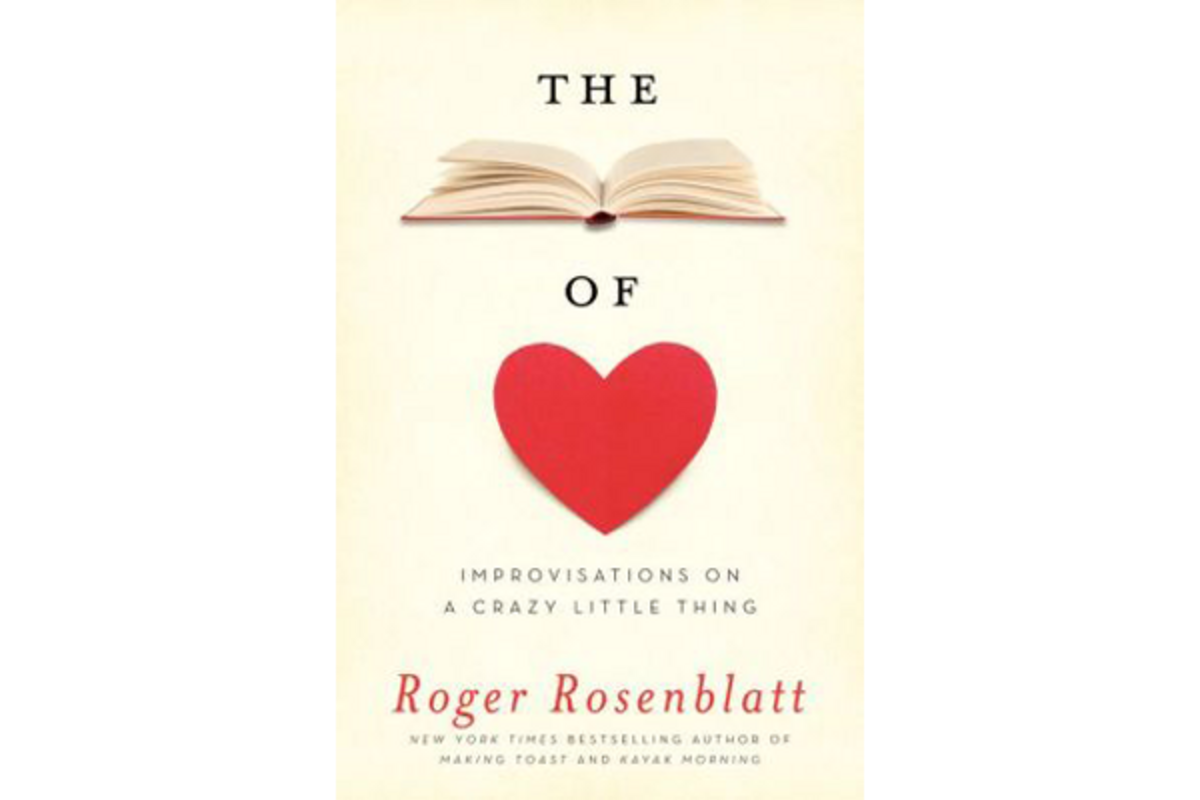

'The Book of Love' is Roger Rosenblatt's mediation on affection in all its forms

Loading...

Eudora Welty praised the essays of E.B. White as a place where the “transitory more and more becomes one with the beautiful.” That ideal also informs the work of Roger Rosenblatt, whose books often explore the fragile line between what endures and what does not.

In two tenderly exquisite memoirs, “Making Toast” and “Kayak Morning,” Rosenblatt chronicled his grown daughter’s sudden death from a previously undiagnosed heart condition, a tragedy that prompted him to consider what remains in the wake of deep loss. In his 2013 memoir, “The Boy Detective,” Rosenblatt contemplated the nature of the past. Is it an enduring presence, or a mere shadow obscured by the vagaries of memory?

The Book of Love, Rosenblatt’s latest book, tackles equally cosmic questions, offering a roving personal treatise on affection in all its forms – romantic love, friendship, parenthood, love of work and country. The subtitle’s reference to improvisation hints that Rosenblatt’s speculations will liberally indulge caprice – and even free association.

The experimental scheme of “The Book of Love” is a disappointing reminder that experiments don’t always work. Rosenblatt’s book-length essay, which includes everything from extended musical quotations to short fictions, personal recollections to tender valentines to his wife, reads more like a brainstorm for a book than a finished manuscript.

In an opening passage addressed to his wife of many years, Rosenblatt wryly notes how she “turns away at my contrived displays of wit. Embarrassed for me, who lacks the wit to be embarrassed for myself.” It’s a common enough sentiment for any spouse forced to endure a better half’s bad jokes, but the reader, like Ms. Rosenblatt, might also want to turn away at some of the authorial indulgences in “The Book of Love.” In a riff on things he loves, for example, Rosenblatt lists “Bette Davis, and Sammy Davis, Jr., and Harry Connick Jr., and Absorbine Jr.”. A little bit of this verbal horseplay goes an awfully long way, and in “A Book of Love,” that kind of cornball ribbing often flattens Rosenblatt’s typically graceful prose. It’s as if he’s rehearsing a stand-up act that’s not ready for prime time.

The book’s theme of improvisation becomes a label covering all manner of sins. At one point, with no apparent rationale, Rosenblatt throws in an excerpt from “Dogstoevsky,” one of his clever essays for Time magazine in which he comically recalls trying to read “Crime and Punishment” while a nearby canine barks its fool head off. It’s a polished piece of humor – one of the highpoints, in fact, of Rosenblatt’s marvelous 1994 collection of assorted journalism, “The Man in the Water” – but what’s “Dogstoevsky” doing in the middle of “The Book of Love”? The book frequently reads like a filibuster, a procession of bright oddities assembled not so much to say something, but to say anything.

Near the end of “A Book of Love,” Rosenblatt seems to offer a defense for the book’s hodgepodge sensibility. “So I sympathize with people who seek to create a unity of thought and emotion out of disorder,” he tells readers, “but I also believe that trying to fit parts into a whole makes each component smaller, less interesting and inauthentic. There is a life of parts as valid as the life of the whole. Simply noting is often enough. What right have I to give the universe a shape other than the one in which it presents itself without comment?”

Yet earlier in the book, in a passage listing good instructions for loving the world, Rosenblatt offers “’Don Quixote,’” ‘Paradise Lost,’ every Dickens novel, and ‘The Great Gatsby’” – all works of literature that advance just such context.

A mind as magical as Rosenblatt’s is bound to produce some gems, even in a literary project as helter-skelter as “The Book of Love.” He makes an insightful argument about why love at first sight isn’t as reflexive as we think, and there’s a touching account of how his grief for his own daughter connected him with a grieving mother after the school shootings in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. Rosenblatt’s evocation of musical giants, such as Ira Gershwin and Louis Armstrong, points us toward the equally sublime music of his sentences. Listen to these: “The moon is sky-high now, a small pale eye at the top of the dark. A light plane blinks by overhead. A letter from a friend, a photographer, whose child is gravely ill. He includes a picture of the boy. In a corner is the photographer’s shadow, like spilled ink.”

Rosenblatt mentions the ancient Greek belief “that the illuminations of the world derive from the rays our eyes project,” which he initially dismisses as “Hellenistic drivel.” But he essentially argues for love as just this kind of sustained attention. “The Book of Love” is a flawed if heartfelt summons to that way of seeing, a form of vision that compels Rosenblatt to gaze at his wife and conclude that “there was no light in the world but you.”

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”