Make a name for yourself with onomastics

Loading...

Last week’s researches into place names derived from numbers turned up reminders that numbers show up in personal names, too.

Mystery often surrounds the way a number makes it onto the map as a place name. But numeric personal names tend to be fairly straightforward: They refer to birth order, traditionally of the sons in a family. Except when they don’t.

Take, for example, the poet ’s eight brothers. The first six had typical Victorian English names: Edward, Samuel, Charles John, George, Henry, Alfred. But the last two were Septimus and Octavius, from the Latin for “seventh” and “eighth,” respectively. It suggests that the Barretts had run out of ideas and so had resorted to numbers.��

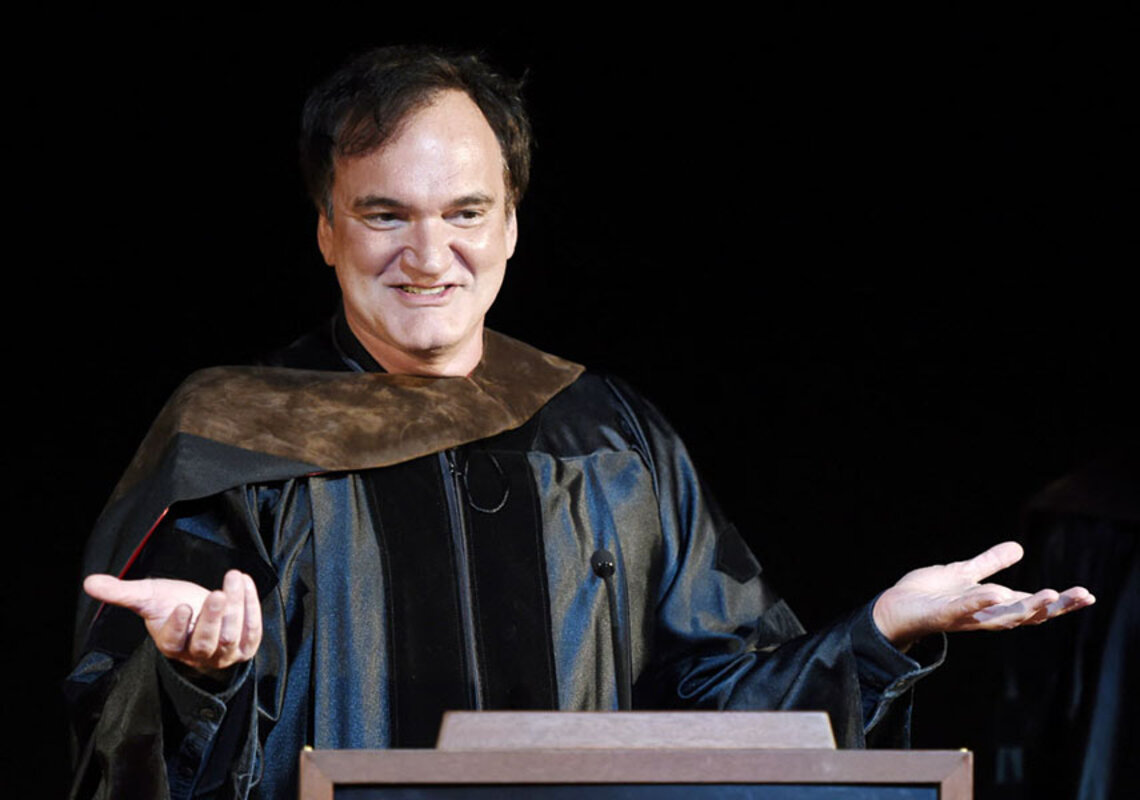

A more recent example of a numeric personal name is that of film director . Was he a fifth son, or at least fifth child, as his name suggests?

Well, no. The Internet Movie Database reports that Mr. Tarantino was “named after” Quint Asper, the Burt Reynolds character in the long-running television series “Gunsmoke.”

There’s a term for the scientific study of proper names: onomastics. I know, it sounds like something hard you have to do at the gym (“Oh, no!”). But it’s from a Greek word referring to “name,” onoma.��

Antonomasia is another word from the same root. It may sound like the name of a hip Spanish film director. But it’s actually a term for a rhetorical device. Merriam-Webster defines it as “the use of a proper name to designate a member of a class (such as a Solomon for a wise ruler); also: the use of an epithet or title in place of a proper name (such as the Bard for Shakespeare).”

Note that this is a two-way device. It was much used by headline writers in the newspaper of my childhood hometown: They would squeeze “Solon” in where “legislator” or “lawmaker” wouldn’t fit. was an Athenian statesman, one of the Seven Wise Men of Greece – with one of the shorter names in that group.��

Onomatopoeia, another word from this same Greek root, means literally “making a name,” according to .��

That “poe” element turns up in our more familiar poet. We may think of poets as contemplative rather than men and women of action. But etymologically, they are people who “make things.”

has come to mean a specific kind of “making a name” – “the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it,” as Merriam-Webster explains (“cuckoo,” “sizzle,” and “crash,” e.g.).��

Several Western languages borrow the same Greek word for this concept. But German has its own term – the perhaps more poetic Lautmalerei, “sound painting.” Students of German know the language often goes its own way, disdaining an international term and using something closer to home.��

I remember being in the supermarket one day when I was living in Germany and noticing “Chinakohl” – “China cabbage” – for sale. Hmph, I sniffed inwardly. In English we call it bok choy.