Has guaranteed basic income’s time arrived? Canada may find out.

Loading...

| Hamilton, Ontario

Jessie Golem knows the stigma of poverty. She’s been called a leech and parasite. She’s heard more times than she can count, “Go get a job.”

In fact, she always had multiple jobs. But piano lessons, gigs in dog walking, and a budding photography business – a 60-to-80-hour weekly hustle – left her just enough to pay her rent in Hamilton.

It wasn’t until she became part of a pilot program in Ontario, receiving a basic income supplement of $1,400 a month, that her working life finally came together. “It was really awesome watching my photography business grow,” she says. “I drew up a whole business plan and had a financial projection that I would only have needed to be on the basic income pilot for two of the three years.”

Why We Wrote This

As people’s livelihoods have been thrown into upheaval amid the pandemic, public desire for a stronger safety net has increased globally. Has the time come for a government-supplied basic income?

That pilot ended after its first year with a change in provincial government in 2018 – frustrating the centuries-old idea of a guaranteed basic wage that has never taken off beyond limited experiments in the last 50 years. But now that millions of Canadians have experienced what it’s like to lose a job or had hours cut back with no recourse, now that citizens around the world have only been able to find a way forward with a government check, an idea that once lived on the fringe has become more mainstream.

Driving the discussion in recent years are technological disruption and artificial intelligence, as well as structural economic systems behind a global gig economy. The idea faces huge hurdles – from cost to societal disdain for “getting something for nothing” – but the pandemic has born a new group that understands intimately how fragile economic security can be.

“People in the middle class who thought they were pretty secure, all of a sudden discovered they’re not,” says Sheila Regehr, chairperson for the Basic Income Canada Network.

A call for basic income

Since March, the idea in Canada has been formally endorsed by many groups, , when unions have traditionally worried streamlining welfare into a basic income program could imply a loss of public jobs and services, Ms. Regehr says.

A group of Liberal lawmakers called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in a minority government with the leftist New Democrats, to make basic income a top policy resolution at the party’s November convention. Many are awaiting the government’s throne speech Wednesday to open a new session of Parliament for hints of the country’s future social safety net.

Basic income has been piloted from Finland to Stockton, California. Former American presidential contender Andrew Yang proposed a monthly $1,000 check to all Americans. That’s universal basic income (UBI). In Canada, the pilot project acts as a supplement, something akin to a policy already in place for seniors to guarantee none will fall below the poverty line. The idea remains highly contentious. One news item about it drew more than 17,500 comments.

But attitudes are shifting, here and abroad. In a poll carried out by Public Square Research in May, 62% of respondents in Canada said they’d support a guaranteed income program paid for by the government. A majority is in favor , where Germany and Spain are attempting new policies.

Even in the U.S., where work is “imbued with an almost religious significance,” says Matt Zwolinski, director of the Center for Ethics, Economics and Public Policy at the University of San Diego, the issue in municipalities across the country. He says governments have gotten more comfortable in how quickly they can issue payments, and what a lifeline they’ve been during the pandemic. And society has gotten more comfortable with them too.

A conservative case for basic income

A basic income has long been viewed as a left-wing, utopian ideal, but throughout history support has also come from the right, including famously the economist Milton Friedman. And now the pandemic also added a moral imperative, especially as it’s so heavily hit minorities, women, and the poor, says Mr. Zwolinski.

“There’s an idea behind a basic income guarantee … that we ought to have some kind of floor below which nobody is allowed to sink,” he says. “And that, I think, is a really appealing idea that transcends a lot of the standard political division between left and right, because it’s not a radically egalitarian proposal. … It’s saying regardless of how rich we allow people to become in society, we ought to make sure that everybody has at least enough to get by.”

Here in Canada, one of the staunchest supporters of a basic income is Hugh Segal, a former Conservative senator who designed the Ontario pilot that Ms. Golem participated in. He points to a parliamentary budget officer report that estimated the cost of the program would be $76 billion but would be eventually be offset by savings of some $30 billion in current welfare programs.

Mr. Segal argues that any program would be offset by billions in administrative savings, while paying a dignified wage without the disincentives to work built into current welfare policies. “And that’s without counting any of the savings we would get in the healthcare system, the penal system, and elsewhere by reducing the pathologies of poverty.”

With the rise of artificial intelligence, basic income has been touted as a modern response to a new economy, why people like Elon Musk support it. James Collura, a recipient in the Ontario pilot, studied economics at McMaster University in Hamilton and got a part-time job as a bank teller. He quickly learned that the better he accomplished his job to move clients online, the more his job became obsolete.

A guaranteed income gave him the space to reflect. He changed jobs – even though the new one had no benefits – to a flotation therapy and wellness center. That center had to close its doors when the pandemic hit. He then qualified for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), or what he calls “UBI round two,” which he has used to take an even more spiritual path. Today he lives in a monastic Buddhist community in Hamilton, where he is working on a permaculture food forest project. He says he feels as stable as anyone could. “And I think right now, we need people to feel safe and secure so that we can actually work together and not feel so anxious and afraid.”

“A small minority will always game the system”

Mr. Segal bristles at criticism that recipients “sit on the couch eating bonbons.” In , which included 4,000 participants in Hamilton, Lindsay, and Thunder Bay, a basic income motivated the vast majority to find a better-paying job. Participants said they felt healthier, more mentally secure, and freer from addictions like alcohol. Similar results were found in a larger project from Manitoba in the 1970s. A small minority will always game the system, Mr. Segal says. The same percentage, he adds, will game Wall Street.

“We all have an aversion to the notion that you get something for nothing. But we have a whole series of what I would call ‘free money processes’ now in the system,” he says, like taxation rates in industrialized countries that are lower for companies to implement new technologies than hire employees.

Mr. Zwolinski says there have been limits to studies on workforce implications because no experiment has lasted long enough. “If I tell you that I’m going to give you a thousand dollars a month for the next 12 months and then I’m going to stop, you’re not going to retire,” he says. “But if I tell you I’m going to do this for the rest of your life, that might very well have a more profound impact on your participation in the labor market.”

Maria Anyusheda, an environmental science graduate whose daughter toddles around a park on a recent day in Hamilton, says she could use the support. With a basic income she would start looking for a job. Yet she wonders if that’s the most targeted approach to reduce inequalities. “To help the greatest number of women, they should provide available and affordable day care,” she says. (Amid the pandemic, women’s participation in the Canadian workforce fell to its lowest level in three decades, according to a July Royal Bank of Canada study.)

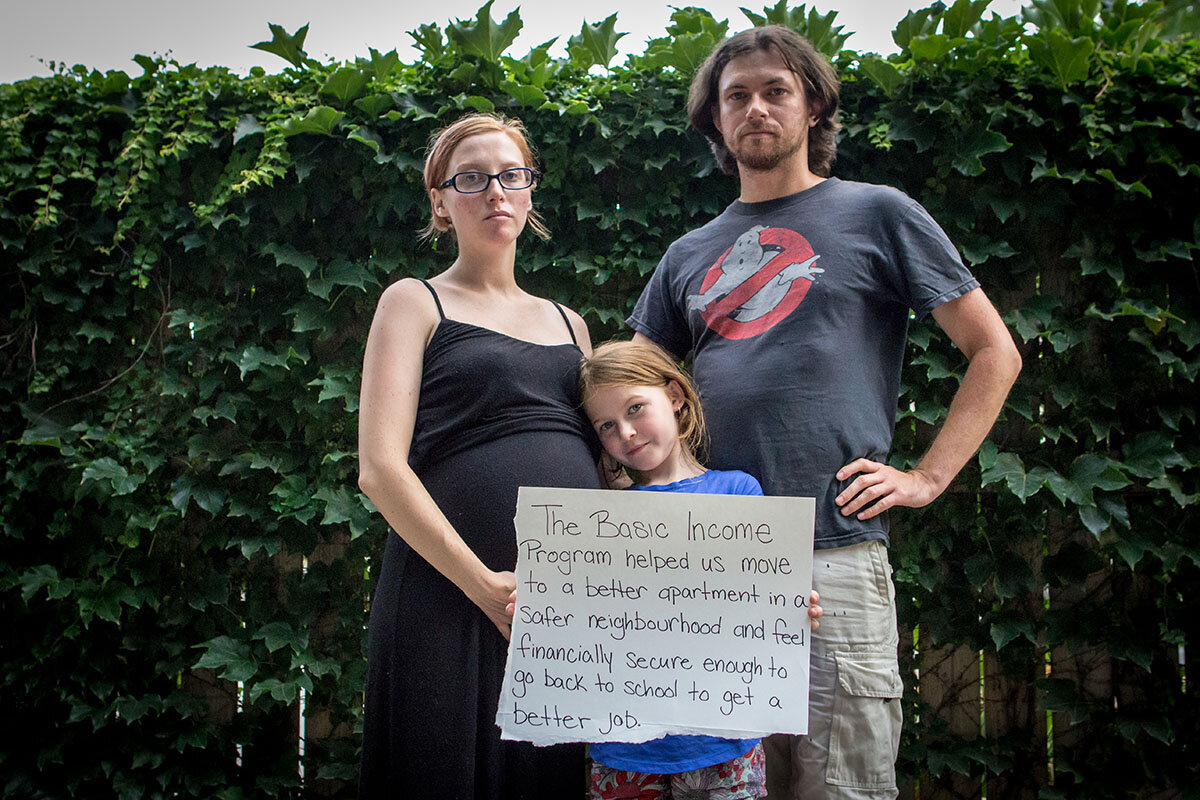

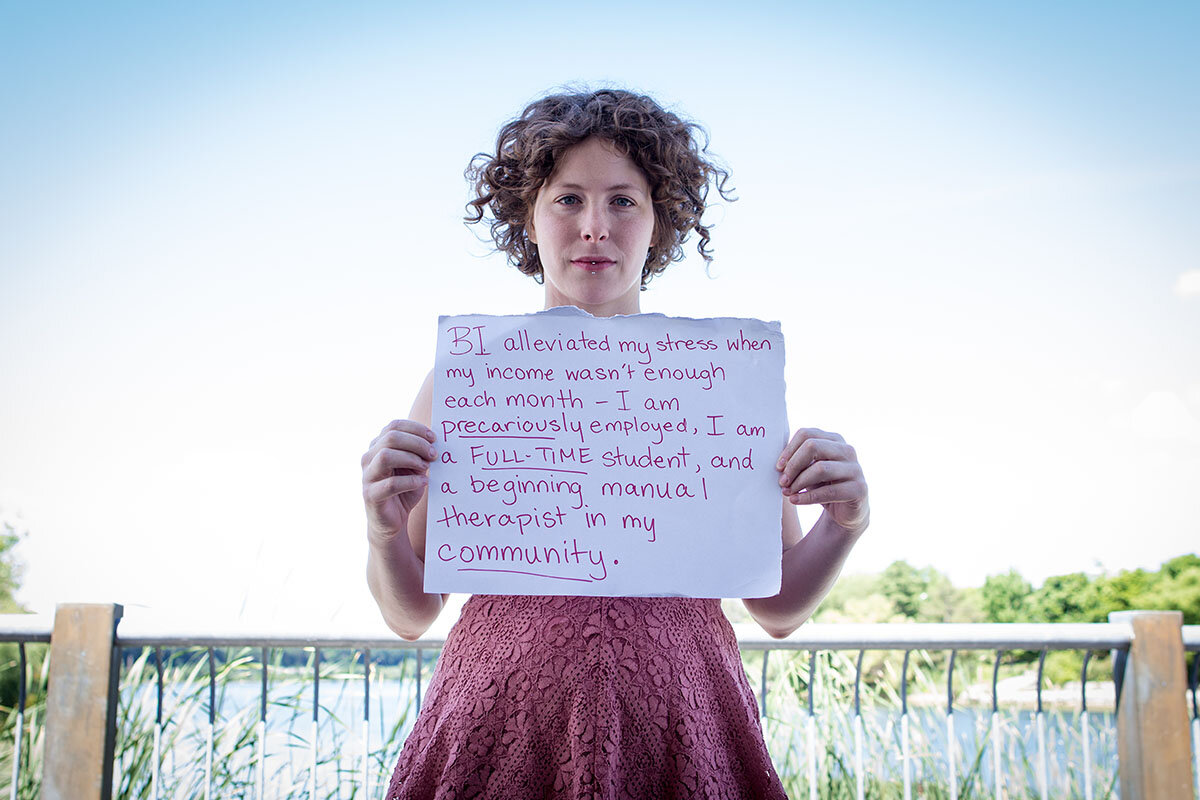

Ms. Golem has tried to humanize the idea. When the Ontario pilot ended, she created a photography exhibit called “Humans of Basic Income” that captures the stories behind the stipends. Now the pandemic has made poverty even more relatable, she says, as she nervously awaits Mr. Trudeau’s plans on basic income. “When the economy crashed, it highlighted that we’re all way more fragile than we think we are.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.