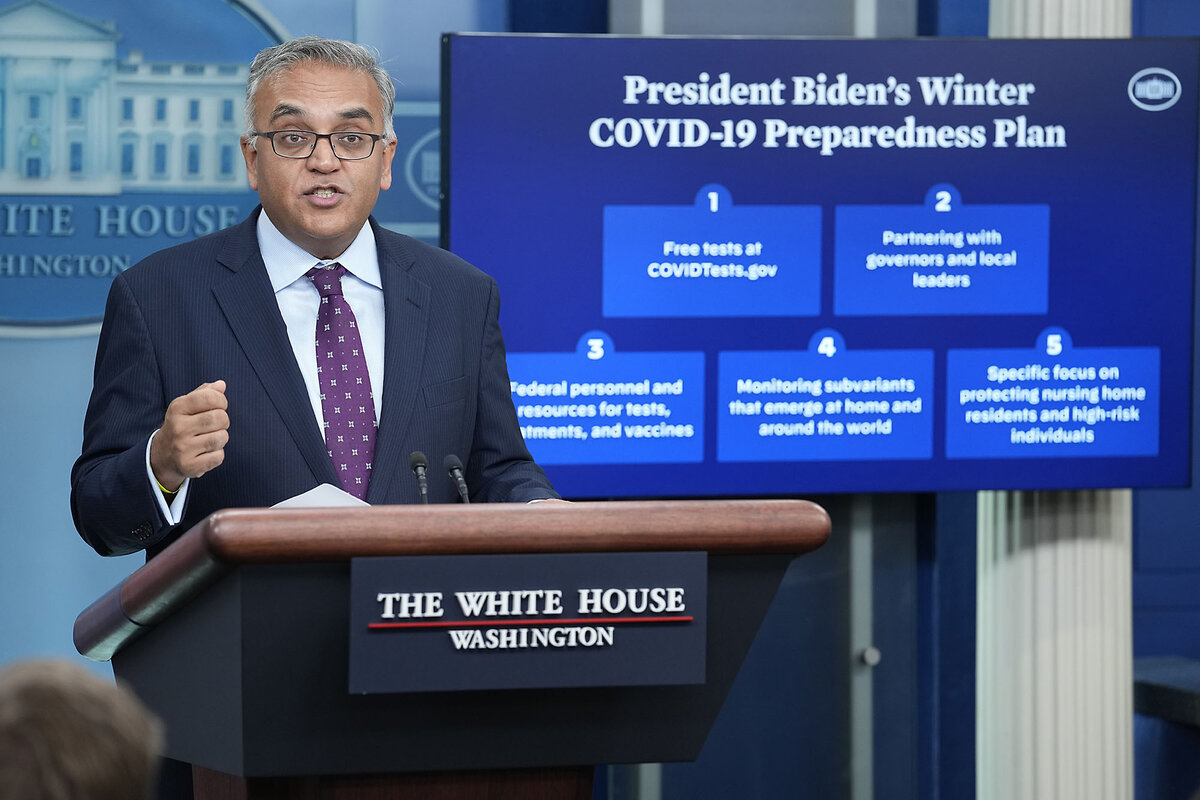

“You’re not going to restore trust in public health until you take some accountability for the mistakes you’ve made,” says Ashish Jha, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator under President Joe Biden. “Then you’ve got to just keep spreading good information and you’ve got to build allies to do that across the political aisle.”

The public was told in March 2020, when President Donald Trump recommended social distancing measures and the country effectively shut down, that Imperial College London had estimated that 2.2 million people would die in America alone by August if preventive measures were not taken. The American death toll reached 1 million in May 2022.

The public was told that it to wear masks – and then that it did, an about-face that senior White House adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci as due to the need early on to prioritize masks for health care workers. Then in January 2023, the Cochrane Library, an institution dedicated to evidence-based medicine and meta-analysis of medical studies, reviewed 78 trials of masking over several decades. It included two that assessed masking during COVID-19. The review concluded that it’s “uncertain” whether masks indeed slow the spread of viruses such as the one that causes COVID-19.

The public was told that it must keep 6 feet away from other humans, a guideline that hampered weddings, funerals, and the education of an entire generation of American students. Then in January 2024, Dr. Fauci that the 6-foot rule “wasn’t based on data.” Former Trump administration official Scott Gottlieb called it the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s .

At every step, these sweeping measures were justified by leaders the public to “follow the science.” The public was told it was for the , and those who urged a more rigorous cost-benefit analysis were . Critics, including those interviewed for this piece, say that public health officials did not adequately weigh the potential for economic costs, learning loss, mental health issues, and “deaths of despair” – including from suicide, drug overdoses, and drinking.

A by Brown University found that at the end of the pandemic in spring 2023, the U.S. accounted for 15% of officially reported COVID-19 deaths worldwide. That’s triple its share of the global population. The scale of fatalities was “unacceptable,” according to Dr. Fauci, who served as a top adviser to both the Trump and Biden administrations and came to personify the public health establishment’s pandemic response.

“On a per-capita basis we’ve done worse than virtually all other countries,” he told The New York Times Magazine in a about the pandemic, in which he lamented national divisiveness and suspicion and also pointed to areas in which public health officials could have done better. “There’s no reason that a rich country like ours has to have 1.1 million deaths.”

What the U.S. got wrong – and the consequences

Early in 2020, public health officials talked about waging war on the virus in a bid to end the pandemic through concerted, coordinated efforts. Stephen Macedo, a politics professor at Princeton University, sums up their message: “The only way we can win is if everyone gets in line and supports the generals.”

So as the federal government (first under President Trump, and then President Biden) urged sweeping measures to contain the virus, many state and local officials, universities, and scientific publications joined in that messaging.

“It wasn’t sober. It wasn’t data-based. It was fearmongering,” says Dr. Monica Gandhi, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who often found herself frustrated with public health officials’ resistance to reconsidering policies based on new information.

As media outlets reflected the growing polarization, they were criticized on one side for entertaining dissenting viewpoints and misinformation, while others accused them of a lack of rigor. Meanwhile, scientists with relevant expertise who were raising questions about the data, modeling, and policy recommendations often got sidelined.

One example is masking policy.

Early on, Dr. Gandhi in frequent TV and newspaper appearances. More than a year later, a large-scale randomized trial of masking changed her mind, though she still recommended that individuals at high risk wear masks. Yet now that her expert assessment was going against the grain of public health messaging, it was no longer valued. “I got really attacked for turning against masks,” says the doctor and professor.

Dr. Jha wasn’t yet a member of the Biden administration when vaccines were rolled out, but he says there were mistakes in the communication about them. The COVID-19 vaccines have a safety profile that is good, he says, but using the shorthand description of COVID-19 vaccines as “safe” wasn’t adequate. The risks of side effects, even if low, weren’t conveyed.

As for the effectiveness of the vaccines? Dr. Jha says that the vaccines saved many lives by reducing the severity of the disease and preventing hospitalization. in late 2022 estimated the vaccines had prevented more than 3 million deaths in the U.S. Yet vaccinated individuals still became infected and spread the disease to others, which critics said a key justification for vaccine mandates.

By July 2021, a significant COVID-19 outbreak occurred in Provincetown, Massachusetts, among fully vaccinated individuals. What were initially dubbed “breakthrough cases” became common across the U.S. A published in November 2022 found that when the delta variant hit highly vaccinated Israel, “Two-dose vaccine efficacy against infection dropped significantly from >90% to ~40% over 6 months.”

“The virus continued to evolve,” says Dr. Jha, who is now dean of Brown University’s Public School of Heath. “That made it very difficult for the vaccines to keep up. All of that should have been communicated more effectively.”

He rues that federal vaccine mandates, a policy he initially supported but now views as a mistake, were in place for far too long – until May 2023.

“The long-term negative effect was that I think it did undermine confidence in vaccines for a lot of people,” says Dr. Jha.

This year, a found that 26% of Republican respondents are bypassing or putting off recommended childhood vaccinations. That’s a 13-point rise since 2023.

Dr. Gandhi was also an early supporter of vaccine mandates. But by 2022, she was publicly arguing that they were too socially divisive. The population-wide policy didn’t make sense, given that the purpose of the vaccines was to prevent serious illness, she wrote in “Endemic: A Post-pandemic Playbook.” She says that officials were slow to update other messaging and policies as well.

that COVID-19 doesn’t transmit as easily outdoors. Yet local governments padlocked playgrounds, boarded over basketball hoops, and filled in skate parks with sand. People were fined for . They were apprehended for . Houses of worship were ordered shut. Violators were sometimes arrested. Human rights organizations warned of the long-term impacts on civil liberties.

There were extraordinary economic costs, too. According to a study published in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, the supply-and-demand shocks “represent a reduction of around one-fifth of the US economy’s value added, one-quarter of current employment, and about 16 per cent of the US total wage income.” In response, the Trump administration passed the CARES Act and sent out the first of to everyone. It triggered the that took off under the Biden administration, which dispatched another round of checks as part of a $1.9 trillion bill in March 2021.

For many parents across the U.S., the most damaging aspect of lockdowns was school closures. revealed that kids were at more risk from drownings or car accidents than from COVID-19. During the first half-year of the pandemic, people under age 15 accounted for a mere 0.04% of fatalities. Many European countries reopened schools safely and without COVID-19 outbreaks in the fall of 2020. However, according to a July 2020 Franklin Templeton-Gallup , people in the U.S. believed children were 40 times more likely to die than the actual rate, and in many areas they supported keeping schools closed for up to 18 months.

“This is a perfect example of the failure of our health officials and the media – that people just had no clue about the risk level of the children,” says David Zweig, author of “An Abundance of Caution: American Schools, the Virus, and a Story of Bad Decisions.”

During the pandemic, there was a . Even when all the schools had fully reopened, many children still didn’t return. In the 2022-2023 school year, chronic absenteeism in the U.S. was at .

Despite its stringent measures, the U.S. fared than other wealthy nations. between 2020 and 2023. The excess death rate in the U.S. included a in “deaths of despair,” such as those from . Alcohol deaths alone by 29% for women and 27% for men in the U.S. Poor and marginalized people were especially hard-hit, says John Ioannidis, a highly cited Stanford professor of medicine, epidemiology, public health, and biomedical data.

Dr. Ioannidis would like America to start thinking big to address those disparities because they go beyond just the impact of the coronavirus.

“We need a new contract,” he says, noting the decline in life expectancy during the pandemic despite hefty spending on health. “We’ve lost touch with other highly developed nations in that regard.”

The authority that officials claimed during the pandemic, during which issued emergency orders, also has some citizens questioning the contract between the people and the government elected to serve them.

“It was as though somehow we had ceded the total authority over our lives to a group of people who saw absolutely no value in the things that make life worth living, you know, in human connection,” says Kat Rosenfield, a novelist and culture writer for The Free Press who has also written for The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and UnHerd.

In the year before the pandemic, Ms. Rosenfield enjoyed visiting her 104-year-old grandmother and hearing her recount how her Finnish immigrant family arrived in the U.S. via Ellis Island, or how she’d applied to be a coat girl at New York City’s Roseland Ballroom but was turned down because she wasn’t pretty enough.

“She was still as [mad] about this as if it had happened last week,” recalls Ms. Rosenfield. “It was so much fun to hear stories like that from her.”

Then came lockdowns. New Jersey prohibited Ms. Rosenfield from visiting her grandmother.

“She, I think, just really went downhill very, very fast,” says Ms. Rosenfield. “Once she couldn’t receive visitors anymore, it was very, very quick.”

Helen Kelly died without anyone at her bedside to hold her hand.

Just weeks after her family was informed that they couldn’t hold a funeral because that would require gathering – even if they did it outside – Ms. Rosenfield watched as masses of people protested the killing of George Floyd shoulder to shoulder.

In a U-turn that left skid marks on the credibility of public health messaging, experts had a new message. As , “Suddenly, Public Health Officials Say Social Justice Matters More Than Social Distance.”

They didn’t just allow such gatherings to happen, says Ms. Rosenfield. “They suggested it was a moral imperative.”

Why mistakes were made in the name of “follow the science”

In response to a panicked populace, top officials had sprung into action. Federal policymakers focused on an overriding goal: Stop infections and save lives.

“People are in public health because they believe that they can help people. It’s a noble goal,” says Mr. Zweig. “Their profession is based on a belief that we can intervene to help people and society. So this is an ideology. It’s a belief system.”

The downside, he says, is that officials may be reluctant to admit they don’t know what the best course of action is. For those overseeing a public health response, it’s difficult to be in favor of taking limited action – or none at all. Those who did dial things back were often excoriated. For example, when Georgia loosened lockdown restrictions in April 2020, The Atlantic decried, “Georgia’s Experiment in Human Sacrifice.” An all-or-nothing approach, rather than a risk-benefit analysis, sometimes dominated policymaking.

“People in medicine and public health don’t have any particular expertise in the trade-off of values,” says Gregory Pence, a bioethicist at the University of Alabama and author of “What Went Wrong: America’s Covid Response and Lessons for the Future.”

Dr. Fauci has acknowledged that – but also defended the importance of public health officials sharing their expertise.

“At least to my perception, the emphasis strictly on the science and public health – that is what public-health people should do,” he The New York Times Magazine, adding that it is for people in positions that aren’t exclusively about public health to make broader assessments. “Those people have to make the decisions about the balance between the potential negative consequences of something versus the benefits of something.”

While scientists often recognized the need for policymakers to weigh trade-offs, some elites used “follow the science” as a rhetorical cudgel to urge certain behaviors, including compliance with lockdowns, as well as mask and vaccine mandates. Some attacked individuals who publicly disagreed with stay-at-home orders as “selfish.”

The co-authors of a recent book, “In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us,” developed a term for that: moralized antagonism. Mr. Macedo and Frances Lee observe that a partisan divide emerged as red states began to reopen and blue states stayed closed.

“I think they saw people who had reopened as bad people, and that there’s nothing to be learned from bad people,” says Ms. Lee, referring to liberal elites. Her book chronicles a correlation between political partisanship and how long schools stayed closed.

In spring 2020, the American Association of Pediatrics to reopen schools, warning about the negative impacts of remote learning. However, after President Trump pressed for the reopening of schools that July, its messaging toward advocating for schools to remain closed. It issued a fresh statement, cosigned by two national teachers unions, that now emphasized maximizing safety for children and teachers as a requirement for reopening schools. “Public health agencies must make recommendations based on evidence, not politics,” the AAP wrote. Other organizations, including media outlets, quickly shifted, too.

“It was a very reactionary response to Trump,” says Dr. Gandhi, who describes her politics as “left of the left.” “So, if he said one thing, like, ‘It’s 12 o’clock,’ the public health establishment would say, ‘No, it is 2 o’clock.’”

To be sure, Mr. Trump said a number of things that went against prominent scientists’ assessments. The president that the virus would miraculously disappear. During a press conference, he recommended that scientists try injecting people with household disinfectant as a possible COVID-19 cure. Controversially, he also recommended ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug prescribed for people and animals.

Ms. Lee says that Democrats’ lack of trust in President Trump, who was up for reelection, contributed to extending the closures.

“Donald Trump was like, ‘We need to open schools,’” says Dr. Jha. “So there were a bunch of people who were like, ‘I don’t like Donald Trump; therefore we should not open schools.’ And I was like, ‘What if I don’t like Donald Trump, but I want to open schools? Like, can we do that?’”

Entrenched positions

Another factor was confirmation bias, says social psychologist Carol Tavris. One example: her reaction to the Great Barrington Declaration.

In October 2020, Sunetra Gupta of the University of Oxford, Martin Kulldorff of Harvard University, and Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University warned that the blanket lockdown policies were damaging to the economy, education, and other aspects of mental and physical health. Meeting in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, they proposed a “focused protection” approach instead: “Allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk.”

Dr. Francis Collins, then-director of the National Institutes of Health, emailed Dr. Fauci, then-director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, to recommend “a quick and devastating published take down of its premises.”

In 2020, Facebook briefly took down the Great Barrington Declaration’s page on its site. (Amid broader criticism that social media did the bidding of the White House, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has since the Biden administration of pressuring social media companies to censor information about COVID-19.) YouTube removed a video of a panel discussion with the declaration’s founders that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis hosted, saying in a that it “contradicts the consensus of local and global health authorities.”

Ms. Tavris, for one, bought into the messaging that the founders of the Great Barrington Declaration were fringe scientists.

“I certainly remember feeling, ‘I don’t want to know this,’” says Ms. Tavris, co-author of “Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me),” because it conflicted with what the scientists she trusted had been saying.

“To reduce that uncomfortable feeling, we will overlook, forget, or trivialize any information that disconfirms our beliefs,” says Ms. Tavris, who now believes that the founders – and the tens of thousands of health workers who cosigned the declaration – had a legitimate case to be made that should not have been dismissed out of hand. “This is what causes us only to see and remember and hear arguments that support what we believe and dismiss those that do not.”

Ms. Tavris adds that the COVID-19 pandemic polarized so many people politically – Whom to trust? Whom to believe? – that once people took a position, it was very hard to accept evidence that they were wrong. Or that “the other side” may actually have had some good ideas.

For those who have vested interests in the programs and policies they’ve advocated for, there can be an added layer of resistance: Their reputations are at stake.

Moreover, educated elites can have a tendency toward groupthink, philosopher Sissela Bok warned in her 1978 book, “Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life.” Believing they are the “wise and virtuous ones,” they can be tempted to tell “noble lies” to compel public action, says Mr. Macedo, whose book utilizes Ms. Bok’s insights.

That can backfire.

“I think people were worried somehow that if we communicate uncertainty, people will have less faith in us,” says Dr. Jha. “I actually think it’s the opposite. I think when you communicate uncertainty, people have more faith in you because they see you as an honest broker.”

Mr. Pence, the bioethicist, agrees.

“There are people who think that absolute, universal statements are the best to get compliance. That has failed,” he says. “Not giving people the whole truth has made people more distrustful.”

This story is the first in a two-part series. Click here to read Part 2: “The pandemic divided the US. Could a full accounting help the nation heal?”