Why an Argentine leader seeks to break the pull of populism

Loading...

| BUENOS AIRES

Young Andrûˋs Watle has only been around for about three decades ã and yet thatãs long enough to have known the economic ups and downs of Argentinaãs legendary populist governance.

ãIt seems great when youãre living the good times of el populismo, with services practically given away and a feeling that weãre a wealthy country,ã says Mr. Watle, a Buenos Aires travel agent.

ãBut inevitably comes the fall to the not-so-good times, and that feels less good, and it hurts a lot of people,ã he says. ãItãs a pattern we need to break.ã

Why We Wrote This

President Macri promised to make Argentina a ãnormalã country, far removed from the populist boom-and-bust economic cycles of the past. But populism's pull may be stronger than he bargained for.

Breaking the pattern of the boom-and-bust economic cycles that have defined Argentinaãs economy for decades was a central objective of Argentine President Mauricio Macri when he took office in 2015.

Mr. Macriãs winning campaign pledge: to make Argentina a ãnormalã country, permanently off the populist roller-coaster.

In Argentina, populismo is historically associated with the left: leaders who are charismatic and pledge to serve ãthe peopleã over national elites, and rely on widespread public spending and subsidies. Theyãve played a key part in perpetuating a boomerang economy. A populist will typically spend widely on social programming, and when the coffers are empty and a new, typically opposition leader is elected, the nation takes on austerity measures.

Macri inherited an economy that was careening toward default. His predecessor, Cristina FernûÀndez de Kirchner, used the proceeds of the recent commodities boom to heavily subsidize gasoline and provide electricity that was practically free.

For many economists, especially free-market liberals, Macriãs task was nothing short of halting Argentinaãs slide under the Kirchners to something approaching the economic collapse of Venezuela.

But three years later, Macri is finding that weaning ãthe peopleã off the milk of populism is not easy ã perhaps all the more so in a country where the populist tradition extends back to the post-WWII boom years of Juan and Eva Perû°n.

To stave off default, Macri this year negotiated a $57 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. But the loan came with strings attached: cuts in spending, slashed subsidies, cutbacks in the pension programs that had been expanded by Kirchner and her predecessor in office, her late husband Nûˋstor Kirchner.

As electricity bills and gas prices have soared, and unemployment rates and small-business bankruptcies have risen, Macriãs popularity and prospects for re-election next fall have plummeted.

ãThis is a country that after so many years of populism has become used to the government handing out more all the time,ã says Juan LuûÙs Bour, chief economist at FIEL, the Foundation for Latin American Economic Studies, in Bueno Aires. ãArgentines basically understood this system was not sustainable ã which is one reason Macri won,ã he says. ãBut to get to ãnormalã the government has had to break some eggs, and that kind of change is going to hurt a lot of people.ã

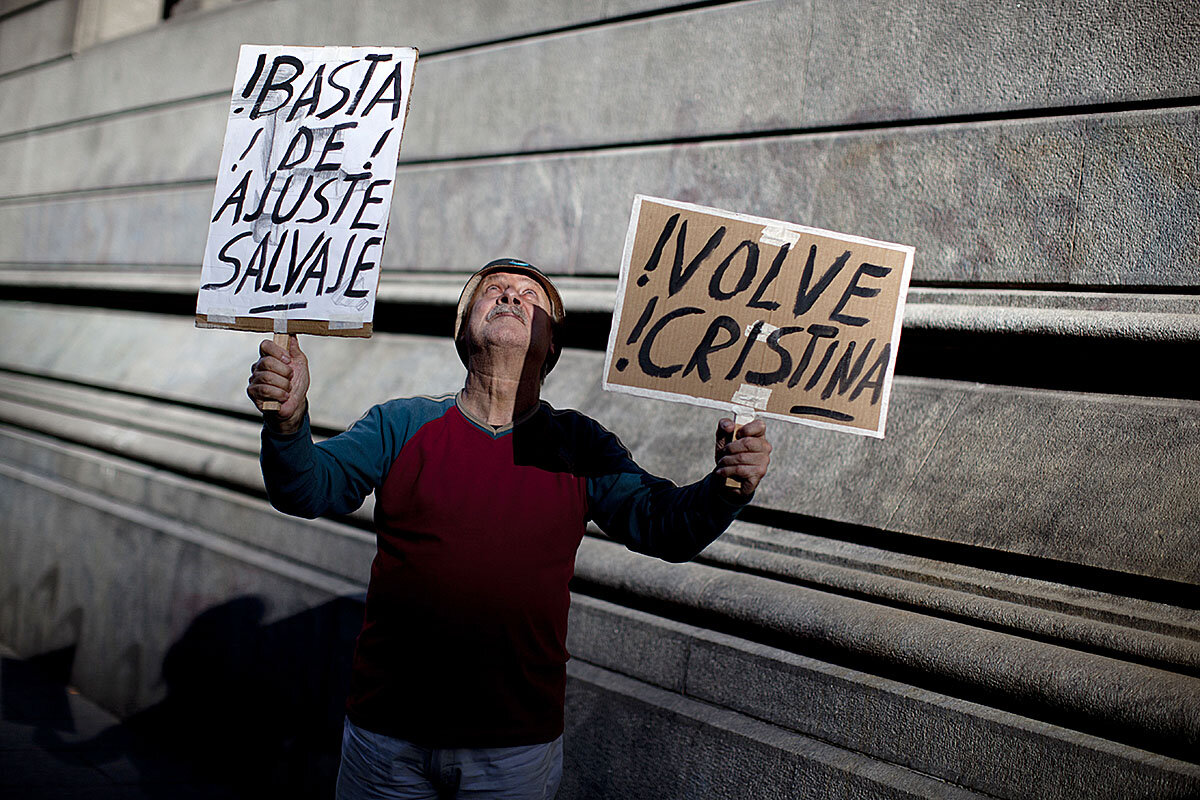

As Macriãs fortunes have crashed, prospects for the return to power of Kirchner ã and for yet another swing to the populist left ã have risen.

ãThe popular thinking out there is, ãMacri tried to move us away from populism ã and look where it got us, to even higher debt, higher and rising unemployment, and more difficult living conditions,ã ã says MatûÙas Carugati, chief economist at Management & Fit, a Buenos Aires consulting and public opinion firm. ãPeople tend to remember the good times of populism, but no so much the bad.ã

ãWe can't eliminate it in four yearsã

Polls show Macri retaining support of about a quarter of the electorate. They show Kirchner with similar levels of support. That leaves a huge slice of the population dissatisfied with both options ã and seemingly open to some third candidate, yet to emerge.

Noting that many economists expect the governmentãs tough adjustment measures to begin yielding positive results next year, Mr. Carugati says an economic recovery that is perceptible to the public might not come soon enough to boost Macriãs electoral fortunes.

Global conditions havenãt helped, Carugati says. Macri banked on a recovery through opening up the country to the world ã just as the global trend moved to heightened protectionism and less enthusiasm for trade accords.

Pointing to a shantytown that has sprung up within eyesight of the sleek high-rise where he works, Carugati says South American migrants ã most recently from Venezuela ã have streamed in, exacerbating conditions for poor Argentines.

But perhaps most important is that one presidential term may not be enough to change a national mindset, he says.

ãIf itãs a cultural thing that we Argentines are fond of populism, maybe the reality is that we canãt eliminate it in four years.ã

Carugati says other Latin American countries, including next-door neighbors Uruguay, Chile, and Peru, have moved away from populist pasts, ãso we know itãs possible.ã

Yet, not all populist models in the region are alike. In Chile, for example, populism was carried out by a brutal military dictatorship. No one emulates that today, making it easier to banish the approach.

ãA populist 'habitã?

Itãs not difficult to find unhappiness with Macriãs project on the streets. Alfonso Andrade, a produce vendor in the cityãs San Telmo neighborhood, says electricity price hikes alone ã he claims to have been hit by a rise of 4,000 percent in his bills ã could do him in. ãAt this rate I could lose my business,ã he says.

But thatãs just in the center of the capital, which by most measures is far better off than the rest of the country.

ãWhere we are right now, this is New York, you wouldnãt know weãre in a stagnant economy,ã says MartûÙn Ortiz, referring to the upscale section of Buenos Aires where he teaches English for a living. ãBut come out to where I live, and it starts to be more like Detroit,ã he says, referring to where he lives about 20 miles south of the capital.

Mr. Ortiz says Macri hasnãt been radical enough in forcing change in Argentina.

ãHe started out in the right direction,ã he says. But, heãs ãpulling back from what he promised in the interest of getting re-elected.ã

One reason for Macriãs retreat is that in order to change the country, he has had to challenge how Argentines see themselves, some social observers say ã and that has not always gone down well.

Take the example of beef. For much of the 20th century, Argentina was one of the worldãs top beef exporters. But the emphasis on exports made it increasingly expensive at home.

Mr. Bour of FIEL says the Kirchners saw imposing high taxes on beef exports as a way to kill two birds with one stone ã fill government coffers to help pay for subsidies, and make beef a staple of the Argentine dinner plate again. Argentina slumped from its top-tier ranking among world meat exporters to 11thô or 12thô place, Bour says.

Last month Macri announced Argentinaãs re-entry into the US meat market during President Trumpãs visit for the Group of 20 industrialized countriesô summit. But higher domestic prices have once again led to public grumbling.

Bour says that older Argentines are among the biggest supporters of a return to populism ã in part because Kirchner made a government pension the right of everyone, whether they contributed to the system or not.

But perhaps more surprising is the strong youth support for Kirchner in the polls.

ãThe younger people grew up with the Kirchners, and many of them associate those years with good times,ã says Carugati. Mrs. Kirchnerãs time in office is also associated with an era of idealistic themes like human rights and regional solidarity.

Compared to that, the idea ãof making Argentina a ãnormal countryã isnãt as attractive,ã he says.

ãBut Iãm a young person too,ã says Watle, the travel agent. ãI think there are a lot of others like me who believe that as difficult as it might be, we have to break the populist habit.ã