Spring break in Puerto Rico? After María, that means 'rebuild,' not 'relax'

Loading...

| Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve and Barranquitas, Puerto Rico

Mallory Gibson, a music-business major at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC), has spent her junior-year spring break surrounded by sand, surf, and palm trees. But her experience has been pretty far from typical.��

“This is exactly what I wanted to do,” says Ms. Gibson, who moments earlier put down a nearly two-foot-long machete that she was using to whack apart a fallen palm tree. She’s covered in a thin film of dirt and, like everyone else here, drips sweat under the midday sun. Just a few hundred yards away the Caribbean laps the sandy shore of the Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve, but she won’t dip her toes in the water until her seven-hour work day wraps.

“We’re tackling a small drop in the large ocean of things that need to be done” to help Puerto Rico get back on its feet, she says.��

Gibson is the co-leader of a 22-person team from her university that traveled to Puerto Rico to volunteer six months after hurricane María, cleaning up debris and helping regenerate parts of the forest destroyed by the Category 4 storm.��

These college students aren’t alone in eschewing traditional spring break activities like sunbathing and partying to help Puerto Rico recover. From the more than 100 Boy Scouts from across the mainland US helping to rebuild a scout camp in Guajataka to 31 Harvard law students providing pro-bono legal aid and humanitarian work, spring break in Puerto Rico this year is a far cry from lazing on the beach.��

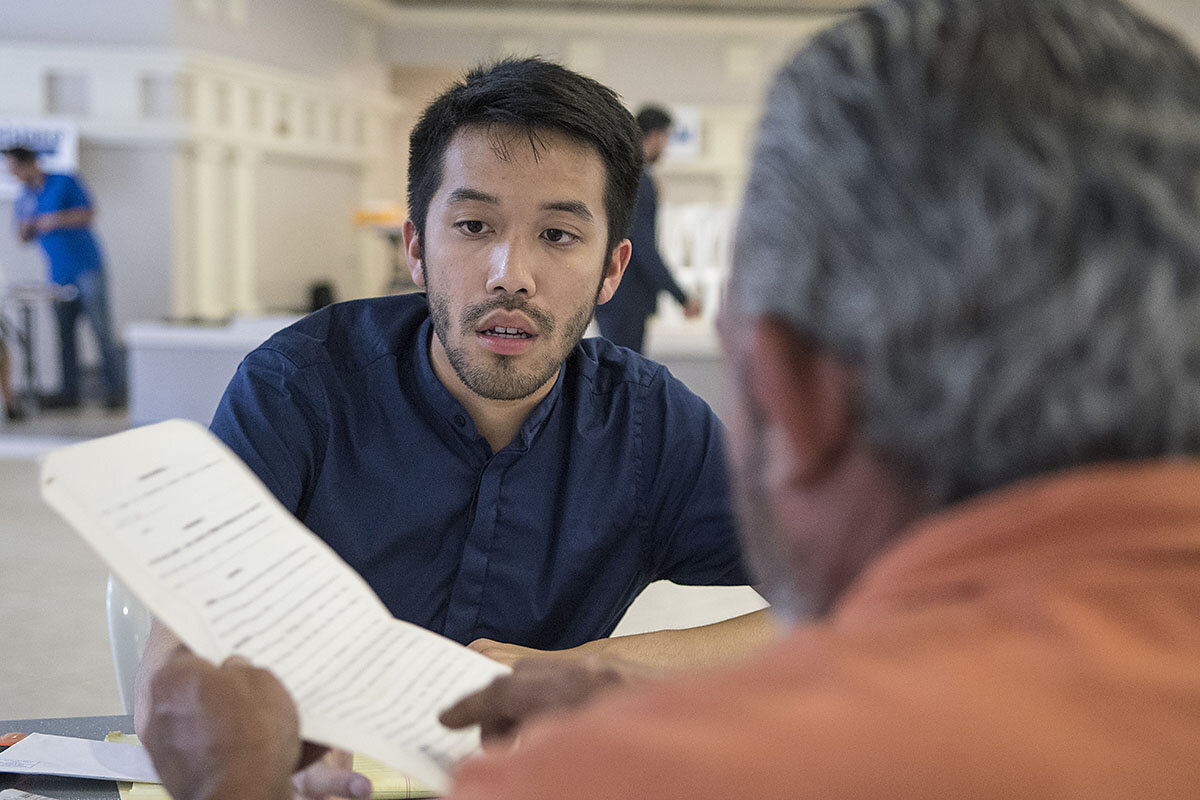

In “school, you tend to forget what real life is about,” says Kevin Ratana Patumwat, a second-year Harvard Law student. He’s come to better understand the disaster, which, as of March 9, still had left nearly 150,000��homes in the dark. “I’ve met people who can’t gather the proper documents [for aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA] because the roof of their house is caved in from María,” he says.

Students dedicating their time off to working with communities in need bucks the labels and stereotypes of selfishness thrown at young people. And it’s part of a larger trend in the United States that’s slowly grown over the past 25 years: students using time off to serve in a way that builds community engagement, empathy, and leadership.

“We meet students really interested in getting involved in things bigger than themselves,” says Samantha Giacobozzi, executive director of Break Away, a national organization that trains students at universities across the country to organize and execute alternative breaks.��

“They may still be taking selfies, but they’re really remarkable in the ways in which they get involved” in their communities and current events, she says, referring to both the notable uptick in alternative breaks over the past decade and youth-led movements like activist for gun control after the Parkland, Fla. school shooting. “Because they’re plugged in [online], they know a lot about what’s happening in the world around them.”

Working vacation

Two students in floppy sun hats heave part of a tree trunk onto the back of a flatbed truck on a recent Tuesday afternoon. They high-five and giggle before turning around to pick up another load.

The nature reserve where they’re volunteering to clear out palm trees and storm debris in order to plant native-tree saplings is on the eastern coast of the island, about 20 miles away from where María first made landfall. The trees will help revitalize parts of the reserve that were destroyed by the hurricane, and could one day serve as an additional natural barrier to protect locals from battering storms.

“The work they’ve done in two days would take us about 1-1/2 or two weeks to complete,” says Antonio Bulnes, a reserve staff member working with the students. The nongovernmental organization Para La Naturaleza, which manages the reserve, has a goal of planting 1 million trees in the wake of the storm. “Since María, we’ve needed more help than usual,” says Mr. Bulnes.

Robin Chadwick, a junior studying nursing at UNC, was feeling frustrated after hurricane María. “I don’t like how the government handled the response,” she says. “I kept seeing news stories about how there wasn’t enough support or how people are still living without water and electricity.” She felt helpless, she says.

The storm caused roughly $100 billion in damages to Puerto Rico, exposing deep-seated challenges like an out-of-date power grid and flimsy home construction. Even power restoration is still considered in the “emergency” phase, just three months before hurricane season will rear up again.

When Ms. Chadwick learned about the trip via a school-wide email, “I knew I had to do it.” In the past, she spent her spring breaks traveling to cities like New York for fun or working to finance her studies.

Interest in volunteering in Puerto Rico has shot up since the storm, according to Community Collaborations International (CCI), the Nevada-based organization that helped coordinate the lodging, travel logistics, and volunteer itinerary for UNC’s spring break.

“We had groups travel in January and there are a lot of people going this summer – we’ve never had summer projects in Puerto Rico before,” says Steve Boisvert, founder of CCI, which works directly with universities to help organize alternative breaks.

Many point to another infamous storm, hurricane Katrina in 2005, as driving a surge of interest in dedicating vacation to serving others. More than a quarter of alternative break programs operating in partnership with Break Away, for example, were launched between 2002 and 2011, according to a 2016 Break Away report. That’s the biggest period of growth over the 26-year snapshot they track.

Increasingly, there are also requirements in high schools across the country – and expectations from college admission panels – for students to do community service, starting at a younger age.

This generation “has that background and rhythm of commitment to service in their bones,” says Melody Porter, director of the Office of Community Engagement at the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

The term Alternative Spring Break has become a catch-all for service during vacations, an alternative to the party scene long associated with college spring break. What sets a formal “Alternative Spring Break” (ASB) apart from the service trips that religious organizations or youth groups have been leading for decades is the student leadership in planning the work and travel, and the inclusion of active reflection around the experience, says the Reverend Porter, who co-authored a book released in 2015 on alternative spring breaks.

These trips “open up a world that otherwise wouldn’t be available to students: understanding social issues in new ways, developing relationships with people. Our ultimate hope and what we see happen over and over again reliably is that people come to understand themselves and their positions in the community differently” after participating in an ASB, she says. Most schools hold regular meetings in the lead-up to a trip to discuss the project's bigger-picture context, communicate with community partners, and dissect important topics like the risks of “helicopter-ing” in somewhere to try and be a savior, versus working alongside locals who know best what their community needs.��

Listening with respect

Across the island, in Puerto Rico’s mountainous center, Harvard Law students Javier Secaria and Mr. Patumwat��set up shop at a FEMA center in the Centro de Bellas Artes��in Barranquitas. Mr. Secaria puts his orange backpack on one of the many white plastic chairs filling the vast room, and pulls out a small cardboard sign that reads, “legal orientation desk.” Those lining up for help have driven miles along the steep, winding, one-lane roads to come here today.��

The first- and second-year law students are accompanying Walter H. González Collazo, a lawyer with The Foundation��Fund for Access to Justice��in Puerto Rico. Mr. González and other lawyers like him across the island are working pro-bono to help individuals navigate FEMA bureaucracy in order to try and appeal their denied cases. He bounces between 10 FEMA centers in different small mountainous towns each week, working Monday through Saturday.

Patumwat and Secaria’s work isn’t rocket science. They’re conducting pre-interviews with individuals in order to gather their names and addresses, and to understand what step of the application process might have thrown them off track. But law – even in Spanish – is a language these young students speak, and their legal know-how allows González to tackle nearly double his typical tally of cases each day.��

“In the legal profession, as in others, there’s an ethic we try to teach of service and the idea that with the privileges of education and opportunity come a responsibility of service to others,” says Andrew Crespo, an assistant professor at Harvard Law School who is Puerto Rican. He helped launch the Hurricane María Legal Assistance project last fall.

“You don’t need specialized skills to help. I’ve realized if you are respectful and if you’re an active listener, you can give someone dignity,” says Patumwat. “And when someone feels abandoned after a storm like this, just listening can really help.”