No naira in Nigeria: What’s a cashless reporter to do?

Loading...

| Lagos, Nigeria

I slid a mint $100 bill across the counter at a currency exchange shop at Lagos Airport and waited for the attendant to hand me back the equivalent in Nigerian naira. It was Feb. 16, and I had just arrived in Nigeria to cover the country’s much-anticipated presidential election. My mind was spinning with plans to attend rallies, interview voters, and shadow canvassers when suddenly the currency attendant’s voice called me back to reality.

“We don’t have money,” she said, standing in front of boards showing exchange rates for different global currencies. “There’s a naira shortage.”

That was my abrupt introduction to Nigeria’s cash crisis. Caused by a bungled rollout of new banknotes, it had gripped the country for weeks in the run-up to the Feb. 25 presidential election. The crisis is bound to be top of Bola Tinubu’s “do-do” list, now that he has been declared the winner and Nigeria’s president-elect.

Why We Wrote This

Reporting from a foreign country when you have no money is hard enough. Try living there day in, day out when you have no money. Welcome to today’s Nigeria, courtesy of the central bank.

In a heavily cash-dependent economy, the shortage has left people unable to buy basics such as food and water, or to catch buses to school and work.¬ÝFor me, the situation was less dire, but it did require some creative thinking.

After the currency exchange attendant in the airport told me she had no cash, I asked if she had any idea how I could buy a local SIM card without it. She told me to give her the cost of the SIM card in dollars, and then she made an instant bank transfer from her personal account to the SIM card vendor‚Äôs. The vendor slid the new SIM into my phone. Crisis averted ‚Äì for now.¬Ý

“Wasting fuel for nothing”

The origins of this cash shortage stretch back to October, when Nigeria‚Äôs central bank announced that new naira notes would be introduced in some denominations to fight counterfeiting and hoarding, among other reasons. Nigerians had until Feb. 10 to turn in old notes. Most did so, expecting that they‚Äôd get new money right away.¬Ý

It turned out, though, that few of the newly designed notes were available. Banks began severely restricting the amount of cash people could take out of their accounts. Every day, Nigerians thronged to banks and ATMs, forming hourslong queues to try to get at their money. In some parts of the country, angry citizens even burned down banks.

All this was going on at a crucial moment in Nigeria’s history. After years of insecurity, rising unemployment, and a failing economy, Nigerians were about to vote in a presidential election that many hoped would turn the country around. Instead, the cash crisis was exacerbating the problems.

Again and again during my election reporting, people I interviewed spoke unprompted of how much pain and anguish it caused them.¬Ý

Austine Ajime, who drives a tuk-tuk, known locally as a keke, told me business was way down because people didn’t have the new notes to pay for trips. Some, he added, might have had money in their accounts but they lacked smartphones to do cashless bank transfers.

¬Ý‚ÄúWe have just been driving up and down wasting our fuel for nothing,‚Äù he said outside a gas station in Ikeja, an area of Lagos, where he was waiting for passengers.

Usually, Mr. Ajime makes about 13,000 naira ($28) a day, but with the money shortage, he‚Äôs been earning less than 8,000 ($17), most of it paid by bank transfers. That means his earnings are locked in the same limbo as his customers‚Äô. He can‚Äôt buy groceries for his family, for instance, because most of the food sellers he purchases from deal in cash.¬Ý

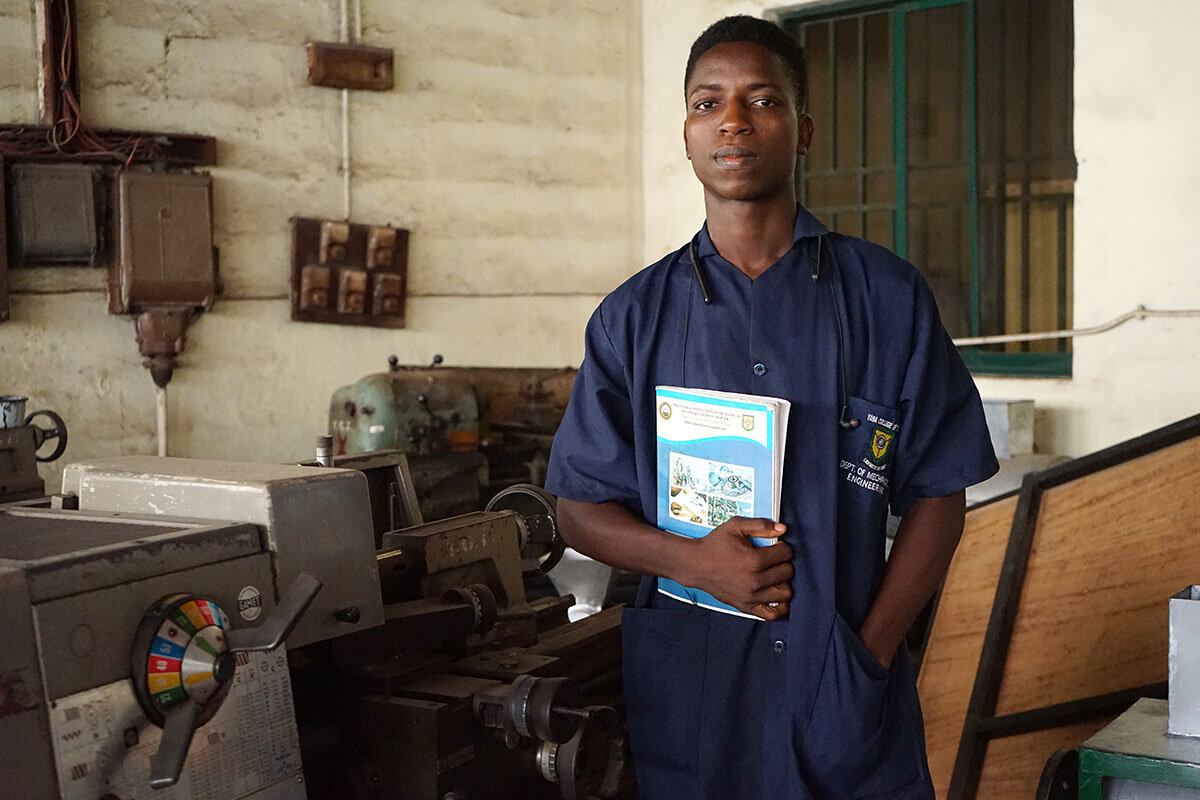

At Yaba College of Technology in Lagos, I found a handful of students sitting outside a classroom chatting. One of them, Genesis Kuba, told me that out of his class of 160, only these few had been able to make it to school that day. Others didn’t have cash for the bus fare. He feels the government has mishandled the currency problem and, like with many other issues, he says, it hasn’t been transparent.

“We just want them to be truthful,” he says. “If the country is in a bad condition, tell us it is in a bad condition.”

“Mobile money” saves the day – for some

As with many crises, Nigerians are finding ways to get by. Those who can pay for goods with banking apps on their phones. Others use debit cards. But in a country where only 45% of adults had bank accounts , such methods exclude most of the population.¬Ý

So, many people without bank accounts have started to use ‚Äúmobile money,‚Äù a service popular in many other African countries that allows users to keep and send money from a digital ‚Äúwallet‚Äù on their phone. The value of mobile money transactions has , to $5.4 billion, since the currency change was announced.¬Ý

After failing to get naira at the airport, I spent the next 10 days figuring out creative ways to pay my reporting expenses. Luckily, my hotel agreed to accept dollars. The Nigerian journalist I was working with paid for our meals and cab rides through bank transfers, and I gave him the equivalent in dollars. But sometimes, not having cash made it harder to bond with my sources. One day, for instance, I spoke to a man selling fried dough on a roadside. Normally after an interview like this, I‚Äôd buy a snack from his stall in appreciation. But without cash, I couldn‚Äôt.¬Ý

It was tiring, and when I left the country on Sunday, the crisis still seemed far from any resolution. As my taxi driver approached Lagos Airport, he veered suddenly onto a different road. He had to take a longer route, he explained to me, to avoid a toll. He didn‚Äôt have any cash.¬Ý