An election in Nicaragua that could further dim democracy

Loading...

| Mexico City

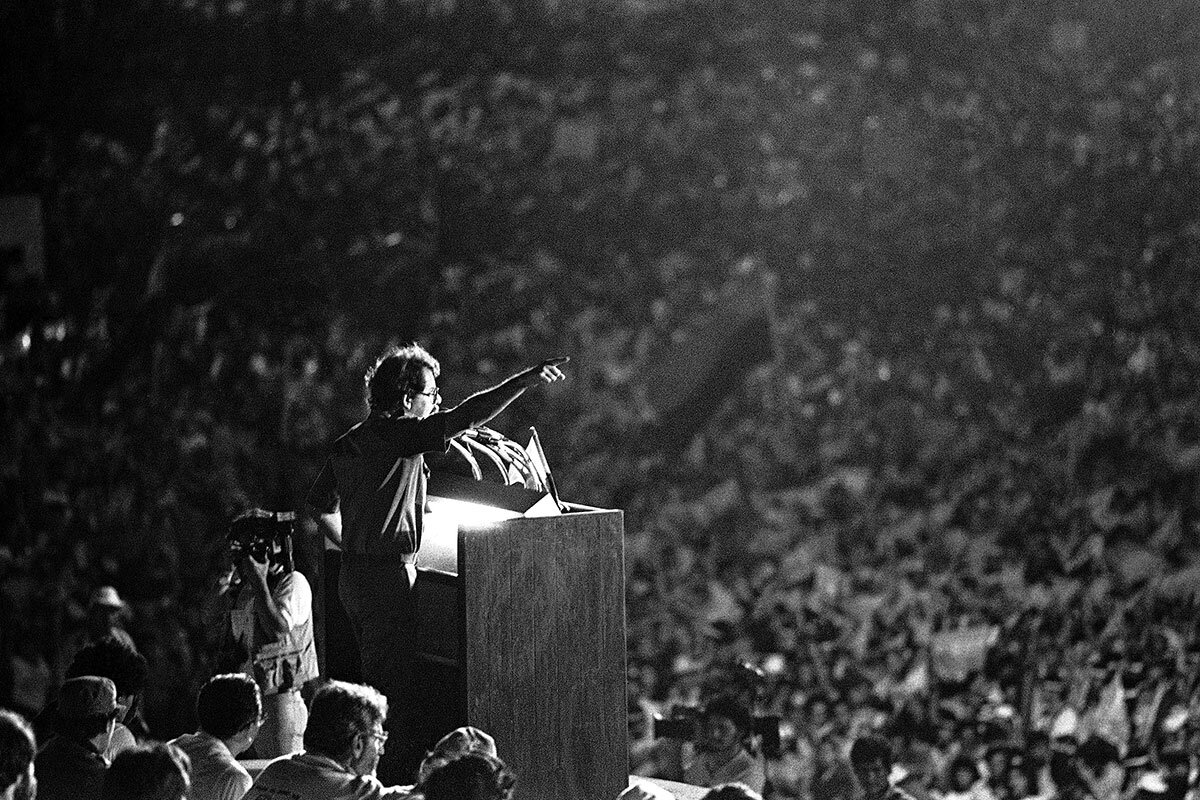

Under the wing of Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua buzzed with revolutionary promise at the height of the Cold War.

The former guerrilla fighter��and his Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) toppled the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, and won presidential elections five years later – bringing democracy to the Central American nation. At the time, foreign journalists flocked to Managua to cover the historic transition.

Forty years later, Mr. Ortega leads Nicaraguans to the polls once again. But there is no international press corps here now. There are no rivals either.

Why We Wrote This

Like so much else, the politics of Nicaragua can feel like déjà vu. In many ways Daniel Ortega has become the dictator he once toppled – and he’s put the international community on edge again.

Even before Nicaraguans vote Nov. 7, the results are already clear: Mr. Ortega is running essentially uncontested for his fourth consecutive presidential term after an unprecedented crackdown on opposition candidates and press freedom this summer.

This race marks a watershed moment for the country, not because of the outcome but for where Nicaragua goes next. The opposition and international community face the task of reestablishing democracy here, and the stakes are high. Just as the Sandinistas inspired a generation of revolutionary leaders in the 1980s, today’s FSLN could embolden authoritarianism in the region.

“Unlevel playing fields are common in Latin America, but still not to this level,” says Tiziano Breda, Central America analyst for the International Crisis Group. “There is not even a playing field.”

“If there is no robust and coordinated response,” he adds, “it will set a dangerous precedent for the region where other authoritarian wannabes are not lacking.”

“Nothing Sandinista left”

Once a beacon for the left, Mr. Ortega has moved far from those ideals. He once vowed to free Nicaragua from the shackles of a corrupt dynasty that funded its lavish lifestyle at the expense of poor Nicaraguans. Now, he lives as lavishly and has appointed his family to top leadership posts, including his wife, Rosario Murillo, who is vice president. Nicaragua remains the nation in the Western Hemisphere.

Since first returning to power in 2006 elections, Mr. Ortega has reformed the constitution to allow reelection and stacked the judicial system with loyalists. When he faced a mass anti-government protest movement��in 2018, he sent police to violently repress it. International human rights groups call that crackdown a crime against humanity.��

It was also a betrayal of the 1979 revolution, says Gioconda Belli, a prominent Nicaraguan poet who worked clandestinely for the Sandinistas before the revolution and supported them enthusiastically in the early days of their rule. “It was an anti-dictatorial movement,” she points out. “We fought against a 45-year-old dictatorship, so to go back to dictatorship [means] there is nothing Sandinista left.”

Despite ongoing repression, a coalition of opposition organizations came together in 2018 to form a front they named Blue��&��White National Unity��(UNAB), hoping to defeat Mr. Ortega and return Nicaragua to democratic rule.

“We saw a small window of opportunity for Nicaraguan citizens to elect new authorities, even in such adverse conditions,” says Alexa Zamora, a member of the political council of UNAB who is now in exile. But the window quickly shut on them.

In June, the government placed under house arrest leading rival Cristiana Chamorro – daughter of former President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, who defeated Mr. Ortega in 1990 elections – on charges of money laundering, which she denies. Within weeks, the remaining six contenders were imprisoned under a law passed in December 2020 criminalizing “traitors.” That has left just five other candidates – all considered Ortega loyalists – on the ballot.

An October CID Gallup poll showed only 19% of Nicaraguans planned to vote for Mr. Ortega, compared with 65% who supported an imprisoned opposition candidate.

A chilling effect

Mr. Ortega’s crackdown reaches beyond the political world. As of Nov. 4, the government had arrested 39 people, including Francisco Aguirre-Sacasa, former Nicaraguan ambassador to the United States who spoke critically of the government after the 2018 crisis but toned down his��comments before elections.��“My father’s retired from politics,” his daughter Georgie Aguirre-Sacasa says. “He’s a horse farmer and a grandfather. He is not a spy or whatever they are claiming he is.”

The Ortega-Murillo government has justified its actions as necessary to defend the country against “foreign interference.” In a June speech, Mr. Ortega condemned “false narratives espoused by right-wing media and U.S.-funded ‘opposition figures.’”

In July, Nicaragua’s Supreme Electoral Council announced it would not allow electoral observers. At least a dozen foreign reporters have been denied entry or never received a response to a request for a journalist’s visa, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The government wants an “information blackout,” says Cindy Regidor, a Nicaraguan journalist with independent media outlet Confidencial who is now living in Costa Rica. Police harass and confiscate equipment from journalists working in the field, and public prosecutors have called journalists in for questioning so as to intimidate them, she says. “What exists in Nicaragua is a regime that now uses judicial persecution against anyone they consider an adversary, including journalists.”��

That tactic has had a chilling effect on political debate. “There’s a lot of fear in Nicaragua – fear of repression, of arbitrary detentions, and of criminal charges for crimes against national integrity,” says a UNAB member who asked not to be identified to ensure their security.��

A path forward

Ortega’s “virtual beheading of any slight electoral challenge” is incomparable to any elections in Latin America since the region’s transition to democracy after military dictatorships in the 1980s, says Mr. Breda. Even in Venezuela some participation by rival candidates has been allowed; the opposition won control of Congress in 2015.

And that’s why the international community must mobilize, he says.

With the election outcome certain, UNAB has launched a campaign called “Let’s Stay at Home” urging Nicaraguans to refrain from the Nov. 7 vote and calling on the international community to reject the outcome and demand another race.

The actions of the regional Organization of American States, which issued a resolution on Oct. 20 calling for the release of political prisoners and respect for free elections, will be crucial to set the tone of the international response, UNAB says.

The U.S. Senate this week passed the Renacer Act,��which calls for restrictions on the Nicaraguan��government’s access to international funding and sanctions on officials involved in attacks on��democracy and human rights abuses.��Mr. Breda says the international community must coordinate condemnations and sanctions after the elections.

UNAB leaders say they hope to establish dialogue with the government. But first, they insist that all political prisoners must be freed.

They know reestablishing democracy will likely be a yearslong process – and they aim for it to be peaceful, unlike the armed resistance Mr. Ortega once waged, says Ms. Zamora.

“Nicaraguan citizens have chosen the civic and pacific route,” she says, “as the only route out of this socioeconomic crisis.”

We are withholding the byline on this article in order to ensure the author’s security.��