The Voting Rights Act hangs in the balance. Remember those who lost their lives for it.

Loading...

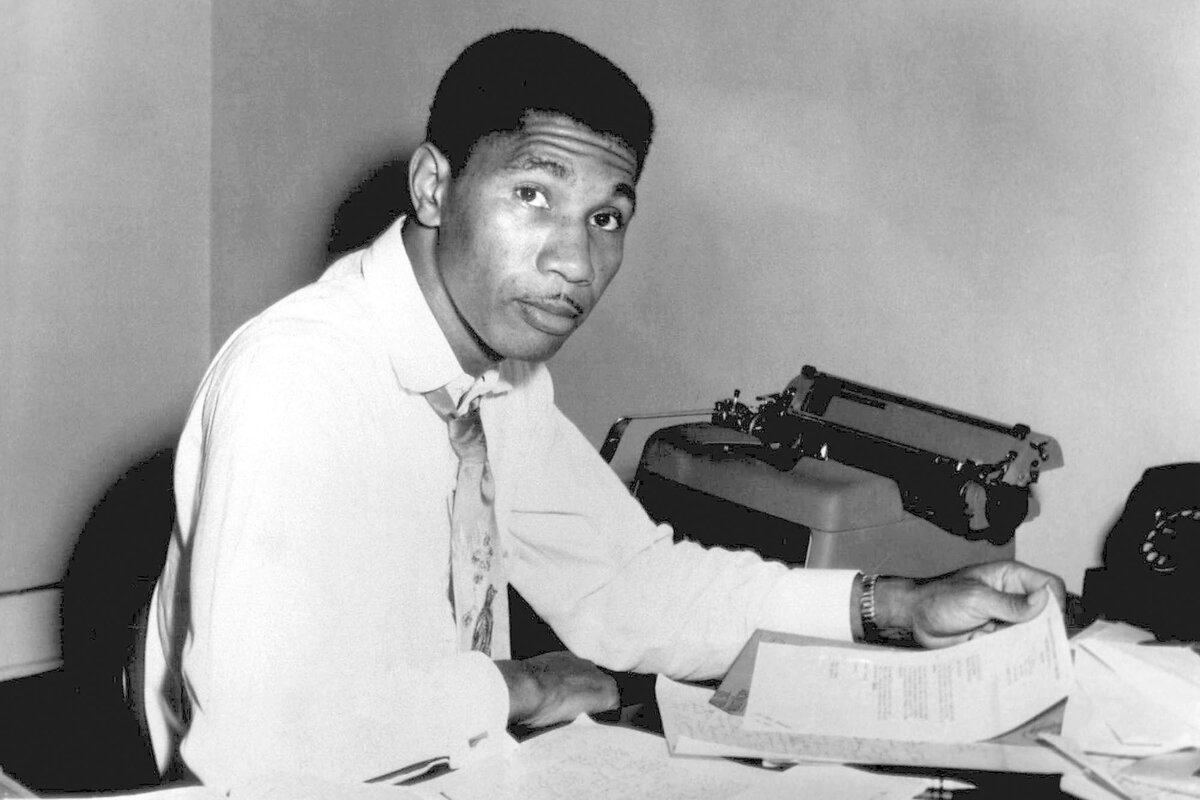

Medgar Evers was 37. The NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi was grasping a handful of shirts that said “Jim Crow Must Go” when he was in 1963.

Maceo Snipes was also 37. When the World War II veteran cast his vote in the Georgia Democratic primary on July 17, 1946, he was the only Black man in Taylor County to do so.

One day later, he was .

Why We Wrote This

The context of why civil rights activists like Medgar Evers and Maceo Snipes were murdered has been lost in the current conversation about the Voting Rights Act at the Supreme Court.

Last week, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments on a Louisiana redistricting case asking whether using race as a factor in congressional voting maps is unconstitutional. The Trump administration and the state of Louisiana contend that using race to draw the maps is discriminatory in and of itself. Considering the lives of Mr. Evers, Mr. Snipes, and others who died in the name of civil rights and voting rights, the irony is loud.

Albeit, not as loud as a gunshot.

It is unfathomable that the context of why those civil rights activists were murdered has been lost in the current conversation about the Voting Rights Act. The “race-based” elements designed to protect marginalized voters did not appear from thin air. They are the fading vanguard standing against generational violence and voter intimidation.

In another twist, it was one of the founders of the Republican Party who authored a bill in the name of civil rights. Charles Sumner, a former U.S. senator and abolitionist lawyer from Massachusetts, crafted principled legislation to protect Black people from discrimination in public transportation and other venues. While it fell short of protecting African Americans in economic and social life, Sumner’s posthumous bill became the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

The following year, an ideological rebuke of Sumner’s policy violently progressed through the South. In an effort to intimidate Black voters and eliminate the gains of Radical Republicans during Reconstruction, the Hamburg Massacre kicked off a series of white mob violence that ultimately reinstalled legal segregation and the fascism of Jim Crow. In 1883, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was deemed “unconstitutional” by the Supreme Court during the Civil Rights cases.

Jim Crow rule lasted for almost a century, until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act were passed – not that legislation prevented political and social brutality. Martin Luther King Jr., another champion for civil and voting rights, was assassinated in 1968. In the decades to come, Southern strategists such as Lee Atwater and Republican-led entities would continue to chip away at seemingly impenetrable voting rights legislation by manufacturing “culture wars” designed to focus resentment on progressive gains.

Even as statues to the likes of Rep. John Lewis have been raised in Georgia and the legacy of “Bloody Sunday” is still common knowledge, that history has not translated into the conscience that preserves and strengthens voting rights for all Americans. That collective failure presented itself during the Obama administration in 2013, when Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act took a big hit from the Supreme Court in the name of “preclearance.”

In short, the section was an acknowledgment of the dark recesses of American history – of those pockets and municipalities where it was a death sentence to vote. “Prior to 2013, Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act required states and localities with an extensive history of racially discriminatory voting practices to submit any changes in their election laws and policies or electoral district maps to the federal government for advance review before putting them into effect,” writes the .

In the Shelby County v. Holder decision, a majority of Supreme Court justices ruled that the formula used to determine which states and sites were under preclearance was no longer needed. “The Voting Rights Act of 1965 employed extraordinary measures to address an extraordinary problem,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority, ”an insidious and pervasive evil which had been perpetuated in certain parts of our country through unremitting and ingenious defiance of the Constitution.” Then Chief Justice Roberts wrote that those measures were no longer necessary in today’s South.

The ruling can be seen as an allegory for how much our collective conscience has flinched away from regarding the horrors of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Supreme Court didn’t throw out Section 5 entirely. But modern efforts to restore preclearance standards, such as the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, haven’t passed. The House passed the Lewis Act in 2021, but it fell short of the 60 votes needed in the Senate.

Now, Section 2 hangs in the balance at the high court. While it’s unlikely that the entire section will be deemed unconstitutional, it’s likely that the protections against gerrymandering and mapmaking that dilute Black voting power will be dissolved. It’s a reminder that politics extend beyond the voting booth, but impact every aspect of our lives.

“What then does the Negro want?” Mr. Evers asked in a May 20, 1963, speech on Mississippi radio. “He wants to get rid of racial segregation in Mississippi life. ... The Negro citizen wants to register and vote without special handicaps imposed on him alone.”