Why Bollywood is cranking out pro-government films ahead of India’s election

Loading...

| Delhi

A burqa-clad woman walks through a bleak version of Srinagar in India-administered Kashmir. She’s an undercover agent hot on the trail of a young separatist militant.

Over the next 2 1/2 hours of the recent Bollywood production, titled “Article 370,” the audience follows her action-packed journey against the backdrop of the troubled Himalayan region.

The movie’s climax? The Indian government’s real-life decision to revoke Kashmir’s special autonomy in 2019. That shocking move and a subsequent media blackout were broadly criticized by human rights organizations and the international media, but “Article 370” celebrates it unequivocally.

Why We Wrote This

An uptick in brazenly pro-government Bollywood movies highlights the close relationship between India’s ruling party and mainstream media – as well as the risks of blurring the lines between politics, news, and entertainment.

The movie ends with a montage of positive headlines about Kashmir, set to uplifting music, and a shot of Prime Minister Narendra Modi – played by actor Arun Govil – smiling as he reads a newspaper article extolling his decision.

“Article 370,” named after the constitutional article that formerly granted Kashmir some autonomy, is one of several films with striking pro-government narratives released just ahead of the country’s massive general election, which begins this month.

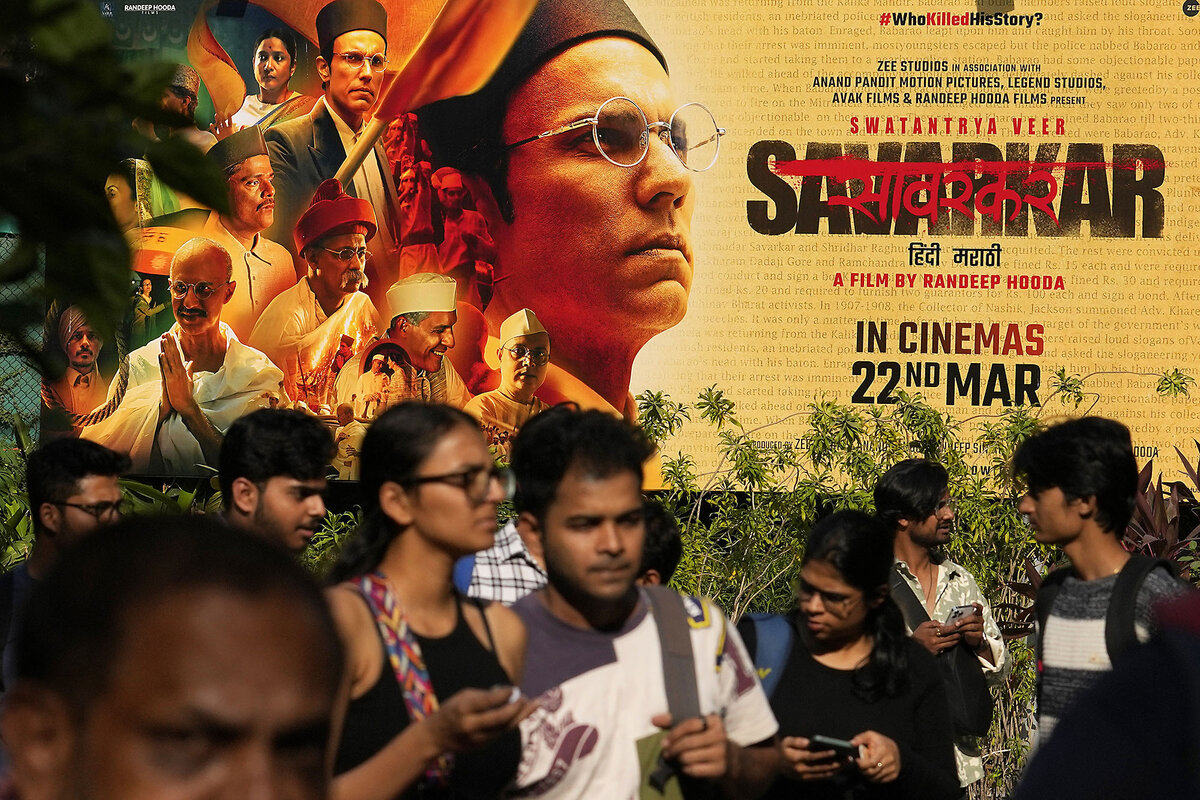

Another is a biopic of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a radical leader who opposed Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance and founded the Hindu nationalist ideology embraced by Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). And “JNU” – a film that appears to cast Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, long considered a leftist bastion, as working against the nation – is set to reach theaters later this month.

The new releases reflect a broader shift in Indian cinema over the past decade, one that some critics say has transformed Bollywood into an extension of the prime minister’s PR machine. Films that support the BJP’s stance are often given tax breaks at the box office and get shoutouts from government ministers. Films that don’t face swift and intense backlash.

“Mainstream Hindi cinema [or Bollywood] has always been pro-establishment,” says Sreya Mitra, associate professor of media studies at the American University of Sharjah. “But you’ve never witnessed so much explicit alignment with the establishment to the extent that it is parroting the same lines.”

Bollywood under Mr. Modi

Media experts say Bollywood movies have always reflected the collective anxieties of the nation. Villains in the past were mysterious foreign entities or rich industrialists profiteering by duping the masses. These days, the bad guy is often a liberal, an opposition figure, or a Muslim.

“The Kerala Story” (2023) depicts Muslim men luring Hindu women and recruiting them into the Islamic State, mirroring a widespread Hindu right-wing conspiracy theory called “love jihad.”

The latest films feature cameos of the prime minister’s character – flanked by the Indian tricolor and delivering punchy dialogues with a steely gaze – and “explicit rewriting of historical narratives,” says Dr. Mitra. “It is very much in alignment with the populist sort of deification of Modi himself,” she says.

What is shown on the screen can have real-world consequences. “The Kashmir Files” (2022) showed graphic and hyperbolic depictions of violence against Kashmiri Hindus by Kashmiri Muslims. After watching the film, some Hindus made rousing in movie halls.

Implicit censorship

When a film veers from these formulas, Hindu hard-liners have quickly mobilized in protest.

In 2017, right-wing Hindu nationalist groups against the actor of a period drama when rumors spread that it contained scenes depicting a romance between a Hindu queen and a Muslim ruler. And in 2021, makers of a political drama series streaming on Amazon for scenes that allegedly disrespected Hindu gods and the office of the prime minister, and made changes to their show.

In this environment, nuanced portrayals of religious and sociopolitical issues are rare, says Dr. Mitra.

The implicit censorship extends to the press, too. Kunal Majumder, India representative at the Committee to Protect Journalists, lists several disturbing trends over the past decade: an uptick in police complaints against reporters, the unprecedented use of anti-terror laws against journalists, and foreign journalists’ visas being revoked, among others.

Several news outlets, including Hindi-language newspaper Dainik Bhaskar and the BBC, have also faced tax raids after they published stories critical of the government.

“When something like this happens, it sends a chilling effect,” says Mr. Majumder.

The government is a major source of advertising revenue for big media companies, he adds, which makes news outlets wary of running stories that could upset those in power. Plus, many of India’s top news organizations are now controlled by billionaires close to Mr. Modi, including , Gautam Adani. In 2022 he acquired NDTV, one of the last remaining networks that pursued hard-hitting coverage.

“India’s vast media landscape has been captured by the BJP,” says Zoya Hasan, professor emerita at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Fawning coverage of the Modi administration’s policies or the echoing of sensationalist anti-Muslim narratives have earned a large section of Indian media the moniker godi or “lap dog” media.

To be sure, Mr. Modi and the BJP are extremely popular throughout the country. A Pew Research Center survey showed , who is expected to easily win a third term in the upcoming elections, which begin April 19. But observers say the pro-government bias in entertainment and news media can warp viewers’ perception of Indian politics and exacerbate fault lines in Indian society.

Propaganda or point of view?

“Article 370,” like many new releases, has been labeled “” by critics. Anjali Sharma, who caught a recent showing in the Delhi suburb of Gurugram, agrees such films can be one-sided. “What is shown to us and what is happening [in Kashmir], there is a lot of difference,” she says.

But Siddharth Bodke, who plays a leading role as a right-wing Hindu nationalist student leader in the upcoming “JNU,” says these films merely present audiences with a certain point of view. He insists that his film is “balanced,” adding that if he had the opportunity to do a more anti-establishment film – and the script was good – he would take it.

Either way, audiences are buying in.

At the Gurugram screening of “Article 370,” the theater was three-quarters full even a month after the movie’s release. “The Kerala Story” and “The Kashmir Files” also had successful runs at the box office, though .

Filmmakers today feel they can milk the country’s current sociopolitical climate, says Dr. Mitra, but if more movies flop, they will stop.

Could these movies shape voter opinions? Maybe over a long period, says moviegoer Dinesh Bansal. But not him, he adds. “I always look at the entertainment quotient,” he says. “I don’t think too much about the messaging.”