'Island of Vice' author Richard Zacks on Teddy Roosevelt's crusade to clean up NYC

Loading...

In the 1880s and 1890s, vice never slept in New York City.

Gamblers gambled, prostitutes prostituted, and thieves thieved, all under the not-so-careful watch of police on the take. Then an aristocratic little man named Theodore Roosevelt decided to make a big difference.

Cocky and sure of himself, Roosevelt became an unyielding force. He stalked the streets of the city in search of corrupt cops and made a stink about a police department that barely seemed to police anything.

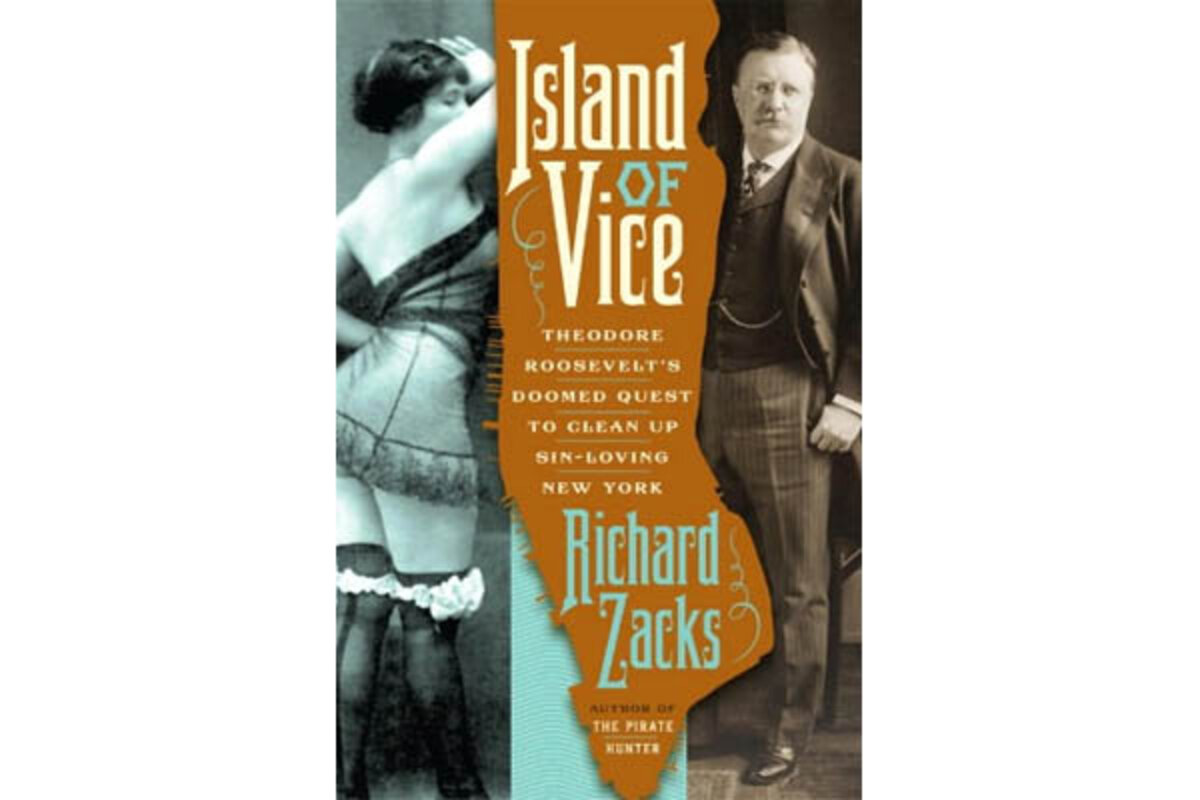

The ultimate fate of Roosevelt's efforts can be found in the title of historian Richard Zacks' new book, Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt's Doomed Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York. Never mind the giveaway of the ending. "Island of Vice" is a rollicking tale of hedonism and hypocrisy, crime and corruption, and one man's refusal to accept any of it.

In an interview from his home in New York City, Zacks – who previously made a splash with his book "The Pirate Hunter" – describes the sinful world of the Big Apple, Roosevelt's remarkable nighttime excursions and the guts of a man who refused to take get-lost for an answer.

Q: Just how bad was vice in New York City before the turn of the century?

A: It was extraordinarily full of vice. About 40,000 prostitutes were working in the city at the time, and there were many brothels, casinos and bookie joints. As for alcohol, clubs, and bars were supposed to close at one in the morning. But some couldn't remember being closed since the Civil War. All of these activities were illegal, so somebody had to pay off the police to make it happen.

Q: A few years ago, I interviewed Karen Abbott, the author of "Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys and the Battle for America's Soul." She told me that some upstanding people at that time thought it was a good idea to isolate vice into specific neighborhoods so they wouldn't corrupt the good people. Was this an issue in New York City?

A: There was a debate about having regulated red-light districts, which they had in most of the European countries. But the purest reformers rejected it. In New York City, a police official testified in 1885 that there should be red-light districts in the city. Cynical types thought he wanted to bring in one-stop shopping so he could collect money more easily.

Q: How rampant was prostitution at that time?

A: Emma Goldman, the labor radical, thought about 100 percent of single men and about 50 percent of married men went to prostitutes in that era. It gives you a sense of how widespread it was. The thing that most people now don’t realize about prostitution was that almost no respectable women went to the bars at that time. If a woman was in a bar at night, she tended to be a prostitute.

Q: As your book showed, one of the top anti-vice activists was an incredible hypocrite. Hypocrisy, of course, is common in many do-gooder movements, as is self-righteousness. But Roosevelt, several years from becoming president, doesn't come across as either a hypocrite or a prig. Is that your sense too?

A: He wasn't a hypocrite. He was a happily married man who wasn't sneaking off to the brothels. And he was by no means as self-righteous as some of the more church- and temperance-oriented reformers. But he did irritate people.

Q: Why did he think the city needed to be cleaned up?

A: He was a student of how corrupt the municipal governments of America were, how they’d been taken over by corrupt political organizations. He thought if he cleaned up New York, the Sodom of the country, it would have a snowball effect. If you could do it here, you could clean up any city.

Q: On some nights, he'd wander the streets of the city incognito and confront cops who weren't doing their jobs. What would happen?

A: The cops would say "I'm going to beat you!" or "I'm going to fan you!" with their nightstick. That’s when he was really popular. Nobody had so blatantly stood up to the cops like that. This 5-foot-8, 5-foot-9 little aristocrat confronting big Irish guys and lecturing them! I really don't think he did it as a publicity stunt, but it worked out to be one of the greatest publicity stunts. The city loved it at first, and the country loved it.

Q: What turned the city against him?

A: The crackdown on saloons being open on Sundays. When the city realized that this passionate man was actually going to really go through with it and never back down, he became despised in some quarters, and 30,000 people got in the streets to protest his policy. The immigrant cauldron of New York refused to be sober on Sundays. It was going to find a way around this crackdown, and it did, but not in a way anyone expected. They found a loophole, and suddenly everything backfired.

Q: What happened in the long term to Roosevelt's anti-vice and anti-crime efforts?

A: A lot of the things that Roosevelt cracked down on are now legal. He wanted to reinforce laws about not serving alcohol on Sundays; now bars can serve it on Sundays. He was cracking on off-track betting parlors, and now we have those. We have casinos not too far away, and the lottery. Society has just changed its opinions about a lot of the things that Roosevelt was cracking down on.

Q: What about the Wild West nature of New York City?

A: It has definitely gotten tamer. Here's an ultimate example: My teenage son called me. He said, "Don’t worry about me, I'm in Times Square." It's like a mall now. He doesn't know any better.

Q: What can we learn about Roosevelt in this whole story?

A: The big thing that still astounds me is that he did not back down even though he ultimately had a vast majority of the city and police department opposing him. When he took a poll, he took a poll of one: he asked himself what was the best thing to do. They don’t make politicians like that any more.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.