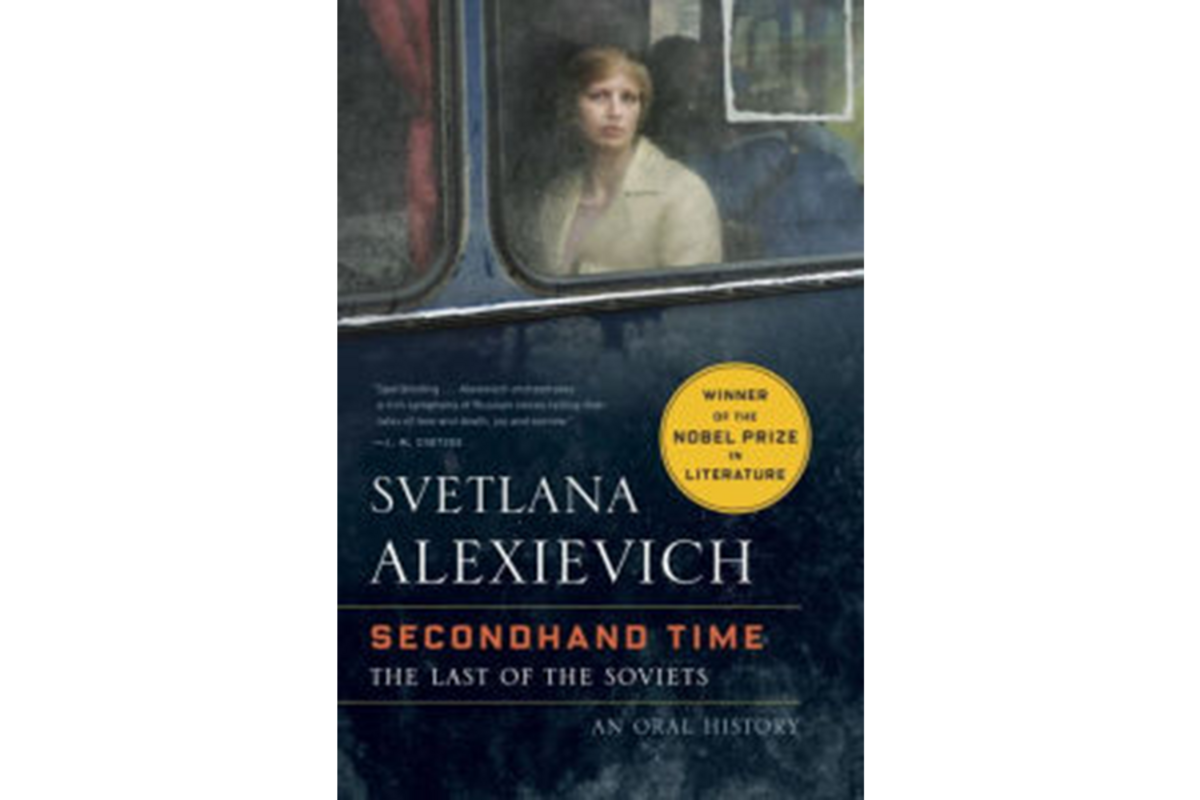

'Secondhand Time' records previously unheard witnesses to Soviet life

Loading...

Having grown up in and accommodated oneself to Stalin and then the post-Stalin Soviet Union, how disorienting it must have been to wake up in 1991 in a new country: “I can’t say what’s worse,” reflects a former citizen, “what we have today or the history of the Communist Party.… Life used to be bad, and now it’s outright frightening.”

Svetlana Alexievich, the 2015 Nobel Prize winner from Belarus, says almost nothing herself here. As she did in her previous translated oral histories ("Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War" and "Voices from Chernobyl"), she instead presents the voices of the generations “who had been permanently bound to the Soviet idea, who had allowed it to penetrate them so deeply that there was no separating them: The state had become their entire cosmos, blocking out everything else, even their own lives. They couldn’t just walk away from History.”

Alexievich has a magic potion for drawing out each member of the Soviet chorus: patience, curiosity and a camaraderie even with angry “Sovoks,” those bewildered and bewildering ones who miss the old days: “But … what’s the point of remembering all this?” says a retiree. “It’s as good as collecting the nails after a fire.”

“I’m rushing to make impressions of [the USSR’s] traces, its familiar faces,” explains Alexievich. “I don’t ask people about socialism, I want to know about love, jealousy, childhood, old age. Music, dances, hairdos. The myriad sundry details of a vanished way of life.”

Many of the hundred or so voices she quotes say they don’t trust words, memory or even Alexievich, and yet as they unwind, she gently prompts them into recollecting the details of everyday life and of their ideas of “freedom.”

Of course, believing in the freedom of speech in the former countries of the USSR continues to be dangerous for anyone determined to have a public and independent voice. Alexievich’s witnesses are those who haven’t had a say. She shows us from these conversations, many of them coming at the confessional kitchen table of Russian apartments, that it's powerful simply to be allowed to tell one’s own story: “I don’t know why I’m crying.… I already know all this.… I know my own life. But there you go.”

As a reader, so many passages clouded my eyes with tears, moments that Alexievich has waited for and caught and then transcribed and arranged. Decades ago, she realized she “should turn on the tape recorder so as not to miss this transformation of life – everyday life – into literature. I’m always listening for it, in every conversation, both general and private.”

But there's been nothing in Russian literature as great or personal or troubling as "Secondhand Time" since Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s "The Gulag Archipelago," nothing as necessary and overdue. And yet, could it be so, as one of the monologists remarks, that “You’ll write it down, publish it.… Good people will read it, they’ll cry, but the bad ones, the important ones … they’ll never read it”? Anyway, we can read it and be shocked by what people could and can do.

This is the kind of history, otherwise almost unacknowledged by today’s dictatorships, that matters. What is the cultural reluctance to confront the past? “In order to condemn Stalin,” answers one voice, “you’d have to condemn your friends and relatives along with him.” But what about documents? “I worked at an archive myself,” remarks another voice, “I can tell you firsthand: Paper lies even more than people do.”

While there are the confounding witnesses who wish for a Stalin’s return, others restore our belief in the possibility of redemption. Ravshan, who helps Tajik migrant workers in Moscow, muses: “You know what I am? I’m an alchemist.... We run a nonprofit – no money, no power, just good people....* Our results materialize out of nothing: just nerve, intuition, eastern flattery, Russian pity, and simple words like ‘my dear, ‘my good man,’ ‘I knew you were a real man and wouldn’t fail to help a woman in need.’ ‘Boys,’ I say to the sadists in uniform, ‘I have faith in you. I know that you’re human.’”

Those sentences burst into color because back in the USSR, the government believed in stomping out any unauthorized personal narrative or opinion. Thanks to President Putin, that brutal practice has revived. But, warns a former army officer, “Don’t make things up about what our people are like, saying that Russians are so good at heart. No one is prepared to repent.”

Random House has provided footnotes and a post-1953 (that is, post-Stalin) chronology for English readers. (The 2016 Russian edition of "Vremya Second Hand" has no need of chronology or footnotes but concludes with a useful author interview.) Bela Shayevich’s translation of the 2013 work is excellent, idiomatic; in the nearly 500 pages, there are only a few occasions where I was aware of a grain of Russian grammar or vocabulary.

"Secondhand Time," the fifth and, Alexievich says,** last volume in her “Red cycle,” is, among other things, the most ambitious Russian literary work of art of the century.

Bob Blaisdell, editor of "Essays on Civil Disobedience," frequently reviews books for the Monitor.

* All the other ellipses are Alexievich’s.

** See page 506 of the Russian edition (from an interview with her by Natal’ya Igrunova, the title more or less “Socialism Has Ended. But We Remain”).