Iran has largely crushed protests, but a spirit of defiance still burns

Loading...

| LONDON

In her high school classroom in northwest Iran, the math teacher strives to ensure that her female students don’t lose sight of what they achieved taking part in unprecedented anti-regime street protests – even if those protests have now largely been crushed.

“There is no doubt the protests have fizzled out,” says the teacher in the city of Sanandaj, epicenter of the protests in Iran’s largely Kurdish northwest, where officials used direct military force to quell dissent.

“Look around, except for the 40th day [funeral] memorials, few rallies are being held these days,” says the math teacher, who gives the name Yosra. “But does that mean it’s over? Absolutely not.”

Why We Wrote This

In Iran’s Islamic Republic, anti-regime protests have ebbed and flowed. For now, fierce public expressions that harnessed women’s outrage have been brutally suppressed, but the resolve to find a path to change hasn’t.

Back in November, when the protests were raging, Yosra told the Monitor that her students were unfazed by the steady flow of threatening messages from education authorities. Her students, she said then, “are a different species; they won’t accept humiliation.”

Yet as the street protests themselves disappear, resistance today means “keeping awareness among my students, dissecting the regime’s nature, and reminding them of their mission to press ahead and never allow this to become a new normal,” she says.

“That’s poison,” she adds, “the very exact poison that killed off the desire for change in my generation, that destroyed the bravery within us.”

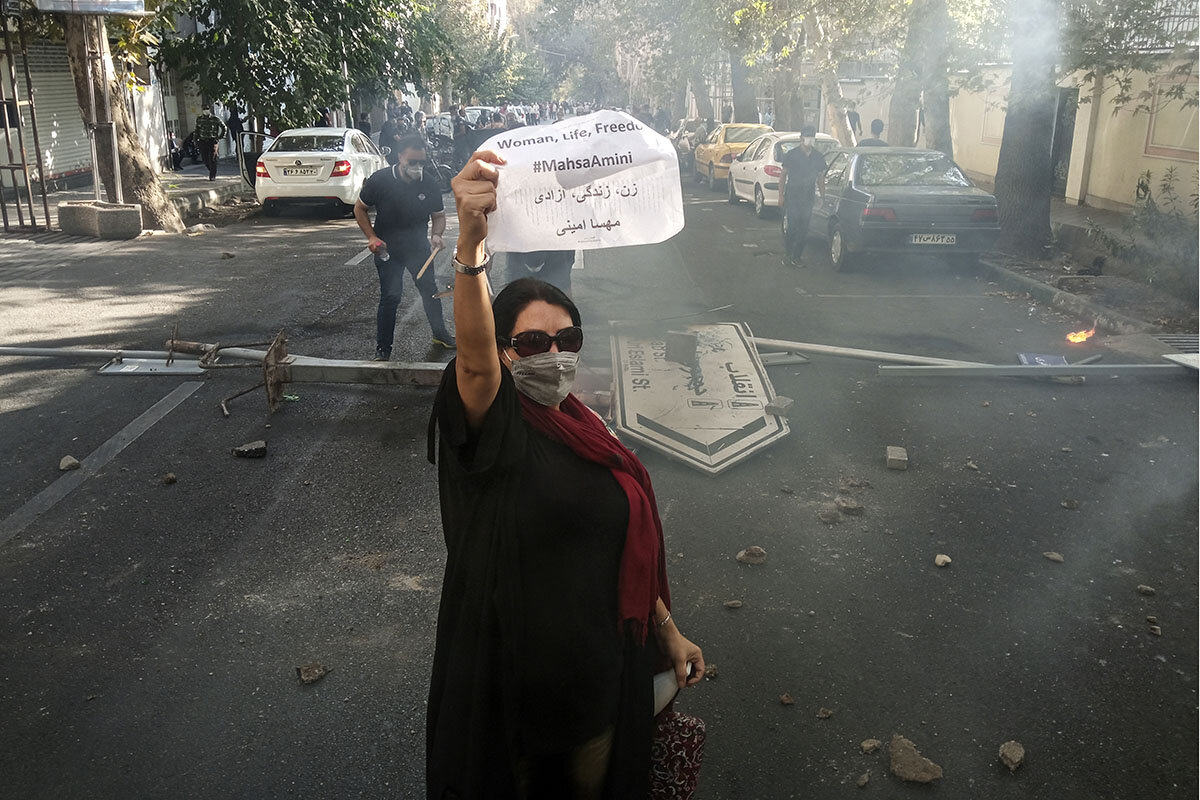

The nationwide protests, billed as Iran’s first feminist uprising, were triggered in mid-September by the death in police custody of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, for allegedly breaking hijab laws by showing too much hair from beneath her headscarf.

As Iran marks the 44th anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution Saturday, hard-line ideologues are gloating that regime enforcers have, once again, bottled up widespread discontent that threatened more than ever the pillars of their self-proclaimed “Government of God.”

Human rights groups estimate that some 500 people have been killed, hundreds more wounded in the eyes – often shot in the face at close range, in what appears to have been a systematic effort – and 20,000 arrested in the clashes and government crackdown.

Ambitions put on hold

For months, rage over Ms. Amini’s death, and then over the government’s response to the protests themselves, had spread to more than 130 cities, propelled by chants of “Woman, Life, Freedom!” and the public burning of headscarves and portraits of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

With long-standing grievances over Iran’s weak economy, corruption, and clerical misrule swelling the ranks of protesters further, some had even predicted that the regime would fall. Many protesters vowed to fight to the death, if it would expand freedoms and restore dignity to Iranian lives.

Instead, a mostly younger generation that defiantly demanded the end of what they consider a decrepit and hidebound leadership has witnessed its own ambition for change put on hold in the wake of the systematic and lethal crackdown.

“Does that disappoint me? It’s hard to say. … This regime has proven that it will go to all lengths to crush us and has no boundaries,” says Yosra, noting that the risks to continue had grown too great.

“I mean, it’s our young people being killed by a regime that has no shame and looks you in the eye and denies the killings,” she says.

Past episodes of street protests have sometimes yielded change, instituted by an Islamic Republic that has proudly claimed the broadest popular support, as well as a divine mandate. Few of the republic’s founding revolutionaries forget that it was their own mobilizing of anger on the streets, resulting in massive protests for months on end, that did so much to topple the pro-West shah and his security apparatus and armed forces, which appeared all-powerful at the time.

Providing a safety valve for grievances to dissipate has therefore been a frequent tactic. Indeed, Ayatollah Khamenei may have given the sense of leaning toward compromise when he announced in early January that women wearing a loose hijab were still “our daughters” who should not be treated like anti-revolutionary enemies – though he also declared that wearing the hijab remained an “inviolable necessity.”

And Mr. Khamenei, in keeping with tradition on the eve of the revolution’s anniversary, on Feb. 3 pardoned an estimated 19,000 prisoners – among them some who had been detained during the protests. (Nevertheless, this week several high-profile protesters were filmed outside Evin Prison after their release, chanting defiantly that “the tyrannical regime must be overthrown.”)

Signals of retrenchment

But other steps make clear that authorities, instead of finding a middle path, are doubling down on strict hijab rules and other forms of dissent.

Already four young protesters have been executed for moharebeh, or “waging war against God,” with more than 100 other cases pending, according to the Norway-based Iran Human Rights group. The hard-line judiciary has also demanded “decisive” action by the police and outlined tough new penalties – including 10 days to a decade in jail – to stop the removal of head coverings in public, an act widely embraced by women since the protests began.

Signals of retrenchment also include the mid-January appointment of hard-line cleric Abdolhossein Khosropanah to head the powerful Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, which outlines hijab and other social policies.

He has said that protesters should be spared “no mercy” and be put to death by “crucifixion.” In an interview with Fars News Agency, Mr. Khosropanah described how – even before 1979 – he used to personally fire a slingshot at women he saw wearing their hijab loosely. He apparently stopped the practice when his father expressed concern for the women’s safety, and afterward only threw water at them.

Another signal is the appointment in early January of Brig. Gen. Ahmad Reza Radan to command the police. He is sanctioned by the U.S. government for “beatings, murder, and arbitrary arrests and detentions against protestors” that he was responsible for as deputy chief of Iran’s National Police, during the lethal crackdown that ended post-election protests in 2009. Before that, as Tehran’s chief of police, he doubled the size of police forces cracking down on un-Islamic dress in what he called an “unstoppable” campaign.

Even without those extra measures taken by authorities, protesters have described feeling continuing pressure for their defiance.

Among them is Romina, who told the Monitor in detail about her 3 a.m. arrest in late September, the denigrating physical and sexual abuse and death threats she endured, and the inspiration she found – in her own inner fortitude and among younger, incarcerated fellow protesters – to return to the streets.

Romina recounted how her interrogator in the northwestern city of Kermanshah twisted her hair in his hand, and told her the “outcome of your revolution” would be that she would hang by that hair.

Since her release, Romina has received four calls from private numbers, a typical sign that they are from the intelligence unit of the Revolutionary Guard.

“They keep threatening me, telling me that they are closely watching every move, and that I could get arrested again,” Romina says now, adding that she remains unbowed. “They use the same sexist language and expletives. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of sleep, with nightmares that they are at the door, trying to take me away again.”

“Hoping for foreign support”

She says she keeps up her criticism of the regime and boosts protest messages on fake social media accounts, and continues to flaunt hijab rules. But she was recently forced to return home for a headscarf when she was not allowed into the water department to follow up on a bill, after the guard refused her entry.

“I know many who have become disappointed after four months and no tangible outcomes,” says Romina. “But I keep telling them that we have a long way ahead and there are surely ups and downs. It does not happen overnight, does it? What we need at this stage, where the repression is endless, is outside support. We are hoping for foreign support.”

“If this regime does not feel the pressure, it will just have a free pass to kill us all,” adds Romina. “It’s like an abusive and addicted father. If he is not confronted, he feels he can do everything without facing any punishment.”

Yosra, the math teacher, also uses a family example, but one that looks to the past to understand how Iranian protesters demanding change today should proceed.

“In our days, every now and then the regime came out with brute force, pushed people back into their homes, and things really died down, because we were intimidated,” she says.

“Our parents were part of this, because they kept telling us about the consequences – not that they supported the regime, but because they feared for our safety, and that’s how the regime managed to survive,” Yosra says.

“Now things are different,” she adds. “This new generation has been raised by parents who sincerely want their children not to suffer the same fate as theirs.

“I don’t know what will happen in the months to come, but trust me: It’s not like the push for regime change has become any less powerful. It’s there.”

An Iran researcher contributed to this report.