In Japan, too, voters want their country to be ‘great again’

Loading...

| London

Japan has often had to face the power, peril, and pain of earthquakes. But this week, its national politics were hit by an electoral quake: a breakthrough by a brash, Western-style populist party modeled on Donald Trump and his MAGA movement.

How that impacts Asia’s most stable democracy will become clearer only in the weeks ahead. Sunday’s vote was a mid-term election for the less powerful, upper house of the legislature. And the Sanseito party, while surging, is still only the fourth-largest bloc in that chamber.

But the message for mainstream politicians in other democracies worldwide is unmistakable.

Why We Wrote This

The populist surge on the right is a familiar electoral feature across the West. Gains by the far right in recent elections in Japan show its global appeal.

Anyone who has lived and worked in Japan, as I did as an English teacher after college, will understand the extraordinary nature of Sanseito’s breakthrough. Japan is a country steeped in tradition, where an emphasis on order and politeness, and a staid approach to politics has seen the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) govern for all but a handful of the last 70 years.

The fact that MAGA-style messaging has found fertile ground even there – on “wokeness” and the “deep state,” LGBTQ+ issues and COVID vaccines, globalism and, above all, immigration – has underscored the international reach of this new brand of insurgent populism.

It has also provided an insight into why so many centrist politicians – in America and across a range of European countries – have been struggling to find an effective response.

It’s that while policies matter, the tougher challenge is to answer the visceral appeal of the populists and to reengage with voters who feel economically stuck, unhopeful about their future, and unwilling to trust the same old politicians to improve things.

Sanseito’s leap from a single seat in the upper house to 14 seemed less about policy than emotional connection.

Its charismatic leader, Kamiya Sohei, did make immigration a focus of his calls to “put Japanese people first.” But while Japan has indeed been accepting more immigrants to help power a stagnant economy as its aging population exits the work force, the overall numbers are still tiny by Western standards: under 3% of the population.

The power of Mr. Kamiya’s appeal, and of his party’s campaign, rested largely on their challenge of the accepted norms of Japanese politics.

Major parties have long relied on large-scale campaign contributions, and the LDP was only recently mired in an illegal fundraising scandal. Sanseito drew its support from smaller, individual donations.

Election campaigns have traditionally featured serious-sounding politicians making serious pronouncements and engaging in serious policy debates. Sanseito thrived through YouTube, TikTok, and social media posts – including a hefty helping of conspiracy theories and scare stories around an “invasion” of immigrants, sometimes debunked by mainstream media fact-checkers, but to little effect.

Mr. Kamiya and his party succeeded in positioning themselves as the voice of an wide array of voters united in mistrust of, and sometimes anger at, politics-as-usual.

The online messaging appealed particularly to young urbanites. But the country’s stagnant economic performance in the 1990s and early 2000s has also left many middle-aged Japanese discouraged, disaffected, and open to Sanseito’s norm-busting assault on the established parties.

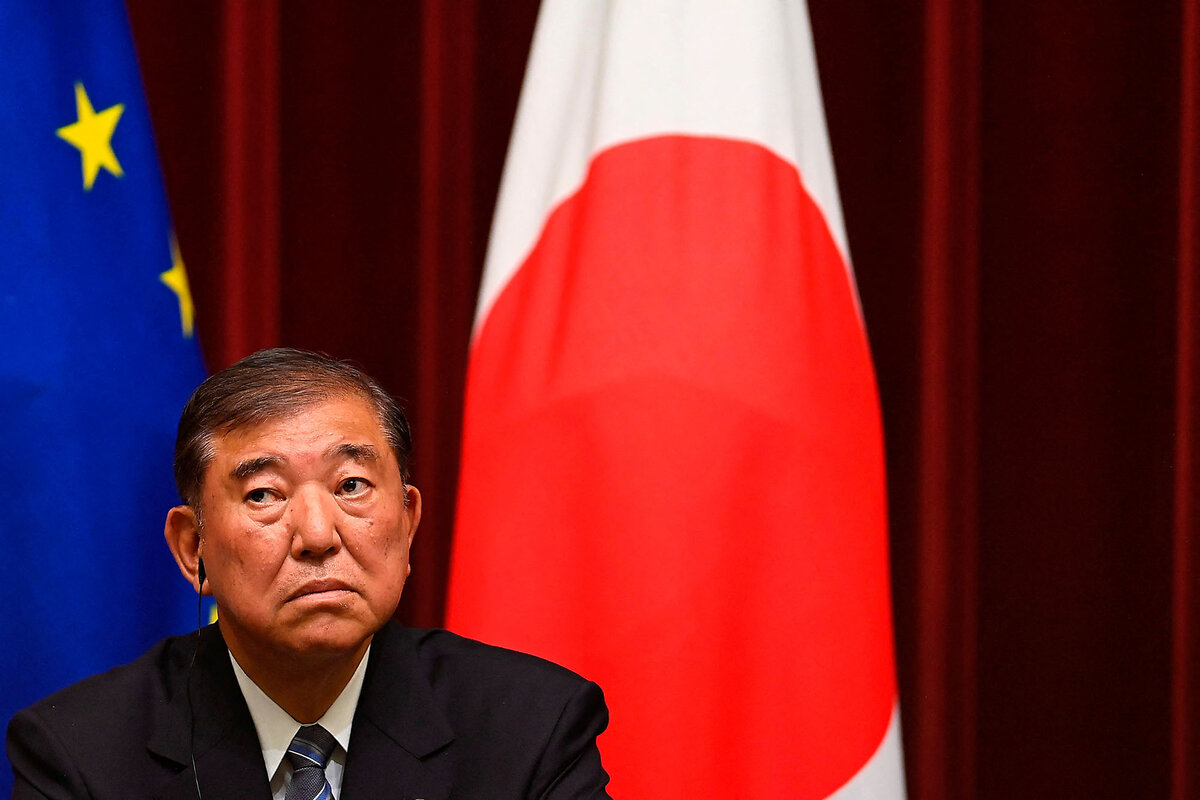

Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru and his LDP now face much the same challenge as Mr. Trump’s critics and opponents in America, and center-ground leaders in Europe: how to prevent a populist surge from becoming an irresistible tide.

In Europe, the initial instinct of many mainstream conservative parties, especially on the emotive issue of immigration, has been to try to steal the populists’ clothes – either by adopting tougher border and asylum policies themselves or giving the insurgent parties a voice in government.

Neither seems to have helped their own political fortunes. Long-established center-right parties have been shrinking, as their voters abandon the converted hardliners for the genuine article.

The other option – typified by the unapologetically noncharismatic leaders of Britain and Germany, Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Chancellor Friedrich Merz – has been to persuade the electorate they’ll work hard to deliver sustainable policy results on issues like immigration, and above all, economic growth, in a way that tub-thumping populists simply cannot.

On that, the jury is still out. Both leaders will believe they have time to win the argument, however, since their next general elections are still several years away.

That may also be the hope of Prime Minister Ishiba, a non-flashy politician in the mold of the British and German leaders, who took over the LDP in the wake of the fundraising scandal.

Japan’s next general election is set for 2028.

Yet he could be gone far sooner – pushed aside by his party over the ruling coalition’s loss of its upper-house majority, and Sanseito’s gains, in Sunday’s election.

In the short term at least, he has vowed to stay. He may draw encouragement from this week’s announcement of a tariff deal with the U.S. Its reported 15% levy of Japanese exports is less than businesses had feared.

But for Mr. Ishiba and all politicians on the center ground, Sanseito’s dramatic ascent is a reminder that any effective pushback will have to go beyond individual policy wins.

In order to reclaim lost voters, they’ll have to match the powerful appeal of the populists with a credibly compelling narrative of their own: that the old-style politics still works, and that it can make their lives better.