Joseph Ellis talks about 'The Quartet' and the four perceptive men who shaped a reluctant nation

Loading...

Just about everything Joseph Ellis needs can be found in late 18th-century America. Or, rather, the former colonies that led to the creation of the United States of America.

EllisŌĆÖs r├®sum├® includes biographies of founders and presidents George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Another book explores the relationship of John and Abigail Adams.

Then, too, there are his broader sketches of a larger cast of statesmen (hello, Ben Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and so on) who pushed for the Declaration of Independence and the Revolutionary War. In these books, ŌĆ£Founding BrothersŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Revolutionary Summer,ŌĆØ Ellis examines the daring and perilous notion of even attempting to break away from England.

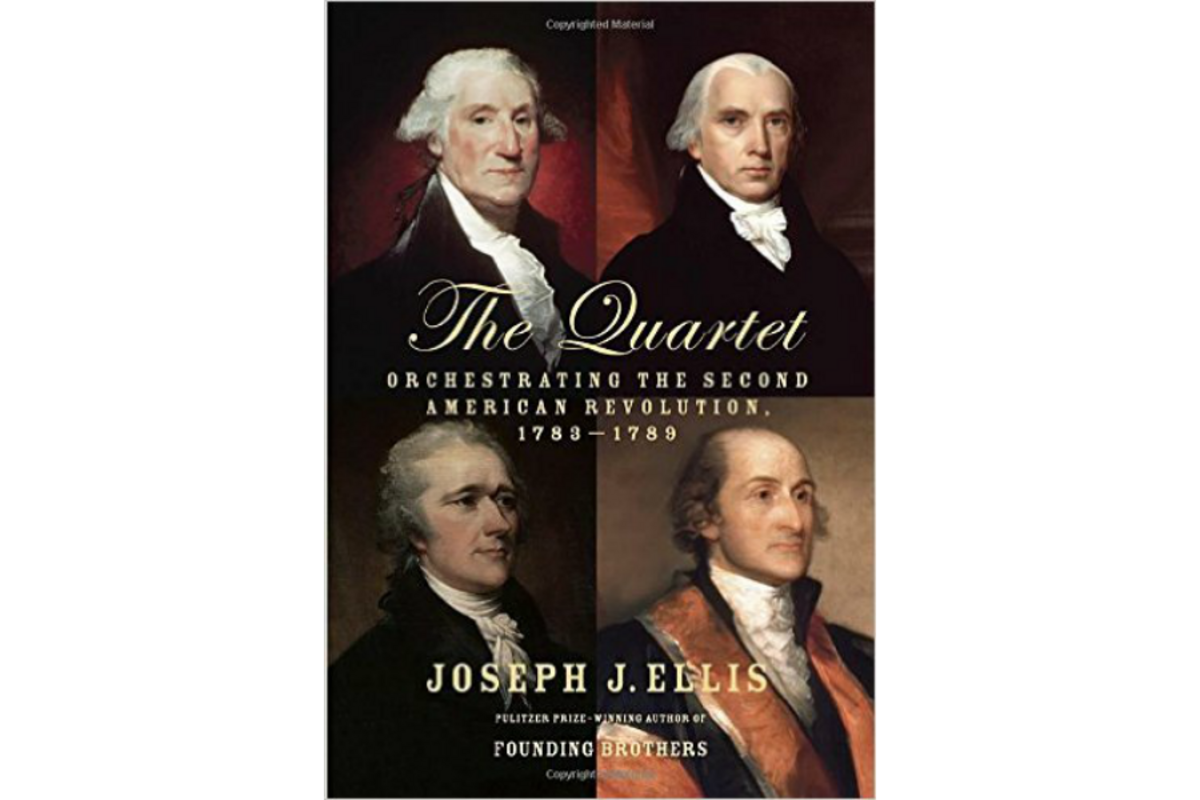

Now, in the month that America celebrates its 239th birthday, Ellis is telling another important story from the Revolutionary Era. In The Quartet (290 pages, Knopf, $27.95), he details the dramatic uncertainty of converting military victory over the British into a united and independent nation.

Concentrating on the years 1783 through 1789, Ellis offers a vivid, nuanced portrait of an overlooked part of our history. Many Americans, this one included, tend to think of Jefferson writing the Declaration of Independence, then a war that included struggles at Concord and Valley Forge and, finally, the French helping run off the British. From there, itŌĆÖs on to a quickly adopted constitution, the Civil War, a couple of World Wars, Civil Rights, Watergate and on to iPhones, Uber, Caitlyn Jenner and Deflategate.

Or something like that. Ellis delves into the disparate views and political debates engulfing the future United States following the British surrender. His quartet ŌĆō George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison ŌĆō combined willpower, political savvy, and resilience to overcome a prevailing sentiment that any kind of national government would represent another form of tyranny and oppression.

What seems so obvious, that the radical colonists who broke from England would abhor the idea of being tethered to another form of centralized political power, is, in mainstream popular history, an idea that is rarely explored. Or, as Ellis puts it, ŌĆ£the very term American Revolution implies a national ethos that in fact did not exist in the population at large.ŌĆØ

Drawing on an expanding collection of letters and documents, Ellis backs up his assertion ŌĆ£that by 1787 the confederation [of states] was on the verge of dissolution.ŌĆØ

In 1781, the 13 ŌĆ£sovereign states that were nations themselvesŌĆØ formed a confederation, a loose alliance that afforded little national authority of any kind. During and after the Revolutionary War, the perpetually underfunded confederation sank deeper into debt. Washington and Hamilton struggled to feed, clothe and arm their ragtag soldiers. After the war, veterans received no pensions for their service.

Ellis, again and again, puts contemporary readers in the mindset of the period. People then lived out their lives in a 30-mile radius and often viewed anyplace else with suspicion.

They lived, he writes, ŌĆ£in a premodern world that is forever lost to us. That world was pre-democratic, pre-Darwin, pre-Freud, pre-Einstein, pre-Keynes, and pre-Martin Luther King Jr.ŌĆØ

Congress, when it bothered to convene, was not designed to carry out national domestic and foreign policy to any significant degree. Quorums occurred on an occasional, haphazard basis. Were it not for WashingtonŌĆÖs ingrained, unspoken belief in a military subservient to civilian rule, the independent states could easily have been subjected to a martial government.

Ellis notes ŌĆ£the transition from the Declaration of Independence to the Constitution cannot be described as natural.ŌĆØ And, he writes, without WashingtonŌĆÖs appearance at the 1787 convention, hardly a sure thing, even the conversation would have stalled. Madison played the most prominent role in the creation of the Constitution, but without the nationalist backing and vision of Jay and Hamilton, the Constitution and Bill of Rights could not have been completed and approved.

In several instances, Ellis reminds his readers of the importance of re-examining what these now-sacred founding documents werenŌĆÖt intended to be. Madison viewed the Bill of Rights as an add-on to placate critics, not a philosophical document to be preserved for eternity. So, too, with the Constitution, the foundation of our democracy, but not, in the minds of its supporters, an unwavering document never or rarely amended.

Ellis makes special mention of the controversial right-to-bear-arms Second Amendment.

ŌĆ£It is clear that MadisonŌĆÖs intention in drafting his proposed amendment was to assure those skeptical souls that the defense of the United States would depend on state militias rather than a professional, federal army,ŌĆØ Ellis writes. ŌĆ£In MadisonŌĆÖs formulation, the right to bear arms was not inherent, but derivative, depending on service in the militia. The recent Supreme Court decision [in 2008] that found the right to bear arms an inherent and nearly unlimited right is clearly at odds with MadisonŌĆÖs original intentions.ŌĆØ

Ellis, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for ŌĆ£Founding BrothersŌĆØ and the National Book Award for his Jefferson biography, spoke to The Monitor about the struggle to make the states united and other Revolutionary matters during a recent interview. Following are excerpts from that conversation.

On his interest in writing about another historical period: IŌĆÖve thought about moving off into the 20th century on occasion. I started to do a book on George Kennan, the great statesman [and diplomat]. But it got co-opted by somebody who had done the authorized biography.

But in moments of doubt I refer back to that great figure in American history, the bank robber Willie Sutton, who back in the '50s was this lovable guy who kept robbing banks and getting caught and getting thrown in the hoosegow. They asked Willie why he kept robbing banks and he said, ŌĆ£Because thatŌĆÖs where they keep the money.ŌĆØ (Sutton himself later wrote that he never said those words but the phrase has long been credited to him anyway.)

And the late 18th century is sort of the Big Bang in American history, the moment when the values and institutions that still abide in the oldest enduring republic in modern history were all created and so there is a sense that you can never know too much about it. History is an accumulative discipline ŌĆō historians are like symphony conductors, they get better with age. Part of thatŌĆÖs because it requires a reservoir of knowledge and a level of distillation and digestion. And the papers on these prominent figures have been coming out now for 50 years and theyŌĆÖre reaching, in many cases, the end.

This happens at a time when the historical profession is moseying on down other trails, looking for the neglected or the voiceless women, Native Americans, African-Americans, so at the very moment we can now know more about the most prominent of the so-called founders, most professional historians are not looking there. IŌĆÖm one of the few card-carrying historians thatŌĆÖs written a lot about this.

On the origins of the book: The seeds were planted when I was asked to judge an oratorical contest at a middle school for dyslexic boys in Putney, Vt., because my son was teaching there. I was forced to listen to 28 young boys try to recite the Gettysburg Address. At some point in the process, I realized that the first clause in the first sentence of what is arguably the greatest speech in American history is historically incorrect. ŌĆ£Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation.ŌĆ”ŌĆØ Well, no, they didnŌĆÖt. They brought forth a collection of sovereign states that rebelled from England as sovereign states and then they went their separate ways after the Revolution under the Articles of Confederation. So, if you begin with the assumption that Lincoln is making, that we are a nation that comes together to declare independence, then itŌĆÖs no great transition to 10 or 11 years later when we come together to declare our nationhood. But thatŌĆÖs not true. ThatŌĆÖs not the way it happened.

I think, for the vast majority of Americans, they donŌĆÖt think about this at all. For those that are even historically literate, though, this period from the Declaration to the Constitution is a kind of dead zone. And so a recognition that thereŌĆÖs a different story that needs to be told was the inspiration to try to tell it. Most historians arenŌĆÖt looking for this ŌĆō again, theyŌĆÖre interested in other topics and IŌĆÖm not begrudging them that at all. I think what theyŌĆÖre writing in some cases is quite valuable but, as a teacher in a liberal-arts college, IŌĆÖm forced to teach the mainstream story because these kids donŌĆÖt know it. I realized this story isnŌĆÖt known.

It doesnŌĆÖt fit what we want to believe. In a democracy, what we want to see is major changes effected from the bottom up. That is at least partially true for the Revolution itself, for the war. Mobs did form, this was a popular movement. There was also about 20 percent of the population that were royalists, another 30 percent that wished the whole thing would just go away.

But the move from independence to nationhood, there were no mobs forming to do this, nobody wanted this. It was not popular because most people didnŌĆÖt have horizons that went beyond the fences of their farms or the borders of their towns. Plus, the whole rationale for rebelling from the British was to escape some far-away government that didnŌĆÖt have your own interest in mind. And the creation of a federal government looked eerily similar to the very kind of parliamentary government that we were escaping from. So the only way this could have happened was from the top down.

Unless you think the creation of the Constitution and the formation of a sovereign American nation was a mistake ŌĆō believe it or not, there are some people that think that ŌĆō then this is a major event that needs to be understood in ways that thus far it hasnŌĆÖt. This leads me to the quartet as four people who were instrumental in instigating and then collaborating to orchestrate both the coming of the convention, the convention itself, ratification and then, in MadisonŌĆÖs case, single-handedly writing the Bill of Rights. They didnŌĆÖt do it alone. There were 55 people at the convention in Philadelphia and there are 1,646 in the various ratification conventions, but these are the people that led it and oversaw it.

On how the quartet led the way: I donŌĆÖt want to be misunderstood to in any way suggest these people were divinely inspired, that tongues of fire appeared over their respective heads at any time. Or that they had some unique access to heavenly wisdom. No, they were all men, flawed in all the ways that men are flawed, but in this particular moment, they came together and made something happen that was otherwise never going to happen.

If they hadnŌĆÖt done that, we wouldnŌĆÖt be the United States of America. Playing out the alternative scenarios is a game that nobody can claim is a science, but I think we would have seen the Europeanization of the North American continent. That is, we would be like a big EU if we had stayed together. More than likely, the Civil War would have happened earlier, the South would have been a separate confederation, probably would have signed an alliance with Britain because Britain needed its cotton, all these are highly speculative. But the United States wouldnŌĆÖt be the major power in the world that it is.

On the Tea Party sentiment through American history: In 1787, the anti-federalists, who oppose the Constitution and oppose it on the grounds that it repudiates the principles of 1776, what theyŌĆÖre saying is, ŌĆ£Even though I voted people into this government, I donŌĆÖt think they really represent me because the government is too far away.ŌĆØ Patrick Henry, in the ratification of the commonwealth of Virginia, said, well, suppose a law of tax is passed by this new government and all the representatives from Virginia voted against it, then weŌĆÖre being taxed without our consent.

Now, you see, thatŌĆÖs what people down in Texas think about the Affordable Care Act. ThatŌĆÖs the real origin of the Tea Party. The real origin of the Tea Party isnŌĆÖt the Boston Tea Party, itŌĆÖs the anti-federalists, who basically are saying, ŌĆ£Even though you think weŌĆÖre represented and claim that, we still think of government as them, not us.ŌĆØ This can assume paranoid proportions, back then and now. ThatŌĆÖs a longstanding tradition. ItŌĆÖs not a terribly noble tradition because this is the same group that makes the argument that they had to protect slavery because of the statesŌĆÖ rights argument, the same argument in regard to desegregation.

On slavery being ignored at the Constitutional Convention: The neo-abolitionists of today who look back ŌĆō one thing youŌĆÖve got to remember, abolitionists in the 19th century said, ŌĆ£Let the South go in peace. We donŌĆÖt want war.ŌĆØ ThatŌĆÖs what would have happened if they would have forced the issue in Philadelphia in 1787: The South would have seceded then.

The founding generation faced an impossible choice. Do you want to create a new national government or do you wish to make a moral statement about slavery? And you canŌĆÖt do both. ItŌĆÖs an intractable problem.

ItŌĆÖs a tragedy. Is it a Greek tragedy or a Shakespearean tragedy? A Greek tragedy means itŌĆÖs built-in, itŌĆÖs inevitable. A Shakespearean tragedy means that human behavior or agency could have changed it. I donŌĆÖt see how they could have done it. If you think they (could have), you have an obligation to explain how they could have put slavery on the road to extinction. Most of the people in Philadelphia (at the convention) thought slavery was going to die a natural death. If they could contain it in the Deep South, it would just die because slave labor could not compete on equal terms with free labor.

So we can isolate it and it will die. They didnŌĆÖt foresee the cotton gin and the cotton kingdom. Adams thought that, Jefferson thought that, although JeffersonŌĆÖs really going to fail the test on this. They didnŌĆÖt know what was going to happen in the first half of the 19th century. They saw it moving in a different way.