Puerto Rico's children: a focus of concern ... and source of inspiration

Loading...

| Piñones, Puerto Rico

Half the houses in their seaside town may have lost their roofs, parents may have been thrown out of work, and surging waters may have claimed a favorite sofa for watching TV.

But Pablo Rivera and Yadiel Villalona have to admit that, from their perspective as 12-year-old boys, there are advantages to be seized upon in the aftermath of hurricane Maria.

Like the fact that days on end without school means more time to practice three-point shots and the quick breakaway on the local basketball court.

“My heart was beating fast during the storm, but our building was OK and now I’m fine,” says Yadiel, who lives in a public-housing high-rise in this poor town known for its beachfront seafood stalls.

His friend Pablo had a rougher experience with Maria – “Our roof didn’t blow away, but water came in anyway and we lost pretty much everything,” he says – but he too takes a dismissive approach to the calamity that beset Puerto Rico.

“We helped clean up the court three days after the storm and we’ve been playing almost every day since,” says Pablo. Adds Yadiel: “I’m in no hurry to go back to school, I prefer playing basketball.”

As 12-year-old boys just about everywhere seem to know instinctively, you’re better off not to let your guard down, in life as on the basketball court – so there may be a bit of adolescent bravado tucked into Pablo’s and Yadiel’s words.

But as Puerto Rico’s recovery gradually shifts from emergency response – getting food, clean water, medicine, and the much-coveted blue plastic “FEMA tarps” to communities that still have little or none – to more long-term concerns, educators and child psychologists say they’re keeping an eye out for signs of the emotional toll the island’s devastation may have taken among children.

“We’re still pretty much at the first stages of response, basically assuring that families have what they need to survive, but even as we do that we’re watching for the emotional vulnerabilities that this kind of disaster can cause, especially among children,” says Aurinés Torres, a community sociologist from the University of Puerto Rico (UPR).

“It can really shake children’s foundations and sources of confidence,” she adds, “if everything they depend on in the world – their home, their family, their school – is solid one day and turned upside down or even lost the next.”

With her own normal routine of teaching community intervention at the university’s medical center disrupted, Dr. Torres is out in towns like Piñones, working alongside groups of doctors as they provide medical services. Hearing the anxieties of the mothers and grandparents (and kids) she meets, Torres can better assess the kinds of mental-health services Puerto Ricans will need in the months ahead, she says.

One of the groups Torres is piggybacking with is Talleres Salud, a women’s-health support organization that works from the premise that healthy communities start with healthy women.

“Our motivating principle is that if women are well, their children and their communities are well,” says Jennifer de Jesús, a services facilitator with the organization.

“There is so much stress for women after an event like Maria,” she says. “ 'Where am I going to get food and clean water for my family, how do I keep the kids from getting sick in these very bad conditions, where do I go for any help?’ If we can do things to relieve the mother’s anxieties,” she adds, “her children will feel that relief and they will be healthier, too.”

'What's important hasn't changed'

At the emergency response office in Torrecilla Baja, a half-collapsed neighborhood of Piñones, mothers and grandmothers seeking solutions to a myriad of Maria-spawned tribulations offer a picture of both the trauma caused by Maria and the resilience shining through.

Jannette Maysonet, mother of daughters Leylanis and Amahía and expecting a third child, says she and her husband are trying hard to assure their girls that the important things in their lives haven’t gone away, and that no hurricane can stop mom and dad from keeping them safe.

“We want them to feel as much as like normal life goes on, that despite everything we see around us that what’s important hasn’t changed,” Ms. Maysonet says.

When Amahía celebrated her fourth birthday four days after Maria, her mom didn’t let a knocked-out kitchen and shuttered local businesses deter her: She managed to find a small packaged cake and to put a candle on it.

And when Amahía started waking up at night crying for her father, a first-responder in a San Juan suburb who has been working almost nonstop since Maria, Maysonet settled on a heroic explanation for her husband’s absence. “I told her that daddy was doing his job helping other people, and she has been OK since then.”

Lisette Clemente is also turning bad circumstances into an opportunity.

Having lost her house to the storm, Ms. Clemente has moved in with her daughter – a change that serves as a daily reminder of her loss, but one which also has ended up giving her a sense that she’s contributing to her family in these tough times. She’s taking care of her granddaughter Amaya, since the pre-school she attends remains closed and Amaya’s mother is back at work at a reopened Sam’s Club.

“We’re really trying to show [Amaya] that she is safe and doesn’t have to worry about anything,” Clemente says.

From kids, a sense of solidarity

Indeed, when asked for her thoughts on Maria, Amaya says resolutely, “Maria? Maria went away.” She also happily offers one of the two tiny yellow flowers she’s holding to the pesky journalist peppering her with questions.

What prompted a little girl to share her prize with a stranger may remain unknown, but many Puerto Ricans say they are seeing signs everywhere – in particular among young people – of a desire to give in the midst of so much loss, and to do what one can to help others out.

“It’s quite striking how much evidence we’re seeing of young people and even small children chipping in to help their home and their communities recover,” says Yolanda González, an assistant professor at UPR’s Graduate School of Education. “It shows that even at a young age there’s a sense of solidarity and some level of understanding that we feel better when we help others.”

In Arecibo, a coastal town west of San Juan, Francis Marciál embodies this spirit as he joins his mother Yanaira Pitre and some municipal workers to distribute a truckload of tarps to residents whose roofs were carried away by Maria’s winds.

“I like helping other people, it makes me feel like I’m doing something for Puerto Rico,” says the high school senior aiming to study mechanical engineering. “I know a lot of people say the young people don’t do anything, but I don’t think that’s true. If you look around,” he adds, “you see a lot of young people doing something to help out.”

Professor González notes that hundreds of students showed up spontaneously at the university to help clear debris. As word spread, hundreds more came to pitch in over subsequent days.

Even Pablo at the Piñones basketball court makes the unsolicited clarification that he went to his cousin’s house to help clean up after Maria before he joined friends in clearing the basketball court of debris. “I think that made my aunt happy,” he says.

Focus on helping others

That desire to pitch in is on full display at the Padre Rufo secondary school in the Santurce section of San Juan. Like other public schools on the island, Padre Rufo is closed for regular classes until at least Oct. 23. But in the meantime, the school’s principal has opened her modest campus to elementary school children and teenagers alike as a shelter from what can be the disheartening picture of Maria’s aftermath.

When Padre Rufo first opened its doors about a week after Maria, the focus was on letting kids tell their Maria stories and on assessing their mental state. And there was plenty of hurt and sorrow, judging by the drawings the littlest ones did of their hurricane experience.

One little girl drew a phalanx of menacing visages arriving over a green Puerto Rico, their eyes and mouths wide-open and empty like Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” Another girl colored her Puerto Rico a jarring red and wrote, “God abandoned me.”

But the principal, Beverly Rodriguez, says she decided it was important for the kids to quickly move on from reliving what had happened to understanding that things would get better. “They have a lot to tell, but we didn’t want them to get stuck on talking about the hurricane,” she says. “We want to move on to the future.”

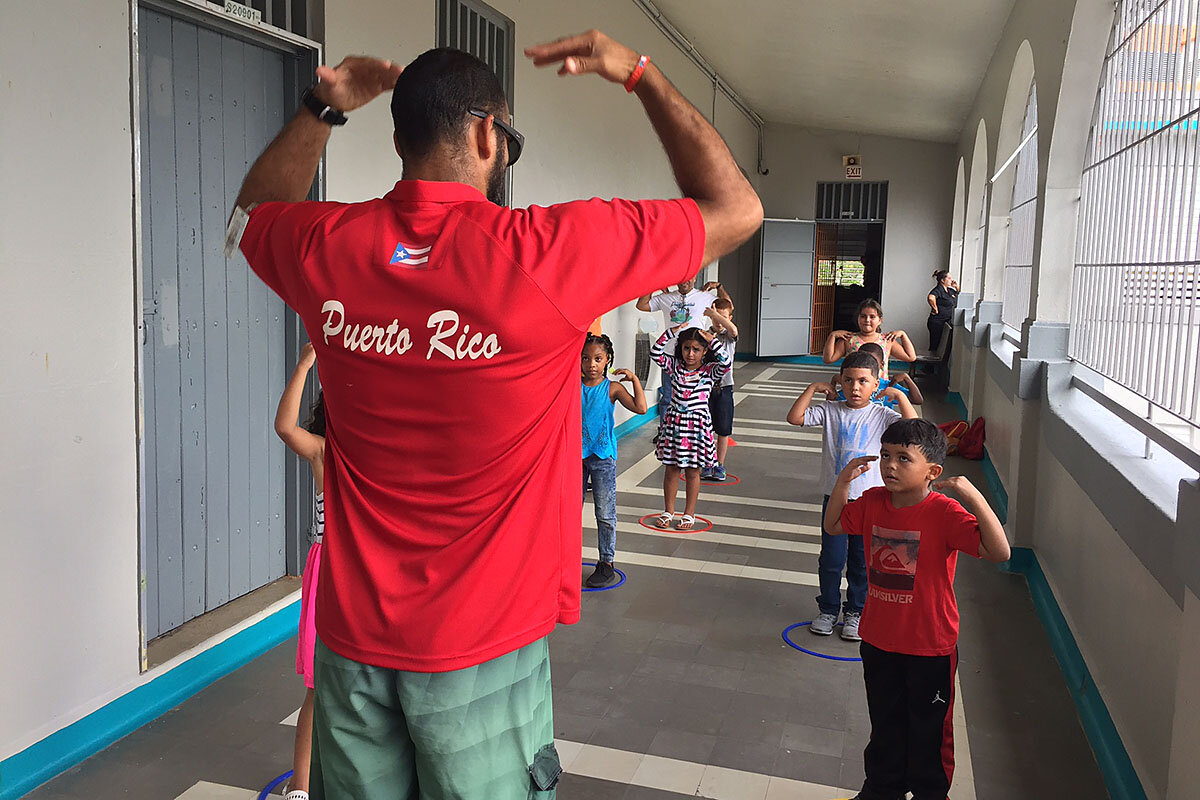

A science teacher takes kids out to the school’s small herb and vegetable garden to show them that all was not lost, that the parsley and basil and spinach are already growing back strong. A gym teacher leads students in calisthenics.

'Puerto Rico will rise up!'

And now Ms. Rodriguez says she’s seeing more signs every day of kids bouncing back and determined to surmount Maria’s challenges. That spirit is captured in another drawing on the school’s bulletin board that boasts the caption, “Maria was a category 5, but Puerto Rico is a category 10!”

One day this week in a classroom of adolescents, clinical psychologist Rosario Gomez, who normally works with at-risk juveniles, brought the kids to their feet with a kind of pep rally for Puerto Rico.

“Maria, Maria, you took away the roof, but Puerto is standing tall!” they chant. “Paint yourself with the colors of hope, so that Puerto Rico will rise up!”

There’s more than happy talk to such exercises, Dr. Gomez says, especially when the fun stuff like the cheers is accompanied by activities that allow for putting the slogans in practice. The kids in the class hand wrote letters to kids who lost their homes and are living in shelters, for example, starting each one with, “My Puerto Rican friend.”

“Kids have a lot of hope, but my worry is that as the long process of recovery from Maria moves slowly on, they lose faith,” Gomez says. “Focusing on helping others and on the small things they can do to contribute can help them keep their hope alive,” she says.

To one side of the boisterous classroom, a quiet Antony Smart offers a confirmation of Gomez’s approach – not to mention an unexpectedly guileless sentiment for a 15-year-old boy.

“I know a lot of people lost a lot in this storm, so it kind of feels good to do something to encourage them,” he says. “I’m feeling my heart when I share from it with others.”