Editor who led independent journalism in China resigns

Loading...

BEIJING – Independent journalism in China, never a robust phenomenon, has taken a body blow with the resignation from the country’s top investigative business magazine of its pioneering editor.

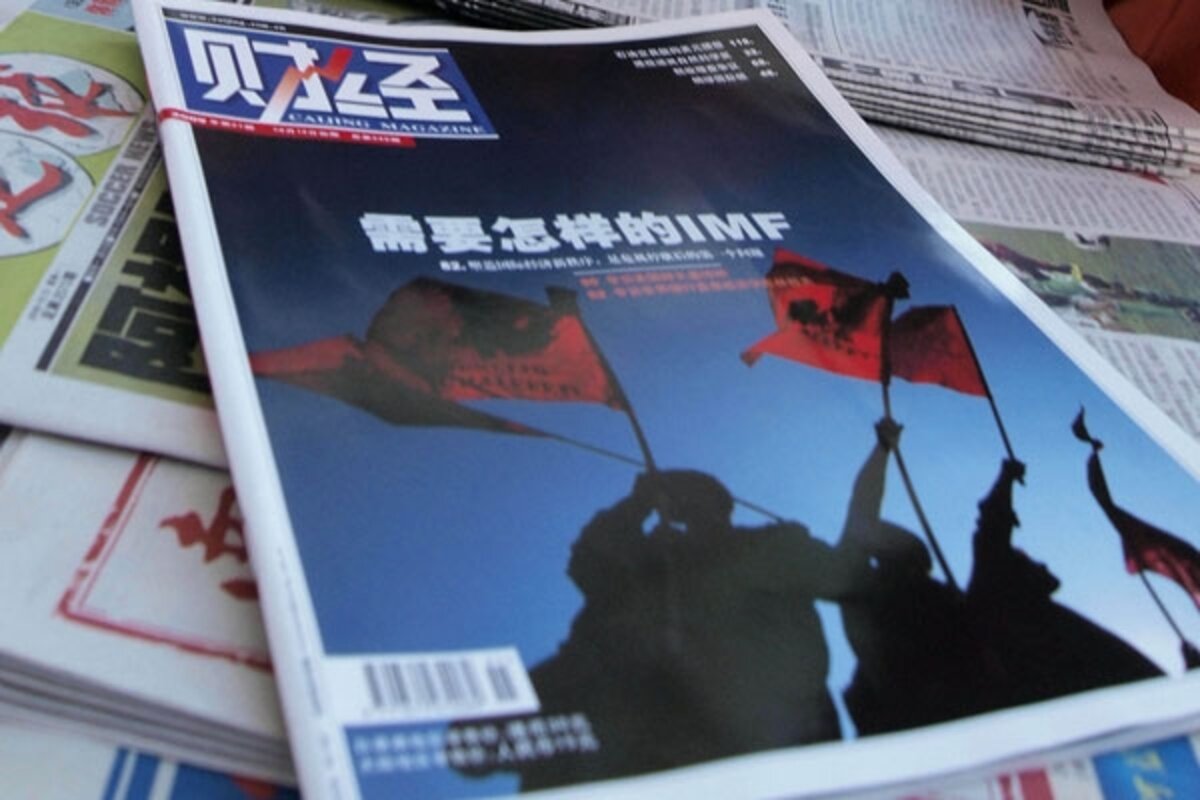

Hu Shuli, editor and founder of the biweekly Caijing, stepped down Monday after a prolonged tussle with the magazine’s owners over financial and political differences.

“This is disastrous for professional journalism in China,” says David Bandurski, head of the China Media Project at Hong Kong University. “Hu Shuli embodied the professional spirit. Her departure is a huge discouragement to Chinese journalists.”

“The course of advancing freedom of expression is not very straight … and there is not a very strong force behind it,” adds Gong Wenxiang, a journalism professor at Peking University. “I don’t think the environment for people like her [Ms. Hu] is very positive.”

Caijing, founded 11 years ago, has made a name for itself with investigations of corporate and government corruption that have put a number of people behind bars. Such reporting, however, and the magazine’s broadening coverage of stories beyond the business world, has made Hu some powerful enemies in the ruling Communist party.

They reportedly put pressure on Caijing’s owners, the Stock Exchange Executive Council, to rein Hu in. Her riposte – a bid to change the magazine’s shareholder structure to strengthen its independence – ended unsuccessfully with her resignation.

“Caijing is one of a kind,” says Xiao Qiang, head of the China Internet Project at the University of California at Berkeley. “The fact Hu has to leave symbolizes the failure of that kind of experiment. The space she created has been closed down, and I don’t think anything like Caijing will come up soon."

Ms. Hu, apparently, does not agree. Though she has refused to comment on her resignation or her plans, colleagues say she is seeking investors to launch a fresh media operation similar to Caijing.

She would be bucking the trend, however. Signs two years ago that the Chinese government was prepared to tolerate some independent reporting on issues such as the environment have all but disappeared, says Mr. Bandurski.

The Communist party’s message now, he says, “is that control is top priority, and they won’t be moving in any other direction soon.”

In a speech Sunday to mark Journalists’ Day, the party’s top ideologist Li Changchun urged newspapers and other publications to “adhere to the party’s control on media and cadres to ensure that the leadership in journalism and propaganda work is firmly in the hands of people who are loyal to the party.”

That caution, suggests Professor Gong, suggests that today’s leaders “are not as confident as the last generation.”

It also dampens hopes for liberalizing political reforms to match the economic reforms that have powered China’s growth over the past three decades.

“Beijing’s political landscape cannot tolerate a publication like Caijing any more,” says Dr. Xiao. “Hu Shuli’s departure is another clear example of the [government] policy to refuse political reform.”

Press freedoms and political reform are intimately linked, argues Bandurski. “There needs to be more political reform for any media breakthrough…but it is impossible to have substantive political reform without moves on freedom of information,” he says.

While some commercial publications, such as those owned by the Southern Media Group in Guangzhou, continue to push the envelope occasionally with their coverage of politically sensitive issues, the tide is running against them, Bandurski fears.

“It’s a very precarious environment for that kind of journalism,” he says.