Fathers helping fathers, so kids can thrive

Loading...

| St. Louis

On alternating weekends, William Howard Lee Jr. gets to bask in the kind of unconditional love and glee that naturally spill out of 5-year-olds. His son Jreisen jumps into his arms, telling him all about his latest adventure or favorite toy.

‚ÄúHe feels like his father can do no wrong, and I love that about seeing the innocence in his eyes,‚ÄĚ Mr. Lee says, his own eyes hidden behind sunglasses as he smiles thinking about his ‚Äúbaby.‚ÄĚ

When Lee enrolled at Fathers’ Support Center (FSC) here in January, he carried burdens that little Jreisen couldn’t see: He grew up without his father, and his stepfather beat his mom before leaving when Lee was 6. Lee was an ex-con struggling to find a better job. He was quick to argue with the mother of Jreisen and Jalon (one of his two 16-year-old sons), and he didn’t see them as often as he wished.

Why We Wrote This

Dads don't always feel valued, especially if they are not living at home. Strengthening their understanding about how to relate to their families is one way to address that.

But he was determined to be a better father than anyone had been to him. ‚ÄúI want to break a generational curse and show my children how to be more productive as a father,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúWe all try to parent the best that we can, but, you know, we don‚Äôt always have the answers, and we don‚Äôt always have the right guidelines to start with.‚ÄĚ

He found some of those parenting insights here, and so much more than he imagined when he first arrived at the no-frills classrooms in this big tan building, shared among social service agencies and nonprofits. It sits on a hill overlooking small brick homes and abandoned lots near a St. Louis highway that hugs a curve in the Mississippi River.

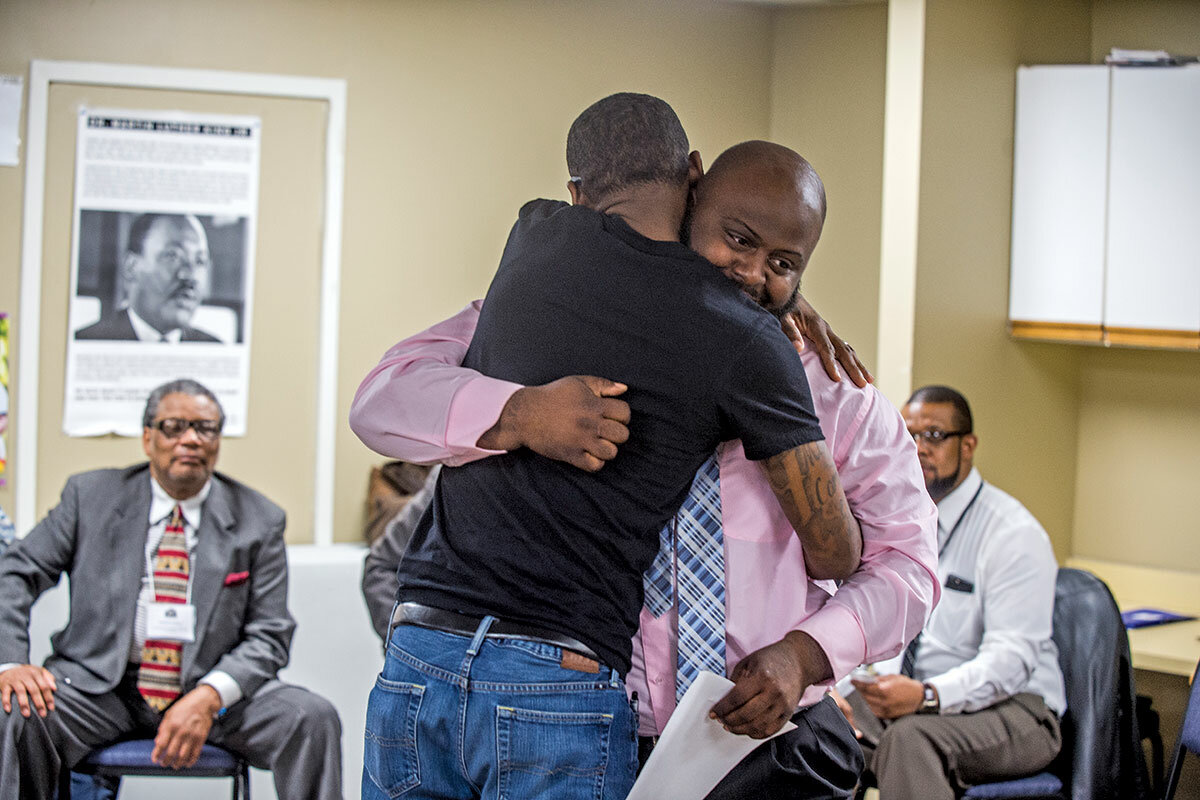

Over the past 21 years, FSC has expanded to four more locations around the city and has given nearly 15,000 low-income fathers everything from job training to relationship skills. Every few months it enrolls a new group for its six-week full-time Family Formation Program, facilitated mainly by other men who have traveled a similar path. Graduates receive a year of follow-up support.

They may come in feeling like a frustrated or failed parent, or even like unappreciated ‚Äúcash registers‚ÄĚ for their kids‚Äô mothers. But they tend to go out feeling more confident as fathers ‚Äď fathers better equipped to play a unique, essential role in their children‚Äôs lives.

***

Nearly 3 out of 10 children in the United States do not live with their biological father, and for African-Americans ‚Äď the majority of FSC participants ‚Äď the figure is closer to 6 in 10.¬†

Regardless of living arrangements, positive involvement by fathers is associated with ‚Äď in academic achievement, social and emotional well-being, and behavior. Yet society is still catching up with how best to nurture those kinds of relationships.¬†

New information is emerging about how places such as FSC affect disadvantaged fathers’ ability to better support their children. And a growing number of communities are starting to reform child-support systems to make room for a broader concept of fatherhood.

‚ÄúPoor dads have totally taken on this narrative of the new father,‚ÄĚ says Kathryn Edin, a sociology and public affairs professor at Princeton University in New Jersey. ‚ÄúThis is who they aspire to be,‚ÄĚ not unlike their higher-income counterparts. But ‚Äúdoing so outside of a strong partner bond or a strong co-parenting bond is very difficult.‚ÄĚ

Too often these fathers are overshadowed by stereotypes of ‚Äúdeadbeat dads‚ÄĚ who callously walk away from responsibilities, adds Dr. Edin, coauthor of ‚ÄúDoing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City.‚Ä̬†

It‚Äôs true that there are men in every social class who abandon their children. But poor men who want to be involved often face steep barriers, from unrealistic child-support orders to ‚Äúmaternal gatekeeping,‚ÄĚ Edin says. Sometimes a mother needs to block access for her or her child‚Äôs safety, but often other reasons prevail, such as the mother moving on to a new partner or not understanding the importance of trying to co-parent.

Supports for dads do have positive effects on their parenting, according to groundbreaking from a study of 5,500 men served by FSC and three other fatherhood programs. One year after participating, the fathers did more age-appropriate activities with their children ‚Äď reading a book out loud or helping with homework, for instance ‚Äď than did the fathers in the randomized control group. They also reported more nurturing behaviors, such as showing patience with their children or encouraging them to talk about their feelings.

Mathematica Policy Research conducted the Parents and Children Together (PACT) evaluation study to gauge the effects of Responsible Fatherhood grants administered by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Some hoped-for results haven’t yet been achieved. The programs overall did not increase the men’s in-person contact with their children, for instance. The men did experience more-stable employment, but that did not translate into higher earnings or larger financial contributions to their kids.

For Halbert Sullivan, founder and chief executive officer of FSC, getting the nonprofit off the ground was tough, but every time he wanted to quit someone would stop by to tell a story about the difference the program was making in people‚Äôs lives. ‚ÄúI am able to see and be a part of the success of families, which leads to success in our community,‚ÄĚ says Mr. Sullivan, sitting in his office, his shelf loaded with fatherhood books and a teddy bear from his grandson.

***

It‚Äôs 8 a.m. on a Wednesday when the ‚Äúwhat‚Äôs up‚ÄĚ session, a daily meeting of fathers in the FSC program, kicks off. The men who join the circle late pay a dollar to the ‚Äúfines‚ÄĚ jar. One by one, the men in the session share something from the day before.

Marcus Jones, who has been up all night with one of his four children, says he‚Äôs learning how to discipline and love them at the same time ‚Äď ‚Äúand tell them what they did right.‚ÄĚ

Scott Couch, father of a 9-year-old girl, says the nutrition class inspired him to make a big bowl of fruit salad for dinner. ‚ÄúThrow mango in it. Good stuff!‚ÄĚ he exclaims.¬†

He‚Äôs hoping he‚Äôll be able to get more access to his daughter, and he‚Äôs showing her that life isn‚Äôt just about buying stuff. ‚ÄúWe all say we want to give them something that we didn‚Äôt have,‚ÄĚ Mr. Couch says. ‚ÄúIt don‚Äôt have to be money.‚ÄĚ For him, it‚Äôs teaching her how to cook.

Sean Buckley, coordinated in purple and gray dress clothes and sneakers, shares quietly that he spoke with someone who ‚Äúhelped me open up in a way I had never opened up to anybody.‚Ä̬†

Father to a 20-year-old and an 8-month-old, Mr. Buckley says his spirits are uplifted by the group. ‚ÄúTo know that you are changing into something for the better, it feels real good.... I didn‚Äôt know I was going to have to stop smoking weed, but I‚Äôm doing it for one simple reason: my child.‚Ä̬†

Affirming nods and smiles pulse around the circle as bonds of trust start to form three weeks into the program. Across the country, men often find the social support networks that are established during such programs crucial to their growth as fathers.

Mentoring shows participants ‚Äúthere are people out there who care for them and who will walk with them as they make this very challenging journey,‚ÄĚ said Brad Lambert, co-founder of Connections to Success, during a webcast discussion last December. His group runs fatherhood programs in Kansas and Missouri and was part of the PACT study.¬†

Lee, who graduated from FSC in February, says that talking about himself was difficult at first. But the daily circles were full of humor and encouragement. ‚ÄúIt was just a brotherhood. You didn‚Äôt see color; you just seein‚Äô another man that‚Äôs going through the same struggles ... and we all trying to find a way to be a positive person.‚ÄĚ

That shared motivation leads to presentations and discussions on topics ranging from domestic violence prevention to positive discipline methods.

***

A printed sheet on the wall of an FSC classroom reads, ‚ÄúNo matter what a man‚Äôs past may have been, his future is spotless.‚ÄĚ

But letting out whatever they‚Äôre holding in from difficult times in the past is part of the process. In today‚Äôs ‚Äúwhat it‚Äôs been like‚ÄĚ session, six participants sit around a large table to talk about growing up with, or without, their dads.

Facilitator Gregory Tumlin shares, first, a harrowing story of abandonment, teen parenthood, homelessness, and finally kicking his addictions and forging a relationship with his children.

‚ÄúI done seen the worst,‚ÄĚ he nearly whispers, his head bowed as the man next to him places a hand on his shoulder. Looking up, he says more firmly, ‚ÄúI get frustrated when I see some men who think being a father is a game.‚ÄĚ

Some of the men here had father figures step in to give them help, but they never completely filled the void.

‚ÄúMy cousin‚Äôs father used to come pick him up all the time, and that‚Äôs something that used to touch me, man,‚ÄĚ Buckley says. He wipes his eyes with a paper towel, sniffs, and pauses. ‚ÄúCan you throw me in the air like that?‚ÄĚ he remembers thinking.

Looking back, he appreciates uncles who taught him and his cousins a skill, such as how to hang drywall, even though the discipline they imparted sometimes came at the crack of a belt.

Of the three men here who did grow up with their dads, two faced abuse and the third got involved in neighborhood gang activity.

Couch doesn‚Äôt shy away from describing extreme physical and emotional abuse, which his sister didn‚Äôt experience or even know about. As a ‚Äúwhite kid in the ghetto,‚ÄĚ he says, he‚Äôd run down the alley and get beat up, but he was more afraid of what awaited him at home.

His voice loud and raw, he chronicles his complex emotions about his alcoholic father, who has since died, including that he offered some useful lessons despite it all. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm never mean to women, never missed a day of work,‚ÄĚ Couch says.

With many of the participants, the first step in being a better father is to not follow some of the ways they were raised. ‚ÄúA lot of us tried to parent the way that we were parented,‚ÄĚ says Lawrence Simmons Jr., a graduate of the program here and now a facilitator. ‚ÄúIf you know it had a negative effect on you, then we have to find an alternative way of doing it.‚ÄĚ

***

American families are far more complex today than they were in the days of Ozzie and Harriet. Four out of 10 children are now born outside marriage. By their fifth birthday, 78 percent of those children have seen their parents split up or change partners, have gained a new half-sibling, or both, Edin and her coauthors in Issues in Science and Technology.

As a result, society needs to ‚Äúfundamentally shift toward seeing co-parenting as a key social role,‚ÄĚ she says.

Moving in that direction, FSC, the Center for Urban Families in Baltimore, and some other fatherhood centers have added programs for mothers and co-parenting pairs in recent years.

As a young teen, Lee made only brief contact with his father, ‚Äúand we kind of went our separate ways from there,‚ÄĚ he says, wearing a black jacket and shiny stud earrings, his black baseball cap removed in lingering obedience to the rules here. His mother raised him to be respectful and nurturing, he says, ‚Äúbut I was missing something.‚ÄĚ

Just before Father‚Äôs Day in 2011, after serving 10 years in prison, Lee reached out to his father, who welcomed the overture. ‚ÄúNow we have one of the best relationships ever,‚ÄĚ he says. What it took, he notes, was ‚Äúfor me to forgive him.‚Ä̬†

He realized during his time at FSC that he needed to seek such forgiveness from Yolanda Cole, the mother of Jalon and Jreisen. (He also hopes to improve things with the mother of William, his other teen, but she’s recently avoided his attempts to make contact.) Communication between Lee and Ms. Cole had long been stymied by arguments.

Lee says the program has taught him how to listen better. ‚ÄúI didn‚Äôt give her enough credit for the things she was saying because I really wasn‚Äôt fully hearing her,‚ÄĚ he says.

FSC‚Äôs program delivers about 10 hours of . When needed, family therapists work with the men ‚Äď and the women, if they‚Äôre willing. Out of the four programs in the PACT study, it was the only one to show improvements on interactions with the mothers.

During one unusual session, the men talk with a panel of women volunteers. ‚ÄúThen they realize ... ‚ÄėWell, I‚Äôve been judging her, but this is how women actually feel,‚ÄĚ Mr. Simmons says with a chuckle. ‚ÄúSomeone has to humble themselves so they can actually have a productive conversation.‚ÄĚ

Simmons is one who has reestablished a healthy relationship with the mother of his three children. A 2015 graduate of the program, he reunited with her nearly 31 years after their split.

When they announced they‚Äôd be having a civil ceremony in 2017, he says, his 30-something daughter told him, ‚Äú ‚ÄėNah, you ain‚Äôt going to a courthouse. You‚Äôre going to marry my mother the right way!‚Äô ‚ÄĚ

***

During a symposium on child support for each FSC group, the men can bring in paperwork and get legal assistance to lower their payments if they qualify.

But the overarching message is that ‚Äúchild support is not the enemy,‚ÄĚ Simmons says. Some of the fathers are reminded that if they were caring for a child full time, they would likely be paying far more in support than they are now.

Yet the flip side is also true: Experts such as Edin say those who run child-support agencies need to get the message that fathers are not the enemy, either. Some states take as much as 65 percent of men‚Äôs income if they get behind, and adjustments are hard to come by even when a man loses his job. Noncustodial fathers are more likely to pay child support ‚Äď and stay involved ‚Äď if the amount remains below 35 percent of income, Edin says, or if they are allowed to make informal contributions of goods and services, such as doing household jobs. That‚Äôs an innovation some states have been trying.¬†

When Lee wanted more formal visitation with Jalon about a year ago, he called the child-support office and said he was considering volunteering to pay. The woman on the phone laughed at him, he says, and asked him why he‚Äôd want to do that. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs like child support is not really even geared to actually helping the child,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs so sad.‚ÄĚ

Currently he pays support for both 16-year-olds and hopes he will be able to contribute for Jreisen soon, too. He now has a job washing dishes ‚Äď humbling for a man whose teenage son does the same thing ‚Äď but the center helped him get certification to drive a forklift and a commercial driver‚Äôs license, which he expects will lead to better work. His ultimate goal is to start a business and hire other formerly incarcerated people.¬†

Lee says he‚Äôs excited about ‚Äúactually being able to stand on my own two feet and actually help my children financially.‚Ä̬†

‚ÄúI can actually be there,‚ÄĚ he notes, ‚Äúand we can do things together, and I don‚Äôt have to worry about if I got the money to pay for it if my son hungry.‚ÄĚ

***

A week before his group’s graduation in February, Lee visited Cole at a tax office where she works. Looking for a fresh start, he took the new communication and fathering skills he’d learned at FSC and approached her with fresh hope. She remembers the emotional day well.

‚ÄúHe apologized for a lot of the things that went on between us and the kids,‚ÄĚ she says on a rainy afternoon, her purple fingernails resting on the kitchen table. The cream-colored brick home she shares with Jalon and Jreisen sits on a quiet street in Granite City, Ill., across the river just north of St. Louis.¬†

Before attending the program, she says, Lee would let a few months go by before reaching out to the children, and would come down on Jalon for not taking the initiative to see him. She tried to tell him that you can’t push things on teenagers but have to befriend them and support their interests, which for Jalon includes running an e-commerce business after school.

The better communication with Lee has been ‚Äúa big relief,‚ÄĚ she says. For so long, she‚Äôs had to act as both mother and father, although the boys have had positive interactions with another man, the primary parent to her 11-year-old son. She frequently reminds Jalon, who‚Äôs protective of Jreisen, that he doesn‚Äôt have to take on the father role.¬†

Jalon, perched quietly on a kitchen stool, says he‚Äôs noticed the change in his dad. ‚ÄúHe‚Äôs more caring, more open arms,‚ÄĚ he says, and when he talks to Mom, ‚Äúit‚Äôs not yelling but actual conversation.‚Ä̬†

When Lee offered an apology, ‚ÄúI was able to forgive him,‚ÄĚ Jalon says.

Cole tears up momentarily as she talks about the new dynamic. ‚ÄúAll I really wanted was for him to be a good dad to his kids. And he‚Äôs making forth the effort.‚ÄĚ

For Lee, the payoff with his sons has been immediate, and recently included taking them to the Saint Louis Science Center, where they laughed in a wind chamber and climbed into the driver‚Äôs seat of a giant farm combine. ‚ÄúI can tell from his actions that he likes the fact that I‚Äôm trying,‚ÄĚ Lee says of Jalon. ‚ÄúI can see it and I can hear it in his voice. If I tell him now I love him, he‚Äôll sound excited when he say it back.‚ÄĚ