Pocketbook polarization: In Hong Kong, you are what you buy

Loading...

| Hong Kong

Being labeled ŌĆ£yellowŌĆØ saved Ivan LamŌĆÖs restaurant business.

The Hong Kong native opened his all-day breakfast nook last year in Causeway Bay, which turned out to be a hotspot for the cityŌĆÖs pro-democracy movement. As the protests began ramping up last summer, Mr. Lam found his restaurant nearly empty, night after night.┬Ā

ŌĆ£Those were the worst days of Hong Kong,ŌĆØ Mr. Lam says. ŌĆ£No one felt like eating out. We had one table each night.ŌĆØ

Why We Wrote This

ItŌĆÖs not news that some Hong Kongers are deeply divided over the protests. But the ŌĆ£yellow economyŌĆØ movement that sprung up this fall highlights how those divides are reshaping relationships, far away from the front lines.

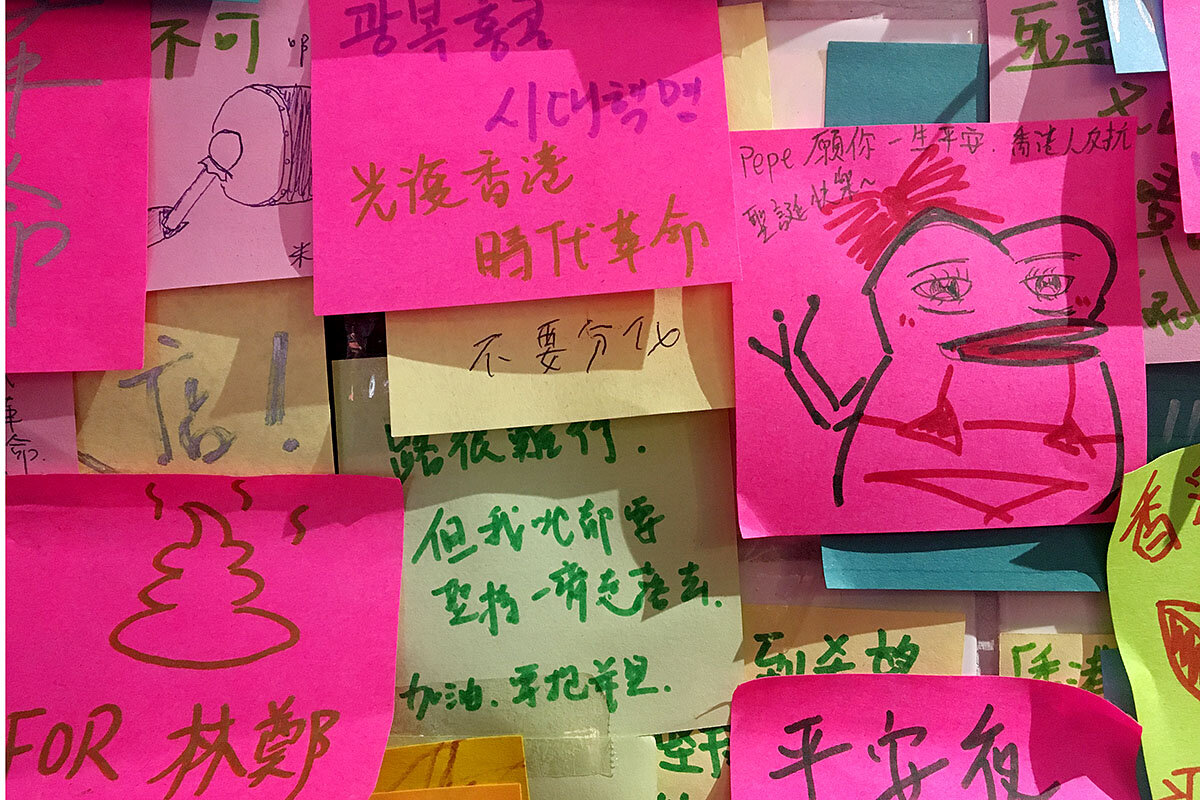

As the months wore on, Mr. Lam allowed protesters to store gas masks and first aid supplies at his restaurant No Boundary, convenient to the front lines. Later, he allowed a permanent Lennon Wall of sticky notes┬ĀŌĆō┬Āoutpourings of expression modeled after the one in Prague┬ĀŌĆō after authorities began taking down public versions throughout the city.

ŌĆ£Eventually, word got out,ŌĆØ says Mr. Lam. He was a pro-democracy supporter┬ĀŌĆō he was ŌĆ£yellow.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Blue,ŌĆØ on the other hand, means pro-police or pro-Hong Kong establishment, seen as aligned with the Chinese central government in Beijing.

In September, mobile apps sprung up identifying retailers by their perceived politics, as the concept of a yellow-circle economy began taking root inside the movement. That allowed people to spend their dollars accordingly, and thatŌĆÖs when the lines for Mr. LamŌĆÖs restaurant began snaking down the street.┬Ā

ŌĆ£It saved us,ŌĆØ says Mr. Lam, who had considered shuttering the business before the yellow circle came to life.

Indeed, as authorities have tightened avenues for legal protest, the yellow circle is one way the movement keeps momentum going. Anecdotally, there has been an economic impact. Ultimately, the yellow economy is symbolic of deeper, long-lasting rifts in society that are separating families, classmates, and others who find themselves on opposite sides.

ŌĆ£The yellow economy is based on personal values,ŌĆØ says Isaac Cheng, vice chairman of the pro-democracy political party Demosisto. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre trying to punish people not supportive to the movement by using money.ŌĆØ

Shades of blue┬Ā

No one can pinpoint the genesis of the concept┬ĀŌĆō much like the protests themselves, which are leaderless and organized largely via anonymous posts.┬Ā

Sometimes, color designations seem clear; other times, less so. One restaurant was deemed blue after waitstaff were overheard commenting that protesters deserved to be ŌĆ£beat upŌĆØ┬ĀŌĆō not necessarily a reflection of the ownersŌĆÖ position.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs sometimes unfair,ŌĆØ admits Hong Kong restaurateur Tim Law, recognizing the challenges of a system that makes things seem black and white, when theyŌĆÖre anything but.

ŌĆ£Not all the blues are so crazy to me,ŌĆØ says Mr. Law, who supports the pro-democracy movement. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a kind of spectrum. I have some friends IŌĆÖd call ŌĆślight blueŌĆÖ because they hate the violence.ŌĆØ

Make no mistake: Mr. LawŌĆÖs restaurant Little Vegas is decidedly yellow. HeŌĆÖs given staff time off to attend protests, sent 10,000 rice bowls to the front line, and allowed Lennon Walls to spring up in his restaurant.

One benefit of the yellow economy, Mr. Law says, is that staff have found new purpose. TheyŌĆÖre united, and customers find reasons other than menu choices and bills to converse with them. ŌĆ£I also feel a lot closer to my staff,ŌĆØ he says, ŌĆ£because before our conversations were more up-and-down. Now itŌĆÖs more horizontal. We talk about things with meaning.ŌĆØ

For some retailers, being labeled blue has hurt business. The cityŌĆÖs $350 billion-strong economy is largely controlled by conglomerates and companies with ties to mainland China. The movement has affected brands such as Bank of China, which experienced an exodus of customers to locally-owned banks.

Also labeled blue is Starbucks, owned and franchised in Hong Kong by MaximŌĆÖs Caterers, whose founding family member called protesters who participated in cyberattacks ŌĆ£.ŌĆØ Several Starbucks stores were vandalized during the height of the violence.

Deepening divides

Whether the financial impact is short-lived or not, whatŌĆÖs clear is that deeper strains increasingly fracturing Hong Kong society are no passing fad.

The older generation, as a rule, tends to prefer things the way they were, while the younger idealists want freedom from Beijing at all costs. There are divisions among the protesters themselves, over methods and the amount of violence employed. Among the student population, native Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese who used to study side by side are finding politics can drive a wedge between them. For some, the mainlanders are hard to separate from their authoritarian government attempting to integrate a fiercely proud city into the mainland.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve become more distant from my mainland friends,ŌĆØ admits Mr. Cheng of Demosisto. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs better we donŌĆÖt connect right now.ŌĆØ

Divisions have opened up within families. ŌĆ£I have friends who can no longer go home,ŌĆØ says protest organizer Ventus Lau. His family worries about him, but he counts himself lucky that they still understand each other. ŌĆ£This is about the cityŌĆÖs future. My family tells me ŌĆśI donŌĆÖt care about the city┬ĀŌĆō I just care about you.ŌĆÖ I can understand that.ŌĆØ

The two sides are so polarized that pro-democracy supporters are afraid to visit beloved shops that happen to be blue, or feel compelled to go in secret.

ItŌĆÖs hard to envision a way out from the new normal. Restaurant owner Mr. Lam, for one, talks about a friend who committed suicide in July, leaving a note that stated ŌĆ£a non-democratically elected government will not respond to our┬Ādemands.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The only way to heal this type of trauma is by getting what we want,ŌĆØ insists Mr. Lam, his face darkening despite the light emanating from his restaurant. ŌĆ£Freedom, democracy, and the five demands.ŌĆØ

Trying to shop neutral

Back on the street, Hong Kong homemaker Bert Liu donned a black face mask, signifying protest support, while waiting in line at Lung Mun Caf├®. ŌĆ£I eat out five times a week at yellow shops,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£I need to play my part.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Others, however, are not moved by the yellow economy. Sharon Wong finished up lunch at the blue Glee Caf├® when she stopped to talk to the Monitor.

ŌĆ£I had no idea it was labeled blue,ŌĆØ says Ms. Wong, a native Hong Konger who works as a physiotherapist. ŌĆ£I have no stance on any colors. I just want to have a great lunch.ŌĆØ

Yet that kind of stated indifference is also a position, insist some protesters. They label it with a different kind of moniker┬ĀŌĆō an animal, not a color.

They liken them to Hong Kong pigs. ŌĆ£They just want a normal life,ŌĆØ says Mr. Lau, who last week learned he faces an incitement charge, which could carry a six-year prison term. They ŌĆ£just want to eat and sleep.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£But this┬ĀŌĆō this is our cityŌĆÖs future.ŌĆØ