Why Guatemala’s 180 on corruption matters for Central America

Loading...

| Mexico City

A constitutional and political crisis has been averted – temporarily, at least – in Guatemala this week, after the Constitutional Court ruled that President Jimmy Morales could not unilaterally expel an international investigative body focused on fighting corruption.

Mr. Morales previously has attempted to muzzle CICIG, as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala is known. And observers say the court’s ruling isn’t likely to halt government attempts to play down the outsized role of corruption here, particularly with presidential elections on the horizon. The United Nations withdrew the commission members this week after the government’s refusal to guarantee their security.

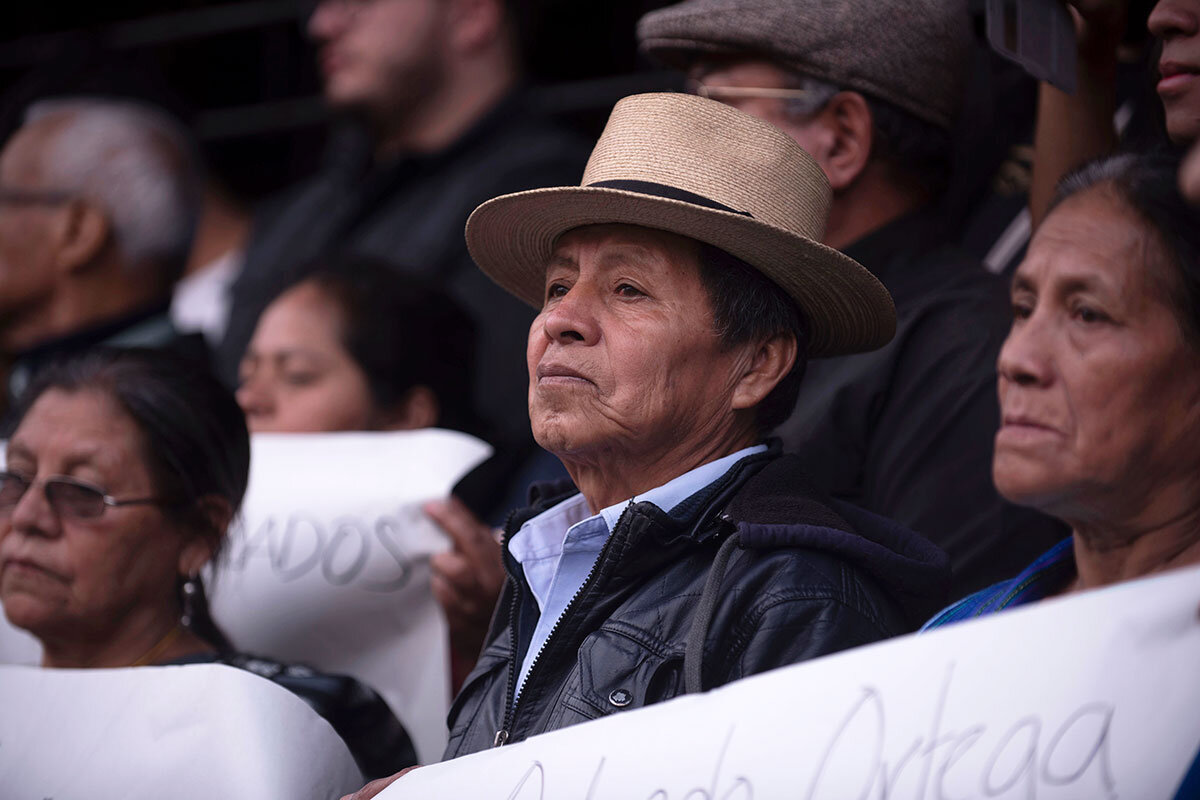

It wasn’t long ago that Guatemala made a name for itself by prioritizing the fight against impunity and corruption. In 2015, tens of thousands of Guatemalans took to the streets for weeks to demand resignations from the then-president and vice president over a bribery scandal. And Morales was elected to the top office in a campaign where he painted himself as “Not corrupt, not a thief.” In 2016, Morales renewed CICIG’s mandate, allowing it to continue investigating some of the most high-profile corruption cases and criminal networks in the country, working alongside the public prosecutor’s office. But Guatemala’s dedication to rooting out corruption began to sour when cases implicating the business community, former officials, and Morales himself – for illegal campaign financing – started to emerge.

Why We Wrote This

A president vowing to clean up corruption has changed his tune since he came under scrutiny. Whether the country’s other institutions allow investigators to stay the course could reverberate beyond its borders.

Now lawmakers are threatening to strip the immunity of judges on the very court that halted CICIG’s banishment this week, in an effort to try them for interfering with foreign policy decisions.

Guatemala’s about-face on corruption is telling, both on a national and regional level. In recent years, governments in Central America from Honduras to Nicaragua to Guatemala have flouted decades of both lip service and concrete steps toward strengthening democratic institutions. International players like the United States are scaling back their role holding regional leaders accountable for actions from electoral fraud to repression of public protest, and Central American governments are increasingly eyeing their neighbors, taking notes on how far they can go in eroding democratic institutions.

“What’s happening in Guatemala and how this resolves itself – it’s not just important for Guatemala, but for the region,” says Adriana Beltrán, director of citizen security at the Washington Office on Latin America, a D.C.-based human rights organization. “What’s at stake here is not just whether CICIG stays or not; it’s the future of the rule of law and democracy, and countries not too far away, like Honduras, are watching closely.”

Look and learn

On Monday, Morales said Guatemala was unilaterally withdrawing from the United Nations-backed CICIG, with his foreign minister ordering its staff to leave the country within 24 hours.

Defending his government’s decision at a press conference, Morales was joined by individuals who say they were falsely accused by CICIG investigations. Morales said the body "violated the human rights of Guatemalan citizens and foreigners residing in the country.”

CICIG was created in 2006 to carry out independent investigations on corruption, genocide, and drug trafficking, and its work has implicated three former presidents. The body has been the envy of many citizens in the region seeking an end to the corruption and impunity that plague so many governments here, with 2015 public protests in Honduras over corruption in the social security institute leading to the creation of a similar independent anti-corruption body backed by the Organization of American States (OAS) and known as the Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MICCIH).

But the further investigations have reached, the more enemies CICIG has earned, with critics – now including former supporters like the business community – saying the group is politically motivated and is violating Guatemala’s sovereignty.

This isn’t “just about the president. It’s about the president and his allies,” says Ms. Beltrán, noting that CICIG has been “extremely successful” at shining a light on the extent of corruption in the country, which “extends to every government institution and implicates members of the military and private sector.”

International attention on Guatemala this week has been unflattering, casting the president’s actions as meddling with a body that has roughly, according to recent surveys. But it’s a cost that politicians feel is worth paying to undermine the anti-corruption battle at home, says Renzo Rosal, a Guatemalan political analyst and columnist.

“The risk factors aren’t high,” Mr. Rosal says. “There aren’t big public protests like we saw in 2015, the US is far less interested in Guatemala, and the public statements made by US lawmakers don’t have much teeth,” he says. “The government feels the risks are under control, and for that reason they’ll continue bulldozing ahead,” possibly stacking the Constitutional Court with allies – or doing away with the body completely.

“I think everyone in the region is watching each other,” says Rosal, citing how Honduras worked around a constitutional ban on reelection, allowing sitting president Juan Orlando Hernandez to win again in 2017 in an election deemed “irregular” by the OAS (which called for a). Guatemala also has a constitutional ban on reelection, which Rosal doesn’t rule out as something the sitting government may try to change.

“Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala – they’re all watching and emulating each other, planting seeds of doubt in the public and creating powerful waves of dubious change in the region.”