Trump reignites South African debate over white farmers: Persecuted or privileged?

Loading...

| Johannesburg

Zenia Pretorius was still in bed one Saturday morning in February when her phone started lighting up with excited messages from friends and family.

She soon learned why. American President Donald Trump had just signed an executive order offering certain white South African farmers – her family among them – refugee status in the United States.

It was “like a miracle had been dropped from the sky,” she recalls.

Why We Wrote This

Donald Trump says white South African farmers are victims of persecution. In South Africa, the reality is more complex.

Over the previous year, her family had clashed with the Black community living alongside their onion and potato farm in the country’s northern Limpopo province.

So when Mr. Trump asserted that Afrikaners – the descendants of mostly Dutch colonists – were fleeing “race-based discrimination,” the American president’s words struck a chord with Mrs. Pretorius.

Since he took office in January, the president and his allies, including South Africa-born adviser Elon Musk, have acted as a global megaphone for the fears of farmers like the Pretoriuses – that white people have no place in the new South Africa.

“Staying is not an option,” Mrs. Pretorius insists.

But for most South Africans, the idea that Afrikaner farmers are desperate to flee is “mad,” says Nick Serfontein, himself a white commercial farmer who also served on President Cyril Ramaphosa’s advisory panel on land reform.

To do so, after all, would mean giving up immense advantages. “It is ironic that the executive order makes provision for refugee status in the U.S. for a group in South Africa that remains amongst the most economically privileged” in the country, wrote the South African government in February.

Some 70% of South Africa’s commercial farmland is owned by its white minority, who make up just 7% of the population. They have, on average, an income than Black South Africans.

“I honestly do not believe that any established farmer is going to give up and leave for the United States,” Mr. Serfontein says.

Righting wrongs

For more than a century, commercial farming in South Africa has been dominated by people like Mrs. Pretorius’ husband, Ludwich, whose farming lineage stretches back several generations. The profession, she says, is “in his blood.”

But it got there in large part because of colonial and apartheid policies that reserved nearly all of the country’s farmland for white people. When South Africa became a democracy in 1994, to keep the peace and protect the country’s economy, Nelson Mandela’s new administration did not take away that land, as happened in neighboring Zimbabwe. Instead, it began to chip away at the inequitable balance of land ownership by, among other things, buying up farmland from white farmers and selling or leasing it to Black ones.

But progress has been slow, points out Wandile Sihlobo, chief economist at the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa. His research found that only of land has been redistributed in the past 30 years.

Still, advocacy groups for white farmers have long argued that they are targets for violent crime and they are being murdered at disproportionate rates, .

These numbers caught the attention of Mr. Trump . More recently, he and Mr. Musk latched onto news that South Africa’s government had passed a law allowing authorities to take land without compensation in narrow circumstances, such as when it , and the owner refuses to sell.

Mr. Sihlobo says the policy poses few concrete risks to farmers. To date, no farms – white-owned or otherwise – have been seized.

But farmers like Mr. Pretorius claim they have felt South Africa’s shifts in other ways. Last year, his family says, they began clashing with residents of the Black township that backs up against their farm. Mrs. Pretorius says her neighbors stole fencing, grazed their animals on the family’s land, and made threats against them. The Monitor was not able to independently verify these claims.

Eventually, the family decided to give up the farm, and began looking for options to emigrate.

Then came Mr. Trump’s offer.

The next generation

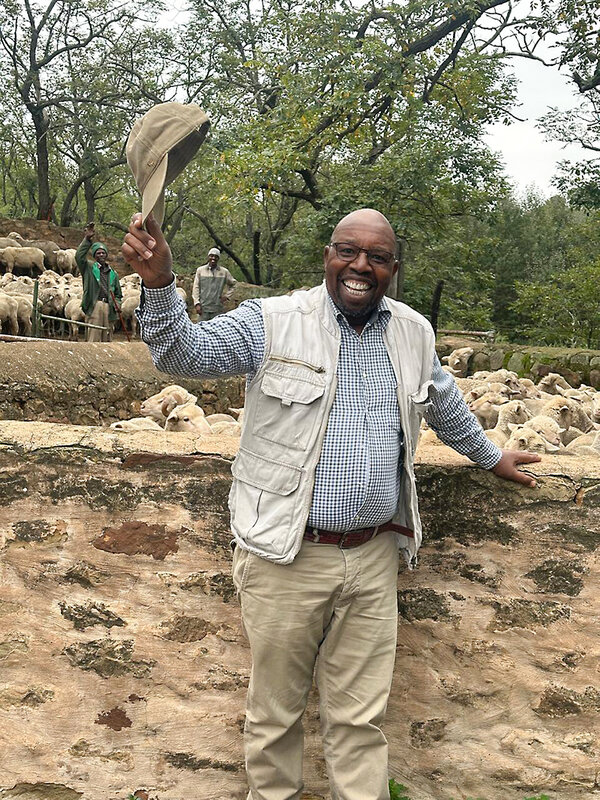

On his farm in Sterkstroom, in the rural Eastern Cape province, Aggrey Mahanjana sees the situation for farmers differently.

He was a communal, subsistence farmer when, in 2009, he was invited by the government to lease a 13,000-acre farm it had purchased from a white family.

The lease gave him a leg up, but the farm didn’t have any tools or machinery. Mr. Mahanjana says his early years on the farm were “very difficult.”

Today, however, he has 500 cattle and thousands of sheep, and his face lights up when he speaks about them. The farm is a commercial success. But he is acutely aware of how rare that is.

As evidence, he points to his local WhatsApp group, where about 70 farmers in the area share tips and exchange friendly banter. Sometimes, they invite each other to braai – a South African barbecue – united in their passion for farming. But in the group, and at every gathering, Mr. Mahanjana says he is the only Black face.

The Pretorius’s problems are also not unfamiliar to him. He says he, too, has been a victim of theft and vandalism.

But Mr. Mahanjana is determined to keep going. He hopes to one day own his land outright. He dreams that his son will one day take over the farm, armed with something he never had: generational wealth and expertise.

Ready to go

Meanwhile, the Pretorius family is preparing for what they hope is their imminent departure for America, although there’s been scant detail on how to actually apply for Mr. Trump’s offer.

In March, The New York Times that “ad hoc refugee centers” will soon be set up to process requests. A State Department spokesperson confirmed to the Monitor that the U.S. Embassy had begun scheduling “informational interviews.”

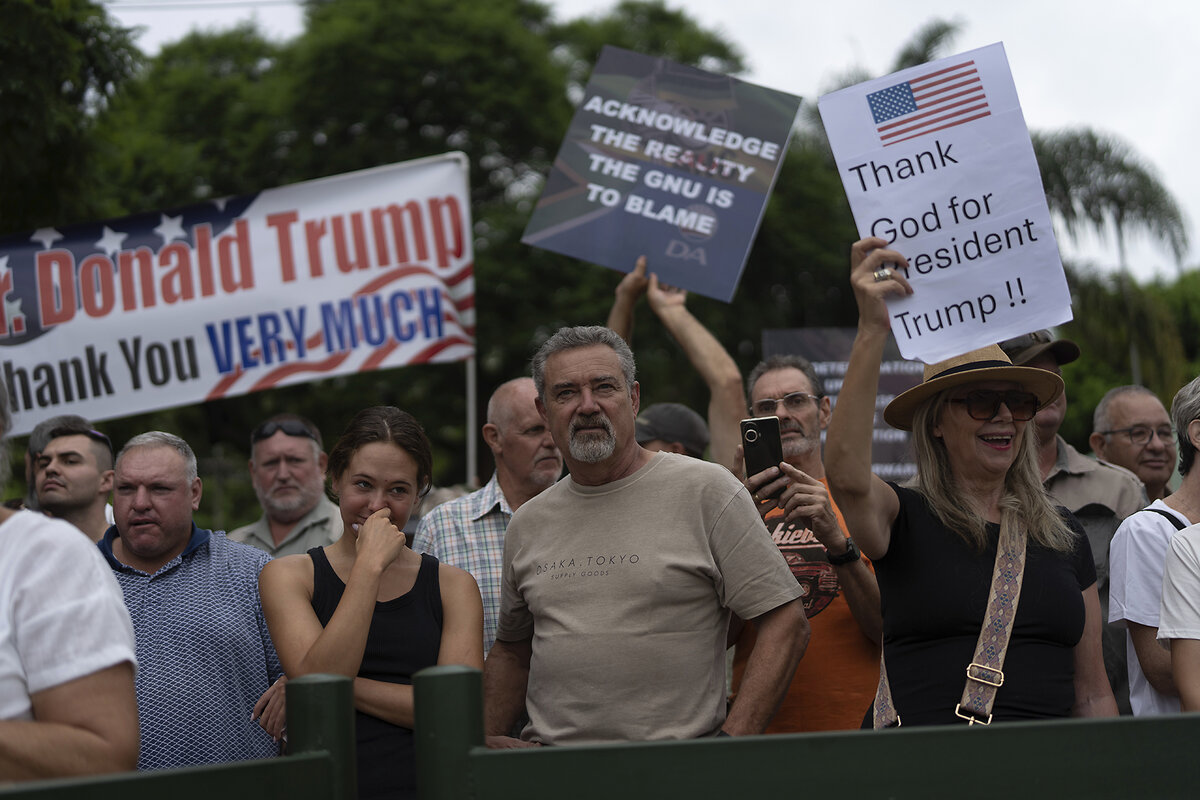

Meanwhile, Mr. Trump continues to voice his support for white farmers. On April 12, he that he would not attend the G20 summit in Johannesburg later this year because “they are taking the land of white Farmers, and then killing them.”

Mrs. Pretorius says she is buoyed by Mr. Trump’s statements. She might not know exactly when she is leaving for America, but she isn’t waiting around. She has already started selling the family’s furniture to pawnshops in town.