Germany has money. Why donãt its schools have computers?

Loading...

| Berlin

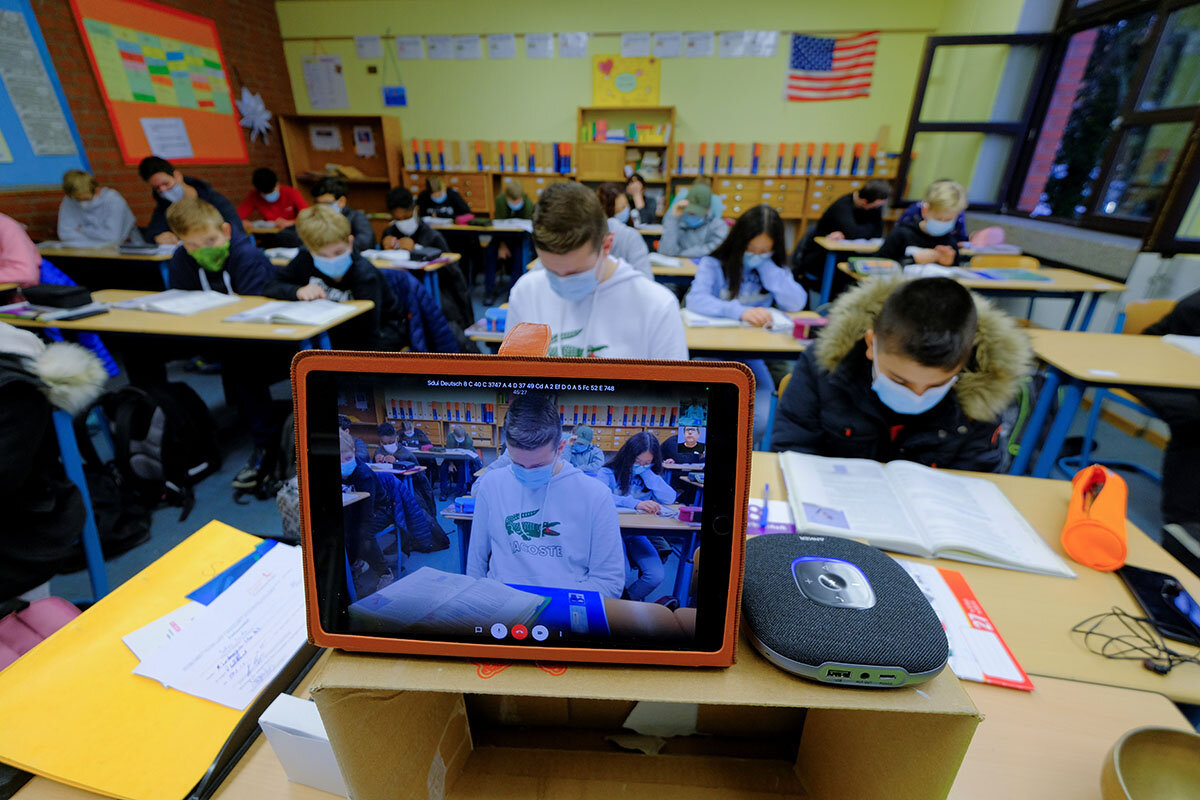

Germany may be Europeãs wealthiest country, but you wouldnãt necessarily know it from its classrooms. Take those in Bremen, where Tim Kantereit has been working hectically to introduce digital tools and concepts to his educational colleagues.

The former math and geography teacher found himself ãalways five to six years aheadã of the curve in Germany, where computers, software, and other technology are sorely lacking in schools.

ãIãve fought with teachers who question why digitization is the future, and why it even has to be considered,ã says Mr. Kantereit, who has trained teachers for the last seven years of a two-decade career in education. ãSo much discussion about why everything has to be digital.ã

Why We Wrote This

Germanyãs classrooms are oddly old-school when it comes to technology. But the past year has dramatically shown many teachers how technology can shape education for the better.

Only 1 in 3 students has access to online learning platforms, compared with more than half in other countries across the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. A ã˜5 billion ($5.9 billion) federal digitization plan, the Digital Pact for Schools, passed two years ago has been slow to pick up steam. Itãs only with the pandemic that a public spotlight has been turned on the effects of abysmally poor digitization levels, and the accompanying lockdown has prompted a radical rethinking of the need for digital infrastructure and teacher training.

ãWe Germans are programmed to have an organized system that constantly thinks in hierarchy, but we forget the world has moved forward at great speed,ã says Matthias Kostrzewa, digitization officer at Ruhr Universityãsä»Professional School of Education in Bochum. The pandemic ãhas been a magnifying glass to show the problems we had not just in schools, but all areas of society. And itãs accelerated the bureaucratic work [of digitization].ã

ãOven vegetablesã

When the pandemic hit and schools shut down in Germany, it became very quickly apparent that not every child had access to a tablet or smartphone, much less a Wi-Fi connection. By last summer, the government had dedicated ã˜500 million to digital hardware, but the flowchart for the funding was so complex ã feds to state to schools to families ã that it wasnãt clear students were getting the devices quickly.

ãThatãs why we lobbied that families who already get social services should apply for money from employment offices directly and buy the laptop themselves,ã says child social security expert Jana Liebert.

Itãs these kinds of bureaucratic hurdles, made ever more obvious amid the pandemic, that have tripped up Germanyãs massive education digitization effort in normal times.

The federal governmentãs Digital Pact for Schools focused on digital equipment, but infrastructure is only one part of whatãs needed. Revamping pedagogy and training teachers are also important pillars.

Yet how does one start bringing the education system into the modern era, when the federal government has the funding, yet education is administered by each of Germanyãs 16 states, with many schools given latitude on how to implement initiatives?

Further, thereãs confusion around what exactly digitization is. ãMy example is oven vegetables,ã says Mr. Kostrzewa, the digitization officer. ãIf we order this at a restaurant, we all have an idea of what it might be, but itãs not the same as what the restaurant imagines.ã

Digitization can mean technical devices and Wi-Fi, which are in short supply still in rural districts, but it can also encompass the platforms required for distance learning, as well as utopian or dystopian discussions such as, Do we even need teachers in the future?

Through mid-2020 only a fraction ã ã of a now ã˜6.5 billion committed to Germanyãs digitization effort has been distributed across the 16 states, which oversee education. Approaches have depended heavily on each region, whereas cities also have varying approaches, from soup-to-nuts revamps of existing curricula to simply purchasing 27,000 digital devices as Cologne has.

Whatãs clear is that the pandemic has illustrated the urgent need for digitization, which has helped speed up the bureaucracy around the process.

ãSurely the pandemic has accelerated the bureaucratic work of digitization, and also highlighted the problems of inequality,ã says Mr. Kostrzewa. ãIn distance learning, a lot depends on how much parents can support the child. When corona is over we will be longing for normality, but I hope we remember the good parts of the development and take those aspects with us into the future.ã

What does digitization mean?

When digitization works, itãs a long process thatãs baked into the fabric of a school community.

Micha Pallesche, a principal in the midsized southwestern city of Karlsruhe, remembers when his school first tried to ãdigitizeã teaching and learning. ãFor the schoolbooks, they just made the books into PDFs,ã says Mr. Pallesche, principal of Ernst Reuter Community School. ãIt was the exact same thing. Only a PDF.ã

ãThe question that became important is to think about what ãdigitizationã actually means,ã he adds.

That question prompted a long journey, started six years ago, to begin ãdigitizationã from scratch. ãWhatãs outside of what people think digitization is? Itãs not just about putting a smart [whiteboard] in the classroom,ã says Mr. Pallesche.

The schoolãs transformation started when its home state of Baden-Wû¥rttembergä»voted to support alternative ãcommunity schools.ã The city of Karlsruhe approached Ernst Reuter Community School and asked if it would be a pilot project. Financing came from the local school board, with other funds coming from the federal Digital Pact, grants and prize money, and donations from corporate foundations. (A pandemic-related government payout also helped buy a few dozen iPads.)

Then, over six years, school administrators tapped a community brainstorming effort, which brought in different viewpoints and expertise. Students were central to decision-making, with parents and teachers also involved.

What resulted is a school that now deploys, yes, whiteboards, but has also completely transformed teaching and learning processes. Funding helped purchase everything from iPads to video production software to 3D printers. It also overhauled teacher training.

Flipped classrooms

One of the schoolãs proudest transformations is what Mr. Pallesche calls the double ãflippingã of the flipped classroom.

A flipped or inverted classroom requires students to watch content videos prior to class. Then students come to class already briefed, so the teacher can use in-person time to discuss and mine new depths understanding, rather than waste time introducing basic material.

Here, the school innovates further. It flips the ãflippedã classroom once more to make the students the teachers. Students create videos and write books, and become producers of their own content. ãThey use the four Cãs: create, collaborate, communicate, be critical,ã says Mr. Pallesche. ãThey have to understand the topic to be able to teach it. Theyãre learning much more sustainably this way.ã

The pandemic prompted the school to further innovate. By the second lockdown, teachers began experimenting with ways to connect subjects such as chemistry and biology along a single theme, such as energy. ãWe are networking these subjects now,ã says Mr. Pallesche. ãThe world outside isnãt divided into subjects ã itãs all connected.ã

Ernst Reuter Community School is now Germanyãs first ãsmart school,ã even though itãs housed in an old building from the 1960s. ãPeople think they need the best infrastructure, but thatãs not true. We just used these rooms and space differently,ã says Mr. Pallesche.

The average German public school has a long way to go, though the pandemic has given digitization a heightened sense of urgency. ãThese ideas I tried to implement a couple of years ago are now widespread in Bremen,ã says Mr. Kantereit, the teacher trainer and author of ãHybrid Teaching 101.ã

One thing Mr.ä»Kostrzewa,ä»the digitization officer, hopes will be reexamined in the future is societyãs obsession with having a daily presence in school. Maybe three days a week is enough. Politicians also desire too much control over change, he says, and should perhaps embrace the fact that reform can be overwhelming.

Longer term, the education system is moving in the right direction, says psychologist Thilo Hartmann. ãThatãs a positive thing, because digitization can help support students who are chronically ill or otherwise challenged. ... It allows a flexible education.ã