Trump has threatened mass deportations. Mexico prepares for mass reintegration.

Loading...

| Mexico City

Tucked on a quiet street in central Mexico City is a gathering space for pochos.

Historically speaking, the slang word for a Mexican who has lived a significant part of their life in the United States isn’t kind. It translates directly to “rotten fruit” and implies both poor Spanish skills and a perceived superiority complex.

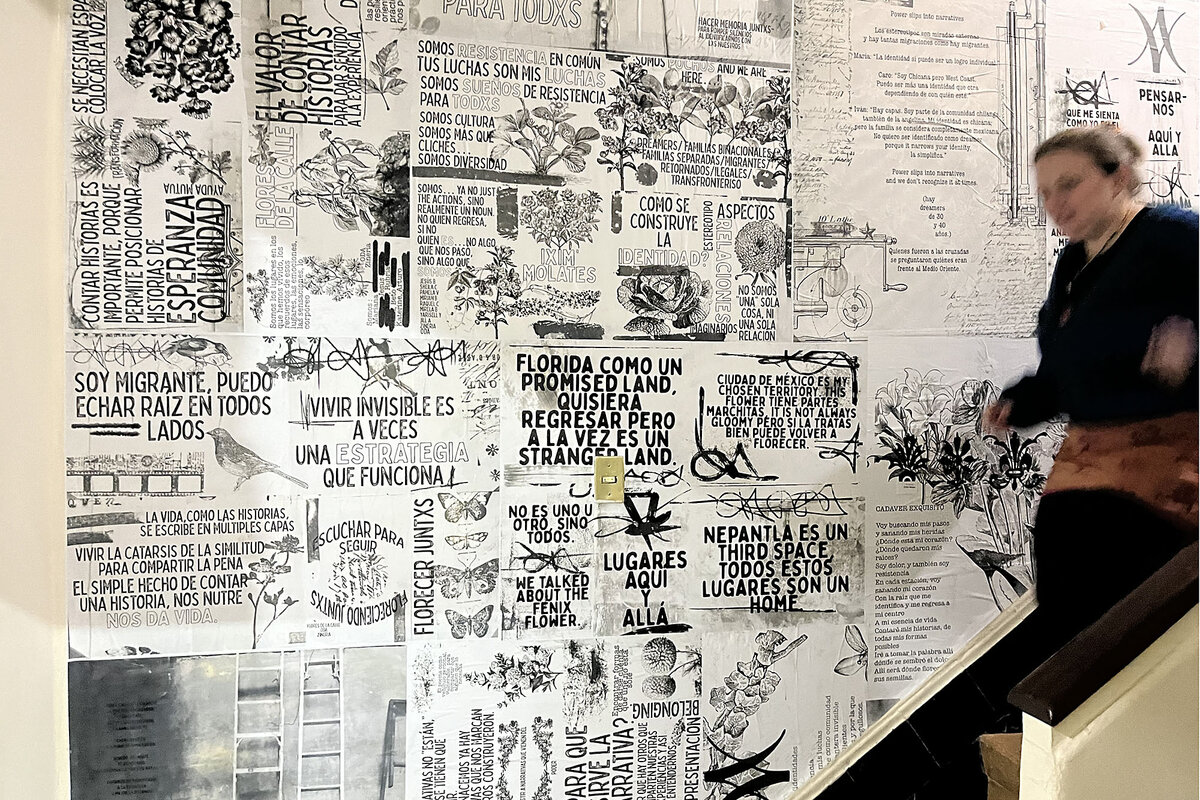

But in a small conference room at the “pocha house,” a nongovernmental organization is accelerating the work it has done over the past decade to help deportees – and reframe the term pocho into something that means pride, resistance, and resilience. The work of Otros Dreams en Acción (ODA) couldn’t come soon enough. U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has promised to expel mass numbers of unauthorized immigrants his first day in office.

Why We Wrote This

Deportations entail fear and heartbreak. But amid an expected wave of deportees from the U.S., Mexican civil society is mobilizing to lay out a more positive reintegration.

ODA joins other civil society groups across Mexico preparing a massive reintegration effort, by publishing information on how to access schools and jobs, or by working to shape attitudes towards deportees and toward the act of rebuilding lives more broadly. Experts say those efforts are critical at this time of transition since the Mexican government’s response to the uptick in deportations over the past 15 years has been reactionary – and this wave could set records.

“Truly those who take charge of the reintegration of deportees are civil society organizations and family networks, for those who have them,” says Nuty Cárdenas Alaminos, an associate professor at Mexico’s Center for Research and Teaching in Economics whose research focuses on deportation and the reintegration of returnees.

Filling the void

An estimated unauthorized immigrants reside in the U.S., and that’s likely an undercount. If Mr. Trump follows through on his promises, the vast majority of those deported are expected to be Mexican, the nationality of almost 40% of unauthorized immigrants in 2022.

Mexico has experience with mass deportations, as recently as the administration of Barack Obama, whom some referred to as “the deporter in chief” for the estimated 5 million people deported between 2009 and 2017. Mr. Trump in his first term and President Joe Biden also racked up significant deportation numbers at roughly 1.5 million deportees in each four-year term (through fiscal year 2024), according to the Migration Policy Institute. Mr. Biden’s tally is closer to 4.4 million if including Title 42 expulsions during the pandemic.

One lesson learned for researchers – and the Mexican government – over the past 15 years has been that preparing for deportations needs to begin long before people start arriving back.

The more than 50 Mexican consulates in the U.S. have reinforced programs over the past several years offering legal assistance to their citizens. And in recent weeks they’ve created links between schools and legal firms, and contracted more than 2,500 legal professionals to support consular services for Mexicans in the U.S. without authorization or in legal limbo.

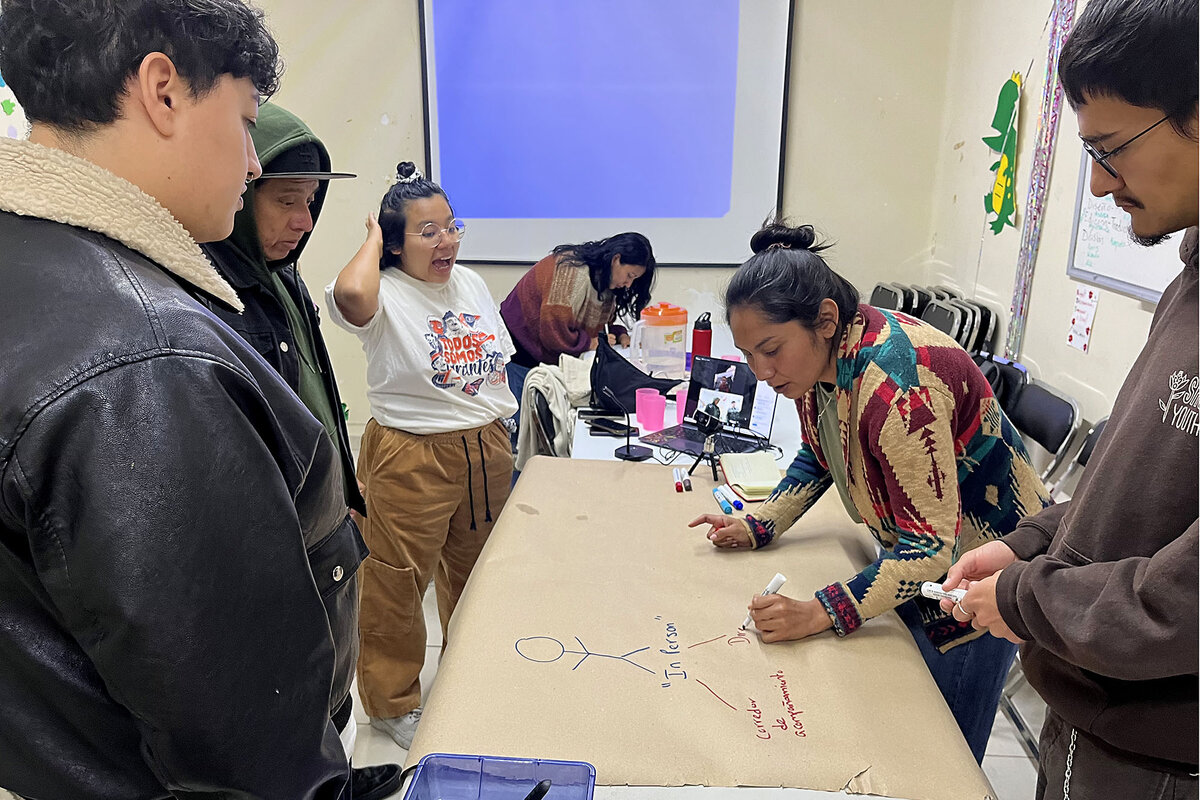

But inside Mexico, state and federal governments have provided little training or policy proposals. That’s why ODA has called a meeting on a chilly evening in late December, with butcher paper and markers to brainstorm ideas in English and Spanish. The attendees include those previously deported or forced to return to Mexico, academics and professionals, and a slew of volunteers. They discuss publishing information packets outlining basic first steps for reintegration into Mexico or creating a registry of returnees willing to help new arrivals with schools and jobs in cities across Mexico.

The group, formed 10 years ago, last year successfully advocated for lifting the Mexican government requirement for school transcripts to be officially stamped before giving children from abroad the right to enter Mexican public schools – a barrier that had vexed returning families, says Leni Álvarez, the ODA co-director.

She was brought to the U.S. at age 2 and grew up saying the U.S. Pledge of Allegiance every morning at school. When her family had to return to Mexico amid pressure on unauthorized immigrants and the financial crisis, she recalls a bureaucratic nightmare trying to get admitted to the Mexican school system, and a general sense of not belonging in the country of her birth.

So tonight her focus is on action. “How can we attend to this population this time around?” she asks the group gathered. “And in a sustainable way, so that we don’t burn out?”

Beauty in rebuilding

This question echoes across Mexican society. Deportation has turned one couple in Mexico into social media influencers poised to help those now at risk of being kicked out of the U.S.

In May 2020, Candice and Fidel, who only use their first names for privacy, started sharing on social media details of their family’s experience rebuilding their lives in Mexico following Fidel’s 2016 deportation from the U.S. Candice, an American, fields many logistical questions – about 50 to 100 daily. But she also shares across her platforms under the name _laguerita70 stories of the family building its “forever” home in the central state of Puebla where Fidel left for the U.S. when he was 17. She runs errands with their three children (two of whom were born in Mexico) and learns to bake traditional Mexican treats.

“My goal is just to be there” for families experiencing deportation and putting down new roots, she says.

That psychological support – for returnees and Mexican society – can be just as important as the logistical. ODA has experimented with free mental health services for deportees who often face depression from the displacement. Humanitarian groups are also holding events to educate local communities that deportees need a helping hand – not stigmatization as criminals.

The pochos at this ODA strategy meeting are prepared to help in the work of shifting attitudes because they have the lived experience, they say. “The biggest tool of this new [Trump] administration is to terrorize and create uncertainty,” says one young returnee in a room with a sign on the door that reads “Resistance.” “We have to stand up to these challenges with creativity.”

Her fiery words are met by a sea of nodding heads. This is a group of individuals who say they are ready to stand up to the challenges coming their way like true pochos leaning into pride, resistance, and resilience – and a deep understanding of what it’s like to live both here, and there.