Their parties were fierce rivals. Now they rule South Africa together.

Loading...

| Johannesburg

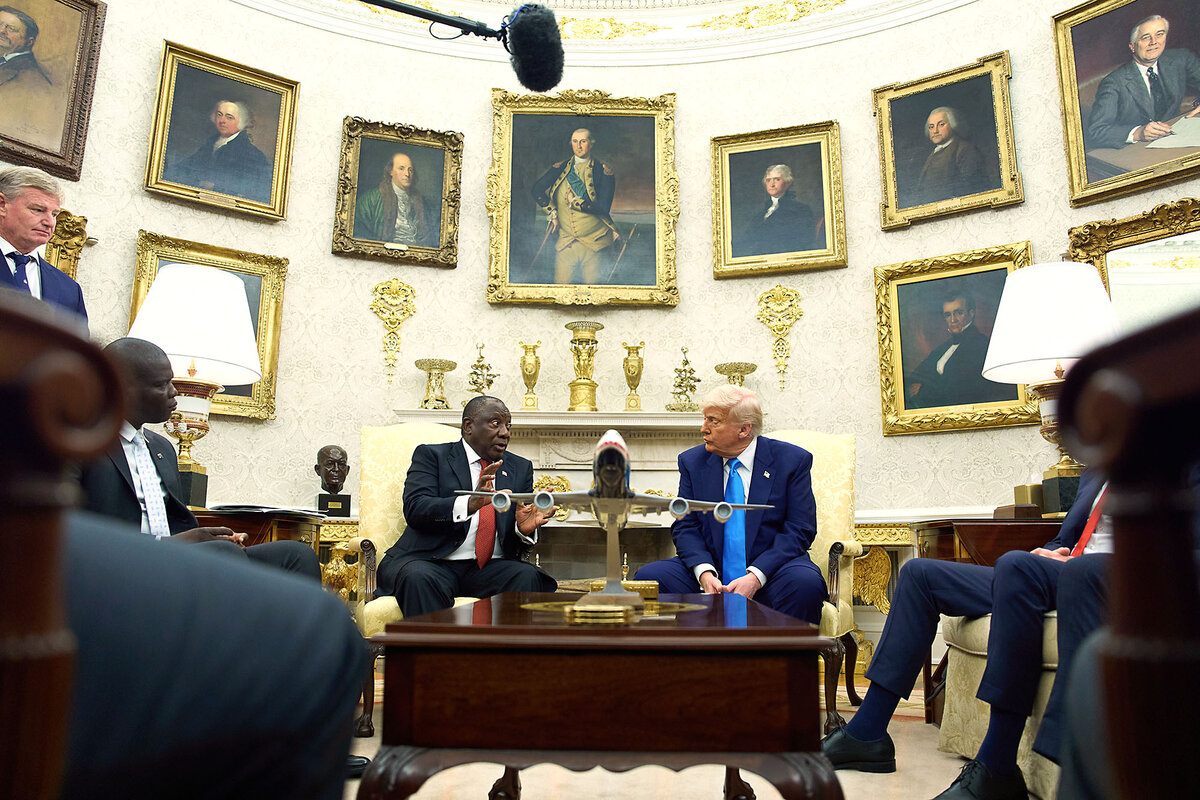

The Oval Office tête-à-tête between President Donald Trump and his South African counterpart, Cyril Ramaphosa, was off to a rocky start.

That morning in May, Mr. Trump dimmed the lights. Then a video began to play, showing a populist South African politician named Julius Malema singing an anti-apartheid song whose chorus translates to, “Kill the white farmer.”

The video was proof, Mr. Trump explained, that white South Africans feared for their lives.

Why We Wrote This

When South Africa’s two biggest parties, which were historically rivals, formed a coalition government last year, few thought it would last. But it did, marking a new era of solidarity and compromise in the country’s politics.

Mr. Ramaphosa shot back. “That is not government policy,” he said. Then another voice chimed in.

To understand race relations in South Africa, Mr. Trump shouldn’t pay attention to Mr. Malema’s incendiary remarks, explained the country’s minister of agriculture, John Steenhuisen, who is white. Instead, he should look at the multiracial coalition government ruling the country for the past year.

After more than two decades of bitter rivalry, Mr. Steenhuisen’s party and Mr. Ramaphosa’s had “decided to join hands,” he continued, in part to keep populists like Mr. Malema out of government.

It might not have been proof enough for Mr. Trump. But in South Africa, the two leaders’ reaction to their Oval Office ambush served as a remarkable public display of a new era in the country’s politics, one marked by solidarity and compromise.

Until recently, few thought such a moment was possible.

Unlikely bedfellows

Mr. Ramaphosa and Mr. Steenhuisen’s uneasy alliance began last June, after the president’s African National Congress (ANC) lost its majority in the polls for the first time since the end of white minority rule three decades ago. Disillusioned voters punished the party for years of corruption scandals, service delivery failure, and high unemployment.

The ANC won just 40% of the vote, forcing it into a coalition with Mr. Steenhuisen’s Democratic Alliance (DA), which had long led the opposition.

The two parties were unlikely bedfellows, to say the least. Not only did they differ on key policy points; they occupied very different roles in the country’s imagination.

The center-left ANC was the storied party of global icon Nelson Mandela, known for liberating Black South Africans from apartheid. The center-right DA, meanwhile, struggled to shed its image as the country’s “white party” because of its mostly white leadership.

Most pundits predicted their precarious coalition, dubbed a Government of National Unity (GNU), wouldn’t last a month. Cartoonists and commentators gleefully pointed out that “gnu” is another name for an antelope commonly known in South Africa as a wildebeest, or wild beast.

And indeed, this “wild beast” of a coalition has often seemed untamable.

Before the GNU, the ANC was used to making unilateral decisions, and the DA was used to loudly contesting those decisions from the rowdy opposition benches of Parliament. Mr. Steenhuisen once goaded the usually unflappable Mr. Ramaphosa to the point that the president snapped at him to On another occasion, the DA leader : “You go from Mr. Talk-a-Lot to Dr. Do-little.”

Since the two men and their parties became partners, there have been almost weekly headlines warning of the coalition’s impending demise.

Case in point: Since joining the GNU, the DA has threatened to go to court over a number of ANC-sponsored bills, including one on education and another on health. The DA is currently challenging the ANC in court over a land reform bill also condemned by the Trump administration.

Many also thought the end of the GNU was imminent earlier this year when the DA rejected the national budget prepared by a finance minister from the ANC. The ANC’s furious Secretary-General Fikile Mbalula responded by urging the DA to “file the papers,” if it didn’t want to be in the coalition anymore. “In a divorce, you file the papers,” he said.

Yet in the end, the marriage remained intact. The budget finally passed, and Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana praised the parties for finding a way through.

“Negotiation, debate, and compromise, as we have seen unfold over the last weeks, has been a necessary, if sometimes painful, investment” in the new era of coalition politics, he said.

The coalition’s survival, however fragile, is a boon for South Africa’s democracy, says William Gumede, a scholar of South African politics and founder of the Democracy Works Foundation, a think tank. To him, the disagreements within the GNU are natural and positive – as long as the coalition finds ways to weather them. “People who would have been fighting each other must now govern [together] in the national interest,” he adds.

The middle ground

For both parties, serving the national interest has meant moving toward the political center, says David Everatt, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand School of Governance in Johannesburg.

Mr. Ramaphosa has resisted pressure from those in his party who preferred to join forces with Mr. Malema and other Black populist leaders instead of a “white party.” And for its part, the DA has tried to demonstrate it has the interests of all South Africans at heart, as most of its voters are not white.

“I think [the coalition] has shown that the middle ground is far more attractive than the extremes for most South Africans, and certainly for the market,” Dr. Everatt says.

Indeed, after the GNU was formed, the South African rand strengthened, long-term interest rates fell, and , according to experts.

“For the first time, we are seeing government moving [with] more urgency,” says Mr. Gumede. This “wasn’t the case with the ANC because it had been in power for so long. ... They could just say, ‘Well, no matter what we do, Black people will vote for us.’”

Meanwhile, one published in April found that 60% of South Africans think the GNU is performing better than the previous ANC-only government.

Lonwabo Mati, a Black student in his late 20s, says he is pleased with the coalition’s work so far.

“Because of the ANC’s lack of majority ... they have to also appeal to the various members of the GNU to find consensus,” says Mr. Mati as he sits in a café in Johannesburg on a recent afternoon. “That’s a big plus for me.”

As the coalition approaches the first anniversary of its formation June 14, a new battle is shaping up over the ANC’s affirmative action policy. Known as Black Economic Empowerment, this is the policy that South Africa-born billionaire Elon Musk claims prevents him from bringing his Starlink satellite services to the country. The DA would like to see BEE scrapped.

Also having a coffee at the same Johannesburg café as Mr. Mati is Clint Payne, a white consultant in his 50s. With his Staffordshire bull terrier sitting beside him, he sums up his views of the GNU this way: “It’s better than the alternative, but less than the ideal.”