Rising book bans: Grounds for moral panic?

Loading...

| New York

Whether it’s the depiction in “Maus” of the Holocaust, the discussion about puberty in “It’s Perfectly Normal,” the LGBTQ perspective presented in “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” or the presence of “The Bluest Eye” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” in the high school canon, books in schools and libraries nationwide increasingly have targets on their spines.

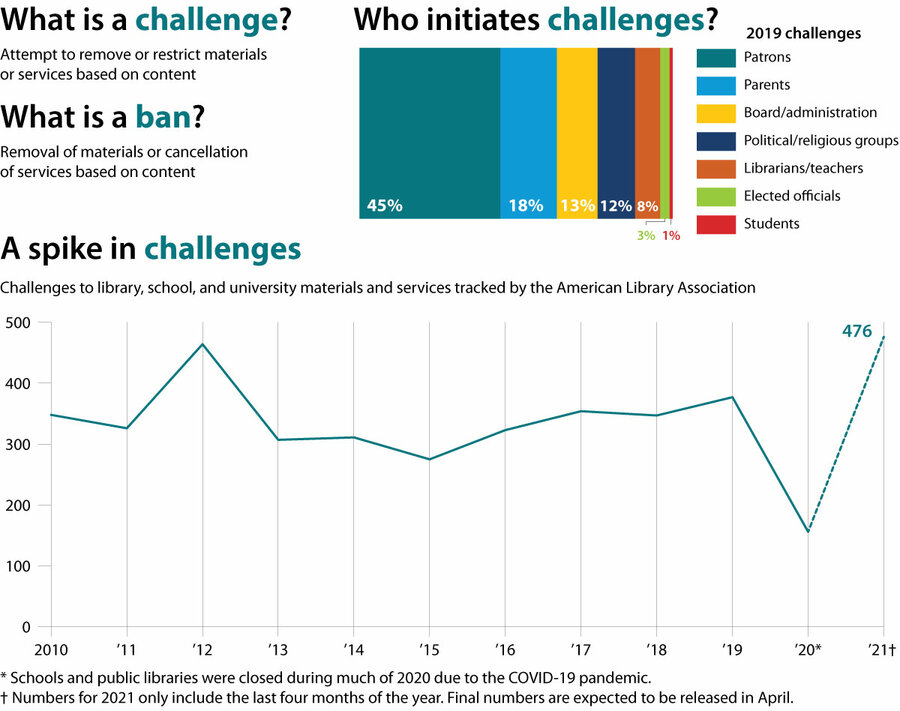

Experts say the challenges – fanned by the heated online “outrage ecosystem” – are growing exponentially. Last year, reports the , brought the highest number of reported book challenges it has tallied in a decade.

Though the full year has not been finalized, there were roughly 476 challenges between September and the end of 2021, compared with 377 total in 2019, the last year schools and libraries were fully open before the pandemic, says Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

Why We Wrote This

Books in schools and libraries increasingly have targets on their spines. The more partisan the battle has become, the more it manifests as a power struggle rather than an effort to find common ground on how best to serve children.

However, caution library scholars, clashes over books, not deliberative conversations make the news. But that doesn’t mean those conversations aren’t taking place in communities across the nation, with challenges resolved or compromises forged before they erupt in acrimonious headlines.

Ten years ago, challenges “were very local,” says Ms. Caldwell-Stone. What happened in one school district did not significantly affect what happened elsewhere. Today, with activists exchanging tactics and information online, challenges are popping up everywhere.

In this increasingly polarized context, says Emily Knox, associate professor in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of “Book Banning in 21st-Century America,” “The books are kind of incidental. What we’re really arguing about is, what does it mean to be a citizen of the United States? How do we want our children to be educated? What do we want to say about our history?”

Book “banning” in the U.S. almost always plays out in the public sector and particularly where children are involved. School curricula, school libraries, and the children’s sections of public libraries have become “contested because we’re trying to figure out what the values of the next generation should be,” Ms. Knox says.

But that is not what the public debate focuses on. As it plays out in the news and on social media, it is an us vs. them battle that makes little room for thoughtful discussion. The more tempers rise and the more partisan the battle has become, the more it manifests as a power struggle rather than an effort to find common ground on how best to serve children.

There are several contributing factors. Sometimes, people argue at cross-purposes because they don’t realize different rules apply to books in a curriculum, in a school library, or in a public library.

For example, when the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee drew international attention when it voted unanimously Jan. 10 to remove “Maus” from its eighth-grade social studies curriculum, it was not removed from school libraries, l Daily Post Athenian.

Books taught in classes are required reading. Since school districts establish curricula, they can determine whether a book should or should not be taught. They evaluate it for age-appropriateness and pedagogical soundness.

Books in school libraries, on the other hand, are not required reading. They are there to support the curriculum but also to fuel a love of reading, address issues of concern to students, and offer a range of perspectives. If it is found to be erroneous, pornographic, or shown not to be age-appropriate, for example, it can be removed.

But in the 1982 landmark case of , the United States Supreme Court ruled that to remove a book based on its ideas and content alone violates students’ First Amendment right to read and be informed. This would apply, for example, to objections to a novel’s depiction of instances of racism or aspects of the LGBTQ experience.

The bar for removal is still higher for public libraries. They serve the community in all its diversity, from age and sexual orientation to ethnicity, race, and political affiliation. In the eyes of the Supreme Court, a public library is a “limited public forum” and “the quintessential locus of the receipt of information.”

This very diversity helps explain why more than half of all book challenges are levied at public libraries, often by “parents wanting to protect their children,” says Paula Laurita, who was executive director of the Athens-Limestone Public Library in Alabama from 2010 to 2020 and has had a long tenure as the ALA’s Alabama chapter councilor. “So what may be acceptable to one family is not acceptable to another family,” she says.

In many cases, parents object to, say, a Gay Pride month display being too close to the children’s section, says April Dawkins, assistant professor in library and information science at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Depending on the library, it might get moved, dismantled, or kept and followed later by a display of, say, conservative authors.

Listening for the success stories

Even when a challenge results in the removal of a book from a public school or library, however, it remains accessible. Other district libraries have it. Bookstores and websites openly sell it. The book is featured during Banned Books Week, the ALA’s “annual celebration of the freedom to read” which features book sales, author’s talks, panel discussions, and displays in bookstores and libraries across the country.

“So, the book isn’t banned, it’s censored,” says Elliott Kuecker, a faculty librarian and researcher at the University of Georgia and author of “Questioning the Dogma of Banned Books Week,” a study published in the journal Library Philosophy and Practice.

When he wrote this in 2018, he says, “my concern was that they were setting up kind of a friend-enemy relationship” because the very word – banning – conjures the image of an attack on democracy. It sets up librarians as heroes fighting off that attack when what they are facing is nothing like the book burnings during the Third Reich or all-out bans imposed by regimes like the Taliban.

Opting for a more accurate description, he thinks, would lead to more productive conversations.

“The ‘censorship’ of an individual book,” says Mr. Kuecker, “is more someone expressing a problem with the morality of a text.” This, he adds, might lead people to talk about what it means “to read an amoral text? Can a text contain morality and ethics, or is it the reader who interprets for that?”

This “friend-enemy” dynamic preempts other conversations as well. For example, Ms. Caldwell-Stone points to the underlying concern of challenges as being “what are young people reading about? What are they absorbing through the words they’re exposed to?”

But, judging from reports of book challenges, the public debate seldom if ever delves into how children process difficult material or whether “young readers are able to discern what the reading [is about] and to make good judgments about it,” as Ms. Caldwell-Stone maintains. Nor is the question of how educators and parents can best guide children examined much in the debates.

Instead, people choose sides over who is better suited to control what children read: parents who know their child intimately or educators who are trained professionals? One side champions greater parental rights, the other counters with students’ First Amendment rights.

And the compromise that many educators and librarians suggest seems to get lost.

“We don’t often hear [about] the really, really thoughtful and successful stories,” Kristin Pekoll, assistant director of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom told librarians during a recent webinar. “That’s because librarians addressed it according to their policies and they’ve had really great conversations with their communities about the resources, and maybe things were deescalated and handled as conversations informally,” she says.

“I believe any parent should be able to say ‘I don’t want my child reading a particular book.’ That’s completely fine,” says Danielle Hartsfield, assistant professor at the University of North Georgia who has written about educators and controversial literature. But parents lack the professional training and knowledge of teachers and librarians to “collectively say ‘no child should read this book.’”

Ms. Knox, as most librarians, prizes the free flow of information, but she understands how fraught this can be.

Efforts to censor what children read “are really demonstrating to us why reading is fundamental. We say things like critical thinking and that kind of thing but, actually, reading changes who you are as a person,” Ms. Knox says.

“Libraries are not labyrinths to truths; they’re gardens of truth,” she says. In online explorations, algorithms progressively channel searches. Libraries, by contrast, are “organized chaos,” says Ms. Knox, where 19th-century Jane Austen sits next to post-modern Paul Auster. “You pick up something here and you pick up something there – that, in fact, makes a library a very dangerous space, because it’s true that your children will stumble upon something that does not necessarily reflect your values.”

And mechanisms exist that can help people talk about how best to help children navigate that space and thrive: detailed and transparent procedures to review whether a particular book belongs in the curriculum or library. This involves a multi-step process beginning with an informal conversation with a teacher or librarian on up through a written complaint based on a reading of the text and ending in a school board or board of trustees meeting.

Did they read the book?

Yet the atmosphere is so charged, the procedures are sometimes bypassed.

Ms. Caldwell-Stone is seeing “school districts that have policies for reconsideration ignoring the policies and removing books from the school library.”

At the same time, Ms. Dawkins reports that complainants “are not receptive to conversation.” Rather than follow the steps, they jump “to the school board and public fora and use inflammatory language” that provokes outrage. “The other thing that happens is [complainants] not willing to read the book in its entirety to see what the merits are,” she says.

The inaccuracies in the challenge of 31 books on the English Language Arts curriculum of the Williamson County School District in Tennessee illustrate Ms. Dawkins’ claim.

is, for example, described as containing the n-word and portraying all white people as angry. In fact, no racial slur is in the text and some of the white characters were supportive of Ruby.

The reconsideration process took six months, during which representatives of parents, teachers, and school board officials read the books and met with complainants. They agreed to remove one book because the curriculum did not allow time enough for it to be properly taught.

The local chapter of Moms for Liberty, an advocacy group that started in opposition to mask mandates in schools and has grown explosively into what it says is a 60,000-plus member force across 33 states, has filed an appeal.

It is impossible to know whether the concerns of these complainants could be assuaged through dialogue. But certainly others’ have.

A case resolved before eruption of headlines

Ms. Laurita used to tell her library staff, “when people come up and start complaining about a book, the first thing to do is take a breath. Don’t get defensive, and listen, because sometimes they just need to hear that their concerns are understood.”

When graphic novels first came out, a patron asked Ms. Laurita to rid the collection of some because of the sexualized way they portrayed women superheroes. So Ms. Laurita showed her that they hadn’t grouped all graphic novels together, but placed each one with books appropriate for readers of the same age.

As a result, she says, “There was no formal challenge; it was a discussion.”

Ms. Dawkins recalls a similar situation when she worked in a high school library in rural North Carolina. A teacher objected to the inclusion of “Boy Meets Boy” in a display of new acquisitions.

“So it became a conversation,” she says. The teacher didn’t see the need for the book because he thought the school had no gay students.

“Oh,” Ms. Dawkins recalls saying, “I went to this high school and I assure you, there were gay students here. They might not have been open about it, but they are now, as alumni.”

The conversation broadened to Ms. Dawkins feeling strongly about having books that spoke to the Muslim and Jewish students, as part of the library’s mission of speaking to and about all students.

According to the ALA, a small percentage of books are challenged by administrators and faculty. But this teacher was not among them.

Nobody called a reporter. Nobody doled out an Intellectual Freedom award.