'Print is Here to Stay': a WSJ article spreads like wildfire

Loading...

It’s no wonder a recent Wall Street Journal essay on the longevity of print books is circulating the web faster than “Fifty Shades” climbed bestseller lists.

It is, after all, music to many bibliophiles’ ears.

In “,” writer Nicholas Carr argues just that and makes a convincing case that digital books will complement, not replace, traditional print books.

“Lovers of ink and paper, take heart,” Carr begins. “Reports of the death of the printed book may be exaggerated.” Despite the initial prognoses about publishing going all digital by 2015, digital may very well be a supporting, not starring, actor in years to come, says Carr.

“It may be that e-books, rather than replacing printed books, will ultimately serve a role more like that of audio books – a complement to traditional reading, not a substitute,” he writes.

He outlines the evidence: A recent Pew Research Center poll revealed that 89 percent of readers said they had read at least one printed book during the preceding 12 months. By comparison, only 30 percent reported reading even one e-book in the same period.

What’s more, after “the initial e-book explosion,” the growth rate for e-book sales is slowing from triple-digits to about 34 percent in 2012, suggesting that initial spike in growth was an aberration, a reflection of the technology’s enthusiastic early adopters. In fact, a survey by Bowker Market Research revealed that 59 percent of Americans said they had “no interest” in purchasing an e-reader.

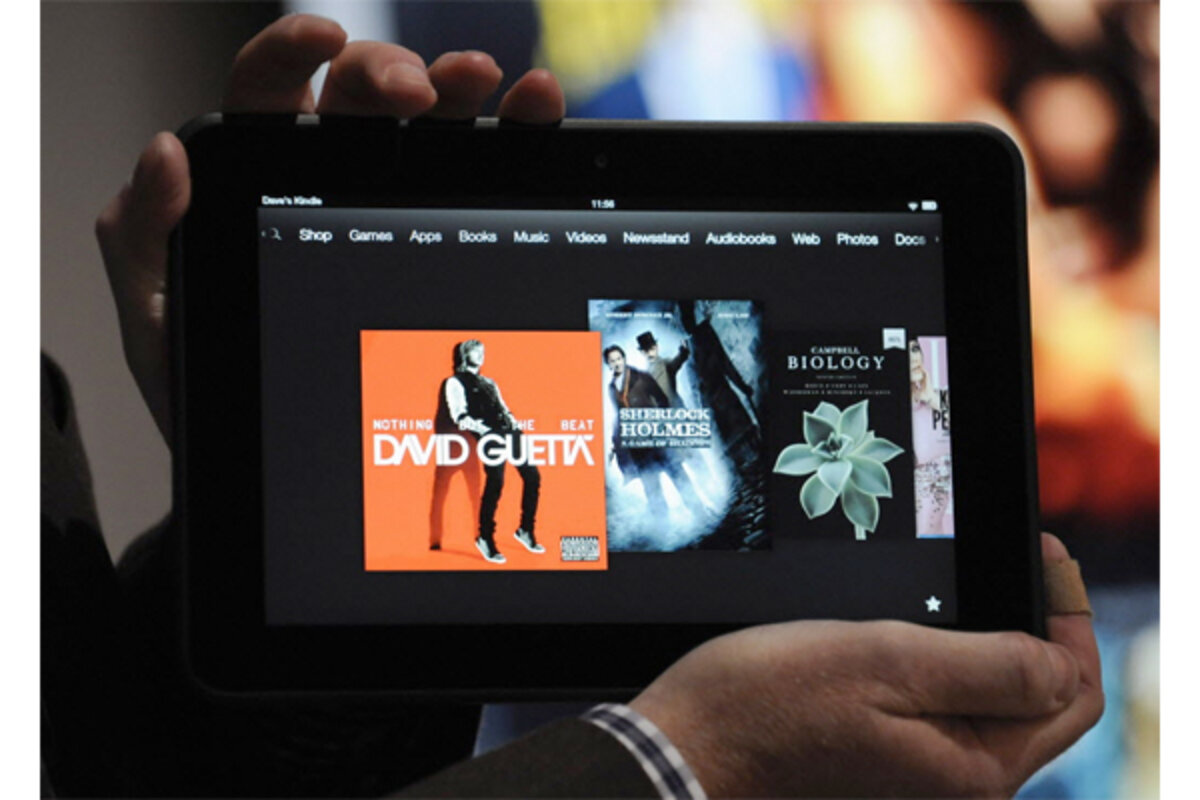

That may be because Americans are shifting from single-purpose e-readers to multi-purpose tablets. As the article pointed out, sales of e-readers are plunging while those of tablets are skyrocketing.

But Carr sees something deeper in the trend. E-readers have been particularly well-suited to genre novels, like thrillers and romances, “the most disposable of books” that we tend to read quickly and not want to hang onto. By contrast, he notes, we’re less likely to go digital on genres like literary fiction and narrative nonfiction. “Readers of weightier fare,” he posits, “seem to prefer the heft and durability, the tactile pleasures, of what we still call ‘real books’ – the kind you can set on a shelf.”

If that’s the case, argues Carr, e-books may be just another format, “an even lighter-weight, more disposable paperback” that readers use for certain genres, the same way we purchase mass-market fiction in paperback and cookbooks in hardcover.

Quite simply, print and digital serve different purposes, Carr concludes. The clinching evidence? According to Pew, nearly 90 percent of e-book readers continue to read physical books.

We’re very inclined to believe Carr’s argument, not simply because we want to, but because the evidence, statistical and anecdotal, is there. After all, for many of us, books are more than simply a collection of words that can be consumed on screens as readily as in print. Just as often, if not more, they bring to us tactile escape, visual pleasure, satisfactory heft, even pride and distinction as they trumpet their owners refined literary taste, sitting handsomely-bound on hardwood shelves.

As Carr concluded, “There’s something about a crisply printed, tightly bound book that we don’t seem eager to let go of.”

The reason his essay is spreading like wildfire on the web? So many of us are in deep agreement – and deeply relieved.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.