New Wave filmmaker Godard lived France’s love-hate relationship with US

Loading...

| Paris

A line snakes down the street outside La Filmothèque, one of Paris’ cult art-house cinemas in the famous Latin Quarter. A few people are here to watch “Vivre Sa Vie” (“My Life to Live”), the 1962 film by radical French-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who died Tuesday at the age of 91.

But most are here for the classic American film “Thief,” directed by Michael Mann.

“I usually only watch old movies, ones that represent the golden age of cinema,” says Bernard Thoral, a regular cinemagoer. “I love American film noir. Godard? It’s not really my thing. I’ve never seen one of his movies.”

Why We Wrote This

Mold-breaking French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard’s revolutionary reputation still does not make him more popular with cinemagoers than American directors, who dominate French screens.

It might come as a surprise that any French cinemagoer would deign to watch an American film the day after the death of a cinematic legend such as Mr. Godard, who shaped the improvisational, informal, New Wave cinematic style in the 1960s, creating a veritable revolution in French filmmaking.

But American cinema has long been a hot cultural commodity in France, sparking a deep and long-standing love-hate relationship that has played out amicably – and defiantly – over the last century. France’s simultaneous fascination with, and disdain for, American culture has produced waves of both adoration and scorn, and ultimately, say some critics, made France a victim of American cultural imperialism.

The iconoclastic Mr. Godard epitomized this ambiguity, spending decades imitating, quoting, and paying homage to American cinema, before rejecting the “Americanization” of the world and falling out with the Hollywood machine.

“The French have a very contrasting image of the U.S.,” says Bruno Péquignot, professor emeritus of arts and culture at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University in Paris. They feel that “on one hand, its writers and filmmakers can be extremely subtle, intelligent, and capable of grasping nuance, and on the other they can be brutes, as if they just stepped out of a cave.”

The “cultural exception”

French cinema is revered both at home and abroad; going to a movie theater here is a sophisticated affair – no loud crunching of popcorn allowed. And until World War I, French cinema dominated markets around the world, supplying 60% to 70% of films shown globally. Then, however, its influence began to dwindle and the U.S. film industry became the most important in the world.

French cinema didn’t make its comeback until the late 1950s, when Mr. Godard entered the scene alongside fellow New Wave filmmakers François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol.

It was around that time that the French government decided that French culture needed protecting. French Culture Minister André Malraux promoted the idea of a French “cultural exception,” which gave cultural products a special status in international trade negotiations.

“Malraux was seen as a hero of French cinema, defending it against the ‘big, bad American cinema,’” says Jonathan Broda, a film historian at the International Film & Television School Paris. “I say that with irony, but American cinema still dominates French screens.”

Ever since the Malraux era, the authorities have been fighting to provide space for French culture to bloom. Jack Lang, culture minister in the mid-1980s and again in the early 1990s, was particularly critical of American dominance, calling for a “crusade” against this “financial and intellectual imperialism that ... grabs consciousness, ways of thinking, ways of living.”

By the early 1990s, American films accounted for more than 60% of French box-office revenues, according to the Ministry of Culture. In 2013, France’s then-Culture Minister Aurélie Filippetti successfully called for the audiovisual sector to be excluded from free trade negotiations between the United States and the European Union, so that it could enjoy government support.

But despite government efforts and a revitalized French filmmaking industry, American cinema continues to reign. In 2019, only one French film was among the top 10 box-office hits in France – the rest were American, the majority distributed by Walt Disney Studios.

“More than any other medium, cinema epitomizes cultural imperialism,” says Mr. Broda. “If James Dean wore blue jeans, everyone wanted to wear blue jeans. If Marilyn Monroe drank Coca Cola, everyone drank it. Cinema has become the best ambassador of the American economy.”

Eternally controversial

Mr. Godard had a similar fascination with American cinema, and his breakout film “A Bout de Souffle” (“Breathless”) took inspiration from the original U.S. version of “Scarface,” released in 1932. In 1968, he accompanied his film “La Chinoise” on a tour of American universities and met Black Panther activist Kathleen Cleaver in Oakland.

But he had already begun to mock certain aspects of American life in his 1963 film “Le Mépris” (“Contempt”), and when the Vietnam War broke out, Mr. Godard was not shy about expressing his opinions on America’s military involvement. By the 2000s the relationship had soured, and in 2010, when Mr. Godard was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement, he said it meant “nothing” to him and did not go to collect it.

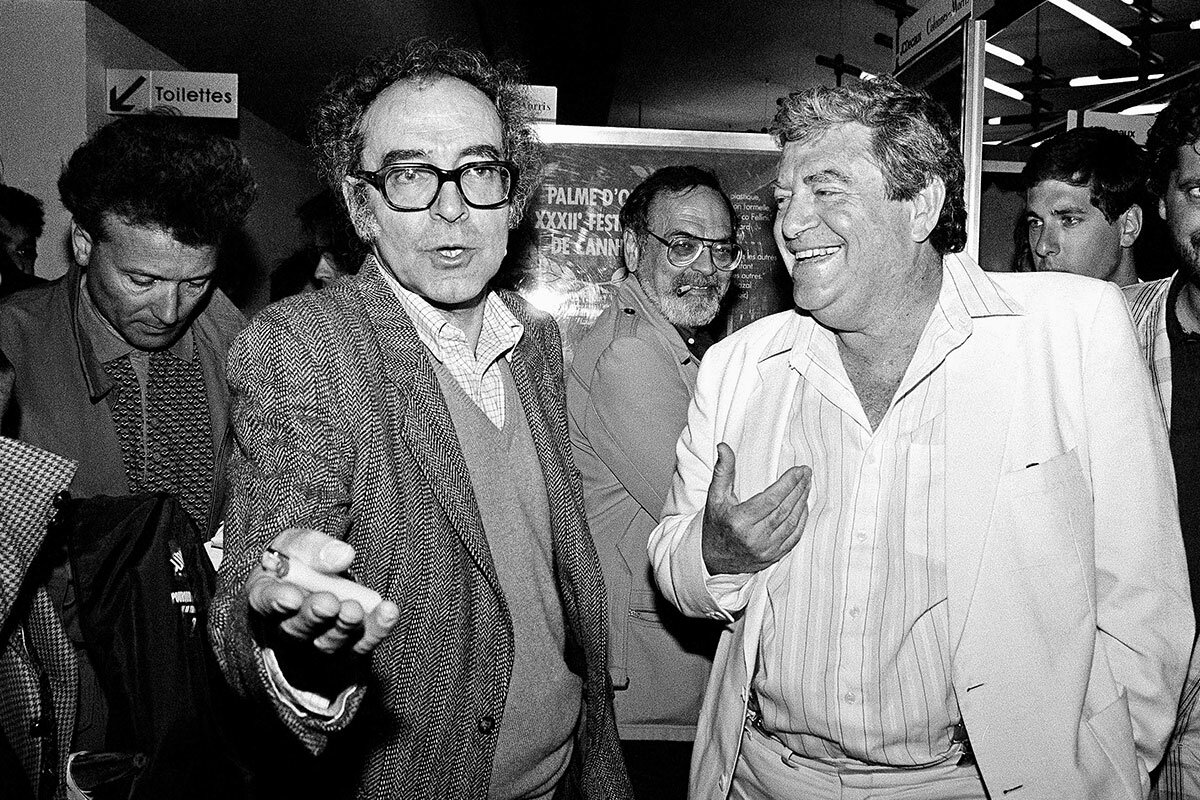

Though he remains a revered symbol of French cinema, Mr. Godard was eternally controversial, both politically and cinematically. (He once said that “a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end – but not necessarily in that order.”) Though two of his films won prizes at the Cannes Film Festival, they never received the top award, nor did he ever win a César, France’s equivalent of the Academy Awards.

At La Filmothèque, owner Jean-Max Causse is happy to see people turning out for Mr. Godard, even if he knows his films are not to everyone’s taste. Mr. Godard was one of Mr. Causse’s first customers when he opened his first cinema in central Paris in 1967. He remembers Mr. Truffaut arriving with Catherine Deneuve, and Mr. Godard complaining loudly about the volume of the music.

“He wasn’t as well liked as Truffaut, but like these other young filmmakers who had never been to film school, he shook up conventions,” says Mr. Causse. “French cinema is in a bit of a state of crisis right now. In the U.S., cinema is starting to rise from the ashes, but it’s the end of a certain era.”

Christophe Kaprelian, a local photographer, came to see “Vivre Sa Vie” to pay homage to that era, and his respects to a legend.

“I love American classics by Hitchcock or Stanley Kubrick. They inspire me,” says Mr. Kaprelian, who goes to the cinema at least 10 times a month. “But today, I had to come see Godard on the big screen.”