As voters get angrier, local officials bear the brunt

Loading...

| York County, Pa.

When Amy Milsten volunteered to run for school board, she expected to spend five hours campaigning each week. She ended up spending five hours each day.

Her race, in Pennsylvania’s Central York School District, got after the sitting board effectively banned a list of resources on race. As a Democrat running in a Republican district, Ms. Milsten personally knocked on some 1,500 doors – and had some uncomfortable encounters. Some people would listen, but most weren’t interested, she says. Some slammed the door in her face.

While she won the election, the atmosphere hasn’t gotten any better, with controversies over everything from pandemic restrictions to instruction on race and identity still roiling the district.

Why We Wrote This

From school boards to health departments, officials are facing more intense forms of harassment, reflecting the nationalization of local politics. Many say the climate is affecting morale.

“I’m a little afraid for my safety,” Ms. Milsten confesses, as she prepares to take her seat.

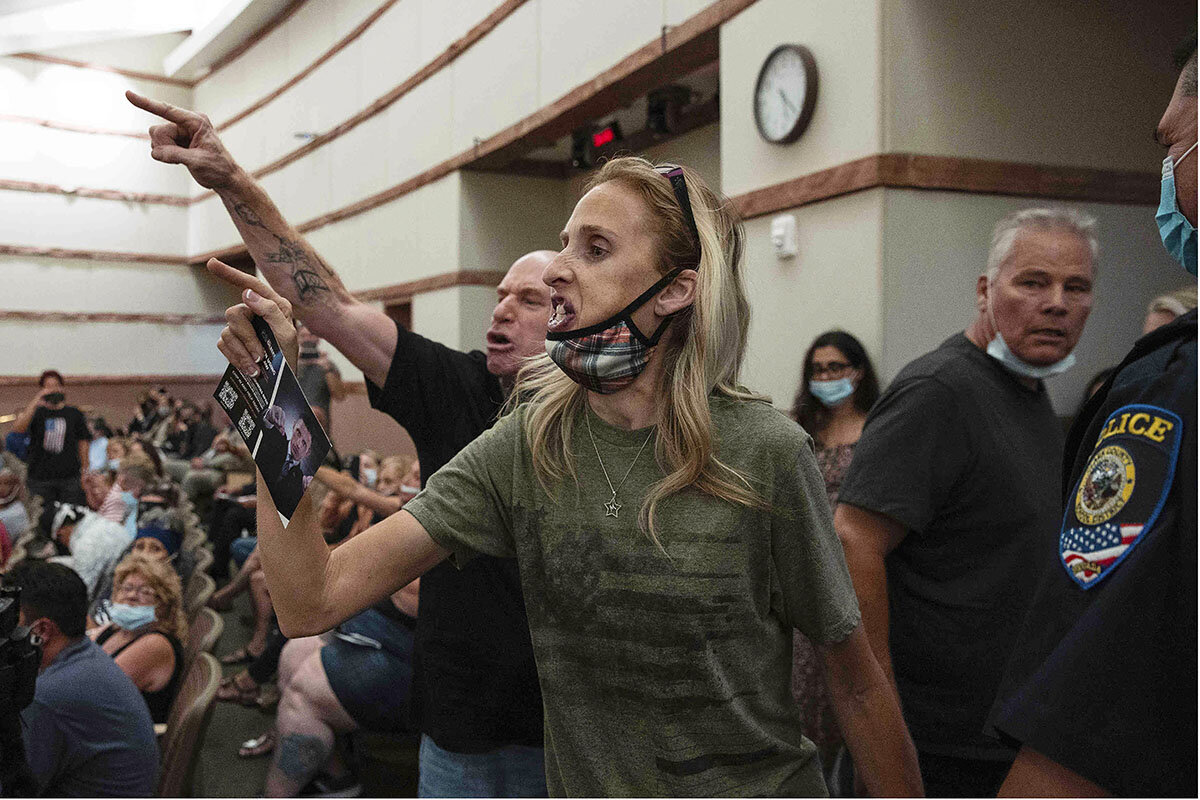

Across the country, local officials like Ms. Milsten are contending with a notable groundswell of hostility. School board meetings are attracting angry, even violent protests. Election officials are refuting heated accusations of fraud and misconduct. Public health departments are fielding menacing emails and phone calls about doing too much to stop COVID-19, or not enough. Many have received threats against their families, livelihoods, or life.

The local level has always been where government connects most directly with communities. Local officials – many of whom serve for little or no pay – aren’t just political actors, they’re neighbors and friends, sitting in the next church pew or standing on the sidelines at a soccer game.

But in such a polarized and toxic climate, that proximity can become problematic – making confrontation more commonplace. Many officials are wondering if public service is worth the hassle, and say the harassment is having a chilling effect on their ability to do their job.

“I feel like if I do open my mouth at one of these meetings and say something that a segment of the population doesn’t agree with, that I could receive veiled threats or actual threats,” says Ms. Milsten.

Loss of trust in institutions

Contentious politics at the local level is nothing new. School boards have long been on the front lines of the culture wars, tussling over everything from sexual education to evolution. Nor is it unusual for, say, city council meetings to grow heated over issues like zoning.

But what seems different today, experts say, is the aggressiveness of voters. Direct threats of violence against school board members led the Department of Justice in October to directing the FBI to address the matter. Critics contend the department was concerned parents.

Over the summer, recorded one in three election officials feeling “unsafe because of their job” and one in five citing “threats to their lives as a job-related concern.” Around the same time, the found that almost 12% of surveyed public health workers had received “job-related threats because of work” and another 23% had felt “bullied, threatened or harassed because of work.” Many �����Ի��� officials have had to hire security details.

, respondents still expressed higher levels of trust in local and state governments than the federal government. But those numbers have fallen to the lowest point in over a decade.

“The degree to which people trust the same institutions has been kind of cratering,” says Lara Putnam, a professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh.

The pandemic seems to have compounded the problem. The approach many states and localities have taken toward COVID-19 has often reflected partisan politics, even though many of those offices are technically nonpartisan. Officials tasked with determining health policies have frequently faced what seem like binary choices, destined to infuriate one group of voters or the other: Should schools be open or closed? Make masks mandatory, or ban mask mandates? Make voting procedures less cumbersome or more so?

“The divisions that you see in Washington, D.C., or at the national level are reproduced in state and local politics,” says Daniel Hopkins, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania.

“It’s calling into question our integrity”

Local officials feel it.

“I’ve been doing this now for 31 years and I don’t remember anything like this,” says Wesley Wilcox, president of the Florida Supervisors of Elections.

Mr. Wilcox knows every election leaves some voters unhappy, and he always expects some frustration in November. But this is new. People have called demanding he put an end to “socialism,” swearing, and saying he’s “been warned” before hanging up. Colleagues who’ve tried to reassure voters about the integrity of the electoral process are being targeted for primary challenges and receiving death threats from constituents.

“This is different, in that it’s calling into question our integrity, our competency,” he says.

This October, Mr. Wilcox and his colleagues issued two memos – �����Ի��� – calling for an end to attacks on election officials. There are 67 election officials in Florida, and about 20% retired in the 2020 cycle. Mr. Wilcox expects more to follow in 2024. Just this summer, a colleague went from celebrating his 20th year on the job to abruptly retiring two months later. The climate, he said, was too difficult.

It’s important to remember that it’s a small share of voters creating that climate, says Susan Ringler-Cerniglia, public information officer for the Washtenaw County Health Department in Michigan. But those voters can have a big impact. Most public health departments are overworked, understaffed, and underfunded, and morale is already low, says Ms. Ringler-Cerniglia. The personal attacks and security concerns are making a difficult situation far worse.

“It hurts,” says Ms. Ringler-Cerniglia. “It’s hard to be accused of those things when it’s like, seriously, my life is in shambles right now.”

It also makes her job more difficult. The Washtenaw department has had to end disrespectful phone calls and disable comments on social media. Interacting with the public has always been a key component of their work, says Ms. Ringer-Cerniglia, but they’ve had to set boundaries.

“We can’t have our staff sitting there literally for hours reading abusive messages, trying to respond to them, [and] having that be completely unproductive,” she says.

Still worth it?

Of course, most interactions with the public don’t go that way.

In Columbus, Ohio, public health commissioner Mysheika Roberts says people in her area sometimes gripe about masking or school policies, but that’s all. It’s been a difficult year and a half for her department, she says, and community support has been crucial.

Still, Dr. Roberts knows colleagues have had it differently. Last year in Columbus, the state health director needed a security detail after people threatened her and protested outside her home with guns. She later resigned.

“I definitely think it impacts the morale,” says Dr. Roberts “Even to me as a leader, it hurts.”

Stories like that hurt everyone, says Mary Kate Anderson Brown, a mother of three elementary school students in Tennessee’s Williamson County.

For the past year, Ms. Brown has organized parents in her area against school closures, mask mandates, and curriculum changes – an unplanned foray into activism that started when she criticized virtual learning on Facebook and her post blew up.

In October, a seat opened on the local school board, and Ms. Brown’s husband was appointed to fill it. They soon gained a personal perspective into what it feels like to be the target of criticism. People started spreading rumors that her family had a hidden vaccine agenda, she says, and they grew concerned for their safety.

“We questioned whether or not it was worth going through, but it comes down to two things: your kids and your community,” says Ms. Brown. “Those two things are about as important to parents as anything in the world. To us, it was worth it.”

To Ms. Milsten, the incoming Central York School Board member, it’s worth it too.

The board’s relationship to families, teachers, and administrators is broken right now, she says, and she wants to help fix it. Sitting members offered her and the other newly elected officials a kind welcome after the race. She hopes there will be room for compromise.

She also hopes people in the county at some point won’t have to think so much about the school board. Local officials aren’t used to this kind of attention, she says. Maybe it would be better if things quieted down.

“I would love at the end of my term, or terms, for someone to look back on the four years or however long on the board and say, ‘Oh wow, I kind of really wasn’t even aware of what was going on,’” says Ms. Milsten. “Things just worked.”