In the memoir ‘Joyride,’ Susan Orlean turns her investigative eye inward

Loading...

Susan Orlean appears on my screen in a glowing, practically technicolor burst, in what seems to be a reverse greenhouse. She sits in a glassed-in structure, with a mass of tropical plants just on the other side. A 5-foot-tall queen of hearts playing card stands next to her. She doesn’t mention it.

This, she tells me, is her writing office, nestled in the hills of Los Angeles, but one could be forgiven for thinking she was reporting from a more exotic locale. After all, I’m speaking with one of the most celebrated journalists and writers of narrative nonfiction, a genre that uses literary and experiential techniques to report on its subjects.

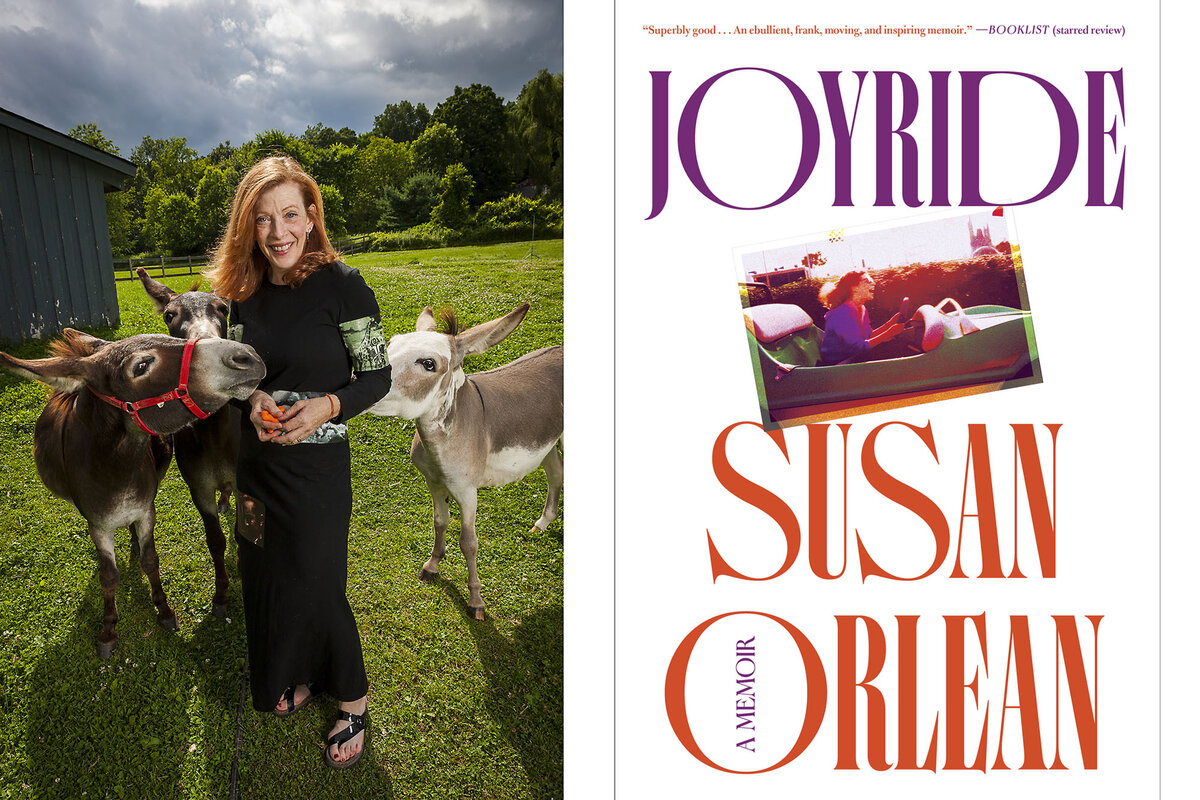

Orlean is the author of the breakout book “The Orchid Thief,” which inspired Charlie Kaufman’s script for the Spike Jonze film “Adaptation.” (Orlean’s role was played by Meryl Streep.) She also wrote The New York Times bestselling “The Library Book,” an investigation into the 1986 fire at the Los Angeles Central Library. On the page, she’s known for a keen reporting sensibility and for adding herself into the narrative. Now, she turns that investigative eye inward for her first memoir, “Joyride,” which arrives in bookstores Oct. 14.

Why We Wrote This

Susan Orlean’s approach to writing involves remaining a perpetual beginner, rather than becoming an expert. She dives into other worlds and subcultures, always chasing “the drive of ignorance into knowledge.”

She decided on the title because joy and exploration are at the core of her artistic and reporting practice. “It’s also a bit of a wink at the other meaning of joyride,” she says, flashing an almost imperceptible smile.

Orlean speaks at length, falling into a kind of absorbing digression, where for a moment you’re unsure where she’s taking you. But she always seems to swerve right back to the point. Several times in our conversation, she stopped herself, pausing, then redirected her answer with laser precision. “Let me put that differently,” she asked once, doubling back. And later, mid-answer, she looked off camera saying, “No, I’m not going to do anything with that,” an out-loud answer to a presumably internal train of thought.

This layered approach to our conversation is reflected in her work. In “The Orchid Thief,” she reports on an incident in which a man steals rare ghost orchids from a Florida swamp at the behest of and aided by the local Seminole tribe. This entry point leads to a sprawling exploration of the obsessive world of orchid collectors, Native American history, and other fascinating topics, going four or five layers deeper than any other writer-investigator might go. By Orlean’s own admission, she “tends to go rabbit hole.”

She does this with her other bestselling books, including one about the famous film-star dog Rin Tin Tin. In “Joyride,” Orlean says there was so much material to uncover about Rin Tin Tin that the text took her 10 years to write – longer than her son had been alive at that point. She remarks that her son probably thought his mother’s whole job was writing a book about a dog.

When asked about turning that investigative lens inward, Orlean gives a surprising answer. “At first, it was very awkward,” she says. “I spent a lot of time before I began feeling like: I just don’t know how to do this. I don’t understand how I could look at myself as a subject.”

Despite her many accomplishments, Orlean truly doubted that anyone was interested in her life. Orlean had so much trouble at the beginning stages of the project that she hired a friend to interview her, reversing her usual role, becoming the interviewee rather than the interviewer. This seemed to kick-start the process for her – from then on, everything clicked into place.

What follows is the development of a career and a creative practice – one marked by incredible skill, preternatural intuition, and extraordinary fortune. Orlean started off at alt-weekly magazines in Portland, Oregon (which she acknowledges, offhandedly, is a type of outlet that no longer exists), finding leads from billboards, signs on lampposts, rumors, and people on the fringes, alongside the usual techniques in the journalist’s toolbox.

From the outside, this seems like an unusual and unreliable way to find material – but it always seemed to work out for Orlean, who tracks down stories with an uncanny precision. At this time in her life, she reported on the influx of Hmong immigrants to the city, experimental musicians playing in abandoned warehouses, shocking crimes, an eccentric architect who threw it all away to become a puppeteer, and many others. Her process, she realized, was not becoming an expert in any one area, but always existing as the perpetual beginner, diving into new worlds and subcultures, always chasing “the drive of ignorance into knowledge.”

Later, as her career grew, she wrote stories for Rolling Stone, and became a contributor to The New Yorker in 1987, joining as a staff writer in 1992. She spontaneously sold her first book, “Saturday Night,” on a phone call with an editor interested in an entirely different project. Since then, she has produced eight more.

When asked about her propensity for immersing herself in her stories, rather than remaining an observer, Orlean focused in with an intensity that she hadn’t displayed earlier in the conversation. “I feel like those things can coexist quite comfortably,” she says. “You feel like it’s a delicate thing to both deliver deeply researched historical or contemporary information and then manage somehow to also then write the more intimate, first-person stuff.”

It’s clear that this is something that Orlean has thought a lot about. In her work now, she deftly balances both roles, dancing across that razor’s edge as skillfully as an acrobat. As this is a memoir, going back some 25-odd years, and even further, to her childhood, I felt it prudent to ask her about the reliability of memory as a reporting tool. Not just her own, I assure her, but in general.

This is another thing she clearly has thought a lot about. “The word to live and die by is ‘transparency,’” Orlean says. “Readers are smart, and you can say to them: ‘This is how I remember it.’ I see no gray area between true versus imagined in my reported pieces. None of that is acceptable to me. In memoir, it’s trickier because you are relying on your own flawed memory.”

As I prepared to move on to another question, Orlean sunk her teeth into the subject a little deeper, continuing on.

“And listen, it worries me terribly that I get asked by journalism students, ‘Is it OK if some of what you write isn’t true?’ And you think, yeah, it matters a lot. ‘Well, does everything have to be true?’ And you think, ‘Well, wait. There’s this amazing art form called fiction.’”

“Joyride” reads not just like a memoir, but a snapshot of a media landscape of a particular time. Most of the world of journalism and publishing that she came up in doesn’t exist anymore. So, more than anything, it’s a manual of sorts, a guidebook to both the craft of nonfiction writing and the joy of the writing life.

“Writers are both born and made,” Orlean tells me. “I always looked at the world with curiosity and maybe more openness than the average bear. Anything strange or different I think: ‘Oh, what’s that about?’”

As Orlean talks about her career and process, both in her book and in conversation, there are clear themes that emerge. The importance of chasing the thrill of discovery. Being able to shape your world by the skin of your teeth. That something extraordinary is waiting for you under every rock, in every nook and cranny, if you’re willing to step in, look just a little closer.

But there is another echoing feeling, something unsaid just under the surface. An implication: I did this. With work, you can, too.