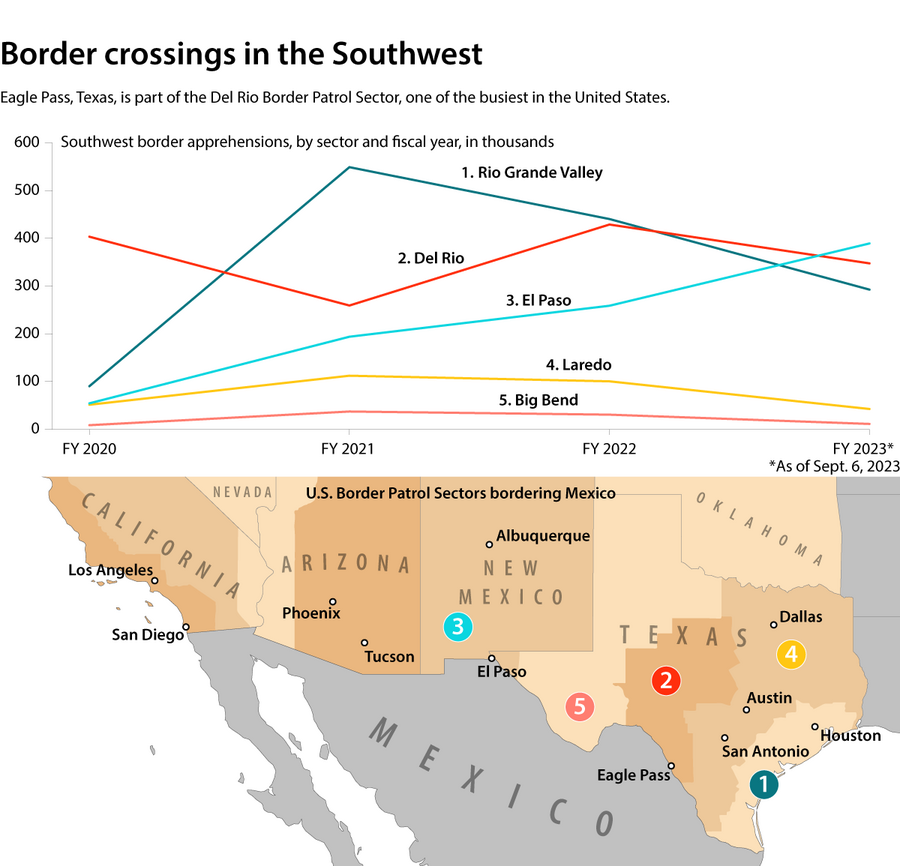

Residents of Eagle Pass, Texas, live with the border crisis in ways most of the rest of the U.S. does not. They want a secure border. They also want humane treatment of migrants.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

Sara Miller Llana

Sara Miller Llana

Sometimes, the most challenging thing about a story can be just getting there. That’s been the case here in Bangladesh, where photographer Melanie Stetson Freeman and I are on the last leg of a global project about youth facing climate change.

It started months ago with the visa – which I wasn’t sure I’d get despite countless phone calls, emails, and trips to the consulate. It came five days before our planned departure. Then there was the matter of getting to the capital, Dhaka. Sudden storms meant aborting our approach minutes before landing and instead heading to Kolkata. That led to six drama-filled hours on a runway, as India would not let us off the airplane (because of the Pakistanis on the flight), and we couldn’t take off again until we got approval from Boeing itself. (There was more, but I’ll spare you.)

Once in Dhaka, “getting there” meant going slowly. Very slowly. At all hours, going just a few miles took hours amid a cacophonous, color-splashed, belching wall of traffic. Outside Dhaka, “getting there” got scarier. Much scarier. Cars, trucks, passenger buses – the most terrifying of all – rickshaws, bicycles, dogs, goats, and people share highways where the only rule seems to be “never yield.”

Yet commuting can also be a joy. I’m writing this on a passenger ferry crossing the wide Padma River, where vendors are hawking puffed rice served with chiles, cucumbers, and lime. Everyone asks where we’re from and takes a selfie with us. In a country with more than 700 rivers, we’ve taken every manner of water vessel. The journey we’ve had to take most frequently: crossing the Pusur channel while keeping our balance on a tiny, standing-room-only boat.

They are the anecdotes and adventures that almost never make it into published articles. But for journalists, “getting there” can sometimes be what we remember most.