This is a big week for Donald Trump. But it could be even bigger for what he represents. Mr. Trump kindled an unprecedented modern rebellion against Washington. But facing a full docket of inside-the-Beltway politics, can Trump keep that populism alive? Staff writer Linda Feldmann suggests today’s populist spirit is bigger than any one man – even Donald Trump.

Why is ���Ǵ��� Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usAlready a subscriber? Log in

Already have a subscription? Activate it

Ready for constructive world news?

Join the Monitor community.

Subscribe Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The establishment is breathing an enormous sigh of relief in France today. Centrist Emmanuel Macron will face far-right candidate Marine Le Pen in the May 7 presidential election. The relief is that Ms. Le Pen wasn’t joined by the far-left candidate, who was also polling well before Sunday’s first round of voting.

But there’s a danger in that kind of relief. Is Mr. Macron’s primary value that he’s not someone else? Later this week, we’ll take a look at why Macron’s supporters like him. And that’s important. What’s needed is not a defeat of the so-called extremists. What’s needed is a positive and compelling vision for a future that embraces all – including those feeling left behind by globalization. If relief only leads to complacency, then any victory will prove a hollow one.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

( 13 min. read )

Does Marine Le Pen even matter any more? It's always been easy to dismiss the French presidential candidate as a fringe politician. Now, early polls suggest she'll finish a distant second on May 7. But why has she made the far-right more popular than any time in recent memory? That's the real story of Ms. Le Pen, and perhaps of the election, too, staff writer Sara Miller Llana writes.

( 5 min. read )

The integrity of the death penalty in the United States is facing its biggest challenge in generations. As death-penalty drugs become scarcer, states are trying to draw a curtain around the event. At the same time, staff writer Patrik Jonsson reports, fewer people are willing to be witnesses – worried what they might see.

Overlooked

( 5 min. read )

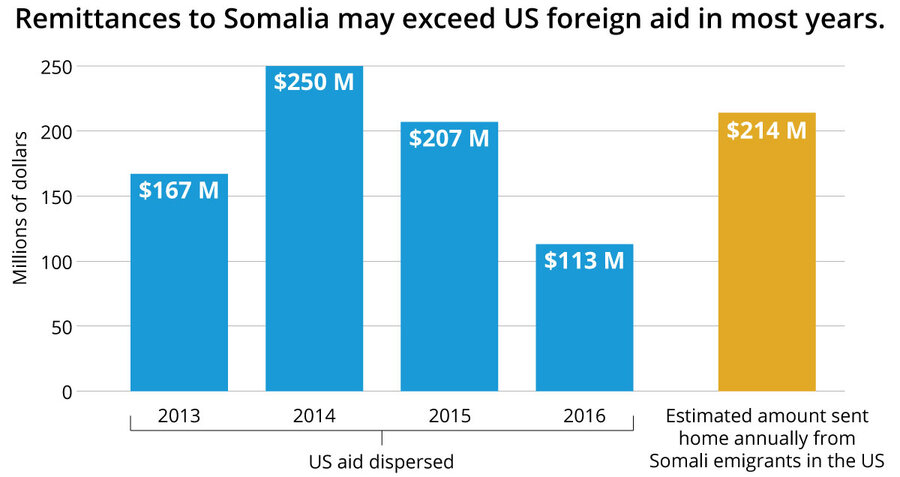

Compassion, it seems, can be an economy. Just look at Somalia, where the biggest form of aid is other Somalis worldwide.

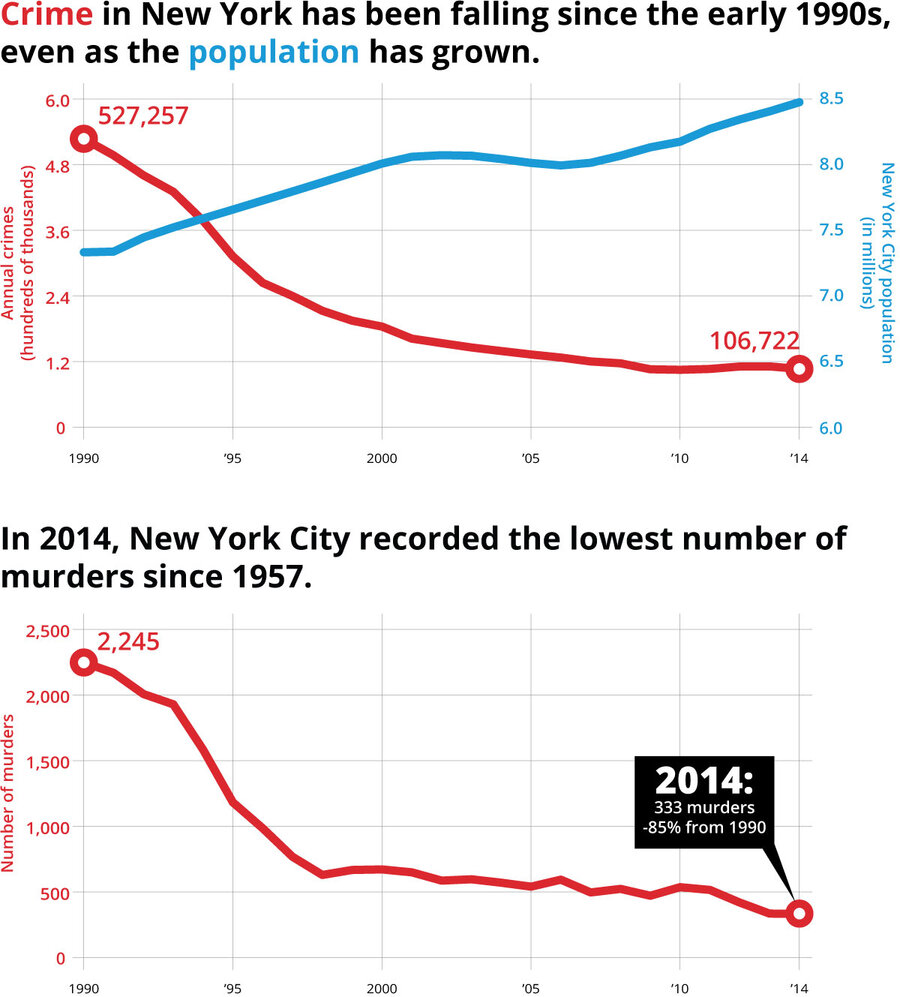

The real story on New York City and crime

Fighting crime is often presented as an either/or proposition: Either be tough or you've gone soft. But New York City suggests that kind of thinking is not only an oversimplification – it can also miss the good that takes root.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

At the heart of many Middle East conflicts lies a fierce rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The two compete for influence as countries, as oil giants, and, most of all, as self-proclaimed guardians of Islam. Yet over the past year, each has also entered a new kind of rivalry, one that is peaceful, perhaps even healthy in possibly setting a model. Both now have leaders eager to win over young people with fundamental reform.

For Saudis, that leader is Mohammed bin Salman, the deputy crown prince who is barely over 30. He wields much of the power in the ruling monarchy and last year set out a strategy called “Vision 2030.” Among other reforms, the plan calls for a more open society and big investments in a non-oil economy that emphasizes innovation, mining, and tourism (such as building a Six Flags theme park and perhaps a “museum of ice cream”).

For Iranians, the leader is President Hassan Rouhani, elected as a reformer in 2013 and now competing to be reelected in a May 19 election that is tightly controlled by the ruling Muslim clerics. He has slightly improved the economy and struck a nuclear deal with the West that weakens sanctions on Iran. In December, he issued a “Charter of Citizens’ Rights” that emphasizes freedom of speech and assembly, a right to access information, and a clean environment. In a speech last month, Mr. Rouhani said, “Are not the people the owners of this country? Shouldn’t the people be supervising the government...?”

In both Iran and Saudi Arabia, more than 60 percent of the population is under 30 years old. This youth bulge is restless from high unemployment and a widening exposure to foreign culture. Young people are eager to challenge traditional authority and even interpret religion in their own way. As historian and journalist Christopher de Bellaigue writes in a new book, “The Islamic Enlightenment: The Modern Struggle Between Faith and Reason,” ideas about the value of the individual, rule of law, and representative government “are now authentic features of Islamic thought and society.”

Both Rouhani and Mohammed bin Salman are struggling against religious conservatives, who remain powerful either in government or in society. In Saudi Arabia, however, clerics who once monitored social behavior have been mostly subdued. Young people are being given access to live music concerts, some with female performers. In February, the country sponsored Comic-Con, a three-day festival about fictional heroes that saw a mixing of young men and women.

In his speech, Rouhani said the government has no “legitimate meaning” unless the people are “satisfied” with their leaders. “All people, regardless of their sex, religion, tribe, or political thought must be equal before the courts and the law, and have the same rights,” he said. Such words are a far cry from the current doctrine of an unelected Muslim ayatollah as supreme leader.

Since 2014, as world oil prices have fallen and Iran suffered from sanctions, each country has had to cut spending yet also appease a rising cohort of youth. Iran saw massive protests in 2009 over election fraud while Saudis saw some unrest during the 2011 Arab Spring. Reformist leaders are now more popular. And among each country’s hardline factions, they are more tolerated in hopes of fending off unrest.

Most of all, young people are watching the reform efforts in each other’s country. Whichever country begins to make the reform ideas real – and that is still uncertain – can claim a new kind of leadership of ideas among Muslims. Perhaps that will then lessen their rivalry with weapons in Middle East conflicts.

A ���Ǵ��� Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 2 min. read )

Most of us have experienced, at one time or another, a sense of sorrow or mental darkness. For so many, the Bible is a source of comfort in such times, promising the continuity of God’s goodness. In the Gospels, we learn how Christ Jesus proved that an understanding of God’s goodness not only comforts, but also heals. Diving into the Scriptures, and reasoning spiritually, a writer discovered for herself how grief can be healed by understanding God as good. Whether struggling with sadness, sorrow, or any other sense of gloom, learning more about God’s love can wipe it away and restore a sense of joy.

A message of love

A look ahead

Thank you for reading today. We’re moving now into producing these story packages daily, with the aims of getting at some of the deeper questions in the news and of turning up some fresh perspectives. Please let us know how we’re doing.