Trump sees a ‘con’ in climate change. Xi sees cash.

Loading...

| London

More than 40,000 delegates from nearly 200 countries are getting down to work this week in the Brazilian city of Belém, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, for what is looking like an increasingly forlorn task: to slow and mitigate the overheating of our planet.

But while their work at the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly known as¬ÝCOP30, certainly matters, this latest gathering comes amid a dramatic shift ‚Äì along with an improbable glimmer of hope ‚Äì in the politics of climate change.

Whether, and how, the world adopts clean energy technologies ‚Äì¬Ýreplacing carbon-heavy oil, gas, and coal ‚Äì¬Ýhas come to depend less on these annual get-togethers than on the domestic political agendas of each individual nation.

Why We Wrote This

As the COP30 climate conference gathers in Brazil, Beijing and Washington have taken opposing positions on climate change. Donald Trump calls it a “con.” Xi Jinping has invested billions this year on green tech. Whose view will prove more prescient?

And no nations matter more than two energy superpowers with diverging interests, and with increasingly divergent approaches to climate change: the United States and China.

U.S. President Donald Trump recently branded climate change ‚Äúthe greatest con job ever.‚Äù He has been scaling back former President Joe Biden‚Äôs green-energy subsidies, doubling down on America‚Äôs world-leading production of oil and gas, and he is ignoring the Bel√©m¬Ýconference.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is making a very different economic bet.

And that is the source of the “improbable glimmer of hope” among some delegates in Brazil.

For while China remains by far the world’s largest emitter of the fossil-fuel gases driving global warming, Mr. Xi’s government has been investing hundreds of billions of dollars in solar and wind energy, storage batteries, and electric vehicles.

That technology is not just for domestic use, though it is already having an effect on emissions in China.

It is also for export, to generate the trade revenue on which China’s economy depends.

Crucially, that has begun giving less-developed countries in the so-called Global South something almost unimaginable a few years ago: a realistic path toward growth that need not rely principally on carbon-emitting fuels.

Pakistan has begun importing large numbers of solar-energy panels. Nearly three-quarters of car buyers in Nepal now choose Chinese electric vehicles. Ethiopia has banned the import of gas-powered cars altogether.

Brazil has moved to persuade China’s giant e-vehicle manufacturers to set up production there.

The sheer pace and scale of the increase in solar- and wind-energy output, with China staking out near-monopoly dominance, and a steep decrease in its cost, have been leading other major developing economies such as India, Nigeria, and even the oil-rich Gulf emirate of Abu Dhabi to embark on solar energy initiatives.

And it has been making a measurable difference.

One example: Worldwide industrial use of fossil fuels has begun to decline, mainly because most of China’s smaller manufacturing plants are shifting to increasingly green sources of energy.

Despite China’s continued use of coal, the most carbon-emitting fuel of all, its total emissions are also on course to decline this year.

Yet only barely. By around 1% – in a country that accounts for one-third of global coal consumption, almost three times as much as the second-largest greenhouse gas emitter, the United States.

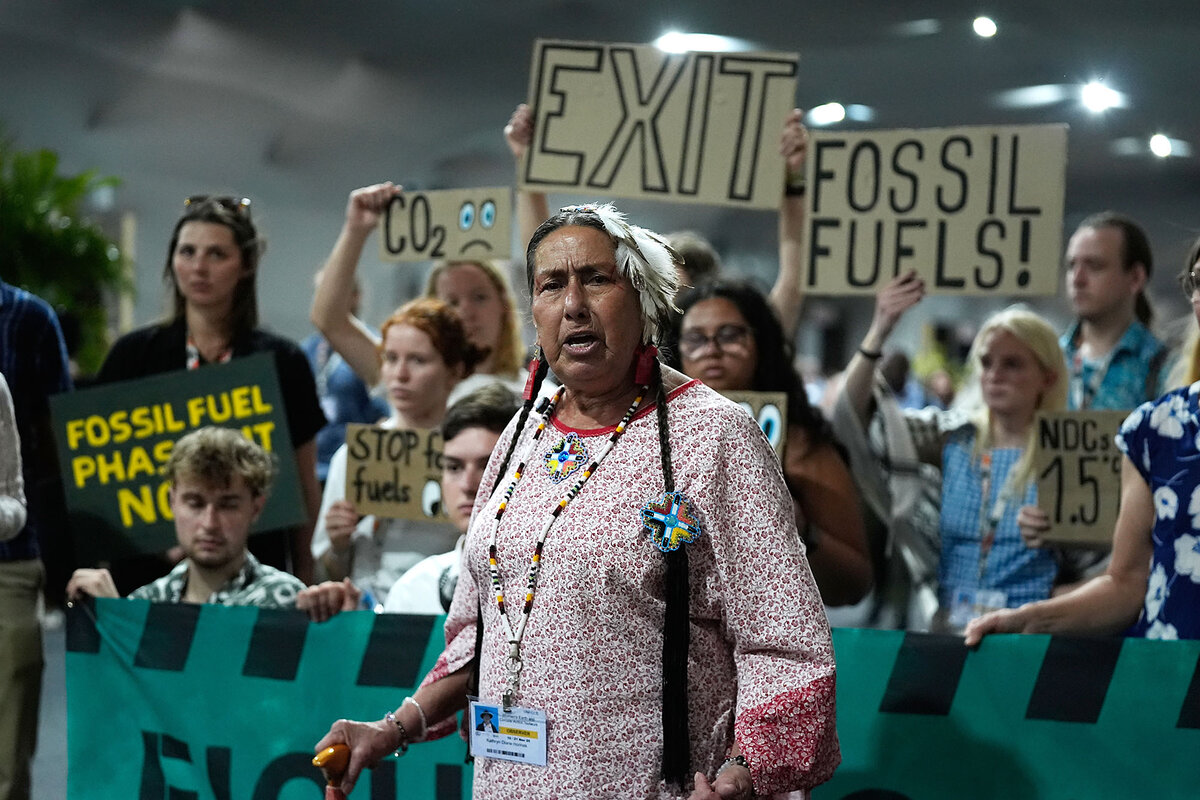

That helps explain the greatest concern voiced by U.N. leaders, international politicians, climate scientists, and activists in Bel√©m¬Ýat the start of their nearly two-week meeting: that even with China‚Äôs move toward green energy, the world might be losing the race to head off the most serious effects of global warming.

Concentrations of carbon gas in the atmosphere increased last year, by the largest amount on record. The temperature of the oceans, key to absorbing carbon, is at a record high. The planet’s temperature over the past three years has been the highest ever recorded.

And even with China’s recalibration, the main tool to reverse that warming trend – a wholesale, worldwide shift away from fossil fuels – still seems a distant prospect.

So, too, appears the likelihood of clawing back enough of the effects of global warming to meet the goal set at a landmark climate conference in Paris 10 years ago – to keep the planet’s temperature no higher than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Significantly, the Paris accord was made possible by the coordinated efforts of the U.S. and China, their last major joint initiative before tensions between the world’s two largest economies began to intensify.

Now, the future of climate change policy could hinge on the rivalry between their dramatically different views of the way forward.

Polling has shown that fewer and fewer people worldwide share Mr. Trump’s belief that climate change is a “fabrication.”

The growing frequency and intensity of so-called extreme events – storms and flooding, heat waves and wildfires – have reinforced concern over its effects.

But Mr. Trump’s argument that other issues, such as economic questions around jobs and immigration, should take precedence does strike a chord among a number of major developed countries, especially in Europe. There, political leaders have been facing new headwinds as they seek to promote green policies.

And it is in the field of potential economic benefits that the climate-change rivalry between the U.S. and China might well be decided.

For Mr. Xi’s investments in clean-energy technology, equipment, and products is not driven mainly by climate science, nor by the impacts of climate change on the weather.

His is an economic calculation.

For China, “going green” is not a cost. It is an opportunity.